For our 350th episode, we looked at the history of the construction of the World Trade Center. After reading this article, listen to the show for a deeper dive into the story:

Let me take you back to a simpler time, back to a time where it might have been okay to hate the actual World Trade Center.

The World Trade Center was originally seen as a representation of New York’s own dreams and failures. The buildings represented progress to some, disruption to others.

An entire business district — Radio Row — was eliminated in its construction. Another neighborhood — Battery Park City — sprang up in its shadow. The monumental design by Minoru Yamasaki radically altered (distorted?) the skyline. Some of New York’s oldest streets were now blocked from sunlight. On the other hand, an area of Manhattan that would have been susceptible to rising blight was now renewed.

It was the apotheosis of post-modern design, the apex of New York City construction.

Everything grand and intolerable about New York City in the late 1960s/early 1970s was embodied here in these two impossibly tall shafts of metal.

Many saw a waste of resources and state governments with skewered priorities. Business interests were hopeful the buildings would reinvigorate the Financial District. They would, eventually.

But back in 1973 many openly wondered how its owner, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, were even going to attract tenants.

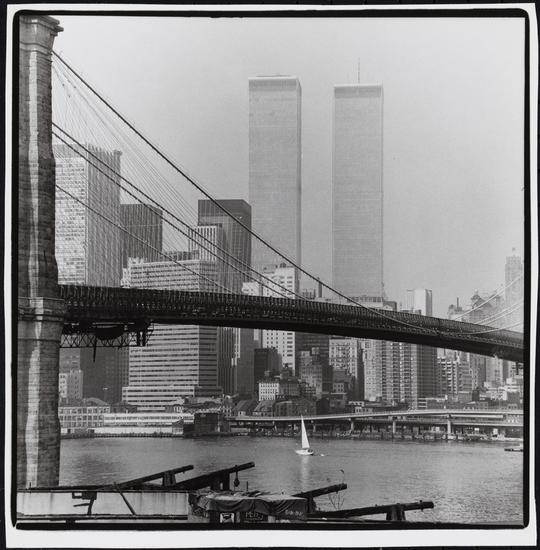

Below: The view of downtown Manhattan from a New Jersey marina

After years of construction that transformed lower Manhattan, the buildings were officially opened in a ribbon-cutting ceremony on April 4, 1973. Far from a rapturous embrace, the opening of the world’s tallest buildings was met with relief, resignation and turmoil.

Few were in a mood to celebrate two shiny new symbols of wealth in a city slowly nearing bankruptcy.

Here are a few more details from its opening day and its aftermath:

People were already over it: The opening was occasioned by severe rain. (It’s in good company; the opening of the Statue of Liberty was also met with a downpour.) Even without it, however, the celebration would have been heavily muted.

The ground was broken on the World Trade Center site almost seven years before, and New Yorkers had plenty of time to get used to the rising towers. The first tower had been completed by 1970, but by then, the city had become rather jaded to the expensive buildings. As it was, lower levels of the second building were still not even completed.

Disagreements: The top luminaries at the opening were New York governor Nelson Rockefeller and New Jersey governor William T. Cahill. The World Trade Center was a Port Authority project; PATH trains to New Jersey were rumbling underneath (or were supposed to be, see below).

While the two governors seemed in playful spirits, Cahill openly resented the backseat his state took in the finished product. According to author Eric Darton: “Cahill implies that New Jersey’s commuter rail needs have taken second place to the trade center, and Rockefeller, still grinning, points towards the Jersey shore. ‘You see all those magnificent container ports,’ he says, ‘that took all those jobs away from New York.’ “

In Absentia: Gone were the days when U.S. presidents showed up at the opening of New York landmarks, but President Richard Nixon did send a statement, hailing WTC as “a major factor for the expansion of the nation’s international trade.” That very same month, the Watergate cover-up erupted into the scandal that would eventually lead to his resignation the following year.

STRIKE! Not only was Nixon not there, but the man he designated to read the speech — Peter J. Brennan — was not even there. Three days earlier, the Brotherhood of Railway Carmen union began a strike against Port Authority. Because of the strike, the PATH train — that glorious feature of the new World Trade Center — was closed for a total of 63 days. Brennan was Nixon’s new Secretary of Labor, so it would hardly seem proper to break the picket line. Nixon’s speech was delivered instead by a Port Authority chairman.

Critics, Part One: Noted labor leader and powerful mediator Theodore W. Kheel was violently against the states’ interest in the World Trade Center. Calling it “socialism at its worst,” he demanded the governors take the podium on ribbon-cutting day and sell the building to private investors “at the earliest possible date.”

Others were perhaps understandably concerned that the buildings, given special tax status, were now a quarter-filled with state offices and certainly destined to empty and bankrupt office buildings with no such tax breaks in the surrounding area. Luckily, Kheel did live to see the building sold to private concerns in 1998.

Critics, Part Two: Somebody else was saving up some vitriol for opening day — noted architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable. Having years to craft some well-worded jabs, she did so in a column in the New York Times the following day. “These are big buildings, but they are not great architecture…..The Port Authority has built the ultimate Disneyland fairytale blockbuster. It is General Motors Gothic.”

Critics, Part Three: Labor leaders were disgruntled. Critics dismissed it. But many New Yorkers outright loathed it. It’s a bit disturbing to read such outright disgust over structures that we have very different feelings about today. From the Village Voice a week after the opening:

“The ecology-minded and those who are concerned with the energy crisis are fond of predicting that the building will have to be torn down — or at the very least abandoned — on that not-to-distant day when the power it consumes puts an intolerable strain on our already-diminishing power reserves.”

Nowhere to Eat: The World Trade Center could facilitate thousands of employees, but, on opening day, it had one restaurant, called “Eat and Drink,” where “the waitresses wear hard hats and its busboys wear vests inscribed “Ecologist” on the back.”

In the second building, a makeshift sandwich shop opened on the unfinished 44th floor. Needless to say, outside food vendors in the area were not displeased.

Subversion The ribbon-cutting ceremony also marked the end of One World Trade Center’s dominance as the world’s tallest building. Chicago trumped it when Sears Tower topped out at 1,454-feet less than one month later.

In New York, the buildings quickly became a totem of excess, of something that could be symbolically overcome. You may be familiar with the daredevil Philippe Petit and his insane and unbelievably majestic (and illegal) tightrope walk between the towers. But you may not remember that it took place just sixteen months after the opening, on August 6, 1974.

Two years later, King Kong performed a similar sort of feat in the 1976 remake starring Jessica Lange.

But there was magic in the air. On the very same day as the ribbon-cutting, in a hospital across the water in Brooklyn, a woman went into labor and gave birth to a child who would later become the nightclub-loving illusionist David Blaine. The World Trade Center and David Blaine — born on the same day!

Photography on this page, from various periods, by Edmund V. Gillon, courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York. Check out their online gallery for some more beautiful black-and-white shots.

This article originally ran on September 11, 2014.

2 replies on “The grand opening of the World Trade Center on April 4, 1973; Richard Nixon, labor strikes and “General Motors Gothic””

NOTHING breaks my heart more than any pictures of the towers. God, unthinkable. Bob

1. Your link to the 2014 post doesn’t work.

2. I certainly hope it’s still okay to hate the original WTC, because I sure as heck did then and do even more now. It really screwed with the wind all over Lower Manhattan. I went to school in Lower Manhattan! My mother worked there, at the AMEX, I spent a lot of time there. That wind was just wild, and I can only imagine nobody bothered to do any wind tunnel tests before they built the thing. Every time I go to the area now and I can walk around and my hair doesn’t get all messed up, I tell the kids, it was not like this.