Write that man a ticket! This rebel might have had a different cause had he been at yesterday’s New York city council meeting.

Write that man a ticket! This rebel might have had a different cause had he been at yesterday’s New York city council meeting.

Mark Twain, Humphrey Bogart and Fiorello La Guardia must surely be rolling in their graves today. This represents the most far-reaching ban on smoking that New York gentlemen have ever had to face.

New York ladies who smoke, on the other hand, have been down this path before. In fact, the new ban caps a period of roughly over 100 years of public smoking freedoms. Women who light up have been punished for it before.

Men have been legally allowed to smoke mostly where they like for much of the city’s history, and anybody who tried to stop them was met with resistance. Director-general Williem Kieft tried to outlaw the practice in New Amsterdam in the 1640s. As Washington Irving once colorfully described it: “He began forthwith to rail at tobacco as a noxious, nauseous weed, filthy in all its uses; and as to smoking, he denounced it as a heavy tax upon the public pocket, a vast consumer of time, a great encourager of idleness, and a deadly bane to the prosperity and morals of the people.” But nobody was going to give up their tobacco, and Kieft backed off.

Smoking was a sign of prosperity in Gilded Age New York, the most common activity within the corridors of New York’s finest social clubs. Public transport was off limits, of course, but that didn’t stop everybody. (Lighting up a cigar in a streetcar, for instance, would earn you a hefty fine.) Posh restaurants in the late 19th century often required men to smoke in separate rooms. But with the rise of lobster palaces like Rector’s — rollicking, casual restaurants with a festive atmosphere — older restaurants like Delmonico’s had to loosen their policies.

Eventually men were allowed to smoke in the dining rooms. And sometimes, women would light up too, though such flagrant social rebellion was often met with polite shock. Places like the Plaza Hotel and Delmonico’s would put folding screens in front of tables that sat such bold women. It wasn’t the smoke itself that scandalized patrons. It was the sight of ladies enjoying such a male pastime. (Perhaps they should have done more; at least two members of the Delmonico clan died of smoking related illnesses.)

The sight of a woman enjoying a good cigarette flew in the face of proper etiquette, thus becoming a handy display of rebellion in a age when women were fighting for other rights, most notably the right to vote. From Meta Lander’s 1888 book-length tirade called ‘The Tobacco Problem’ :”On a crowded boat, between New York and Boston, a lady (?) passenger, unable to sleep, rose at three, virtuously mended her gloves, and then, O shade of Minerva! leaning back in her arm-chair, gave herself up to a cigarette; while, stretched on mattresses around her, many looked on with undisguised amazement and disgust.”

The sight of a woman enjoying a good cigarette flew in the face of proper etiquette, thus becoming a handy display of rebellion in a age when women were fighting for other rights, most notably the right to vote. From Meta Lander’s 1888 book-length tirade called ‘The Tobacco Problem’ :”On a crowded boat, between New York and Boston, a lady (?) passenger, unable to sleep, rose at three, virtuously mended her gloves, and then, O shade of Minerva! leaning back in her arm-chair, gave herself up to a cigarette; while, stretched on mattresses around her, many looked on with undisguised amazement and disgust.”

Indecent? Or independence? The debate came to a head in 1908 when, for two weeks at least, it was actually illegal for women to smoke in public. ‘NO PUBLIC SMOKING BY WOMEN NOW’ read the New York Times on January 21, 1908. “Will the Ladies Rebel? As the Ladies of New Amsterdam Did When Peter Stuyvesant Ordered Them To Wear Broad Flounces?”

The mayor, George McClellan, quickly revoked the unpopular law. Twelve years later, women would have the right to vote and the freedom to smoke. (But not to raise a toast; alcohol was prohibited by 1920.)

This new law seriously undermines decades of accomplishments by beatniks, poets, film noir icons, jazz musicians and gang members who have worked tirelessly to make smoking cool.** James Dean, we have betrayed you!

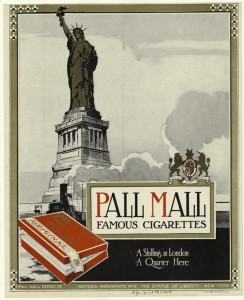

Above: a 1914 Pall Mall advetisement, using Lady Liberty to exemplify the American freedoms that smoking brings!

**Of course, many of them died of lung cancer.