The old port at night was no place to be.

Weathered taverns and boardinghouses sit next to uninhabited warehouses, separated by dimly lit South Street from the shadow of rocking masts and creaking piers that sank into the black water of the East River.

A lonely sailor, soused from the wares of the cheapest Water Street saloon, stumbles down the cobblestone. A figure emerges from the corner. A whistle. Another man steps from behind. And the lonely sailor has vanished.

The fear of ‘disappearing’ in New York kept many awake at night in the 19th century. In a world where everybody was essentially ‘unplugged’ and ‘off the grid’, there was a sense that people could simply vanish, almost as if absorbed into the urban environment without a trace.

Moral crusaders, in a tirade against personal independence, warned parents to keep close watch on their daughters for fear they would be snatched from the street, plied against their will with opium and turned into prostitutes.

Some thought this might have been the fate of ‘cigar girl’ Mary Rogers back in 1841. And as late as 1911, some speculated this was the fate of the socialite Dorothy Arnold, one of the most prominent disappearances of the Gilded Age. [Hear more about her story in our podcast from last May.)

But it was men who were often the victims of street kidnapping. The transient nature of the New York port world mixed with the influx of new immigrants — many of them younger men — fostered a disturbing cottage industry of so-called impressment (or ‘shanghaing’ in the old vernacular), where drunken men were either forcibly taken off the street or taken advantage of in their inebriated state and put to work on a sailing ship.

In 1870, a sailor ‘under the influence of liquor’ was tied up and dragged onto a boat. A Fort Hamilton soldier in 1882 was kidnapped and placed aboard a ship off Staten Island. While his message, thrown overboard in a bottle, was received, officials were unable to rescue him as the boat sailed for its destination: Hamburg, Germany.

Below: The forest of masts along South Street, 1890

It’s impossible to know exactly how many men were forced onto boats along New York’s port, as the victims were frequently drunk, thrown onto boats that embarked on long voyages and then failed to press charges when they returned. An article in 1910 claims that ‘[h]undreds of sailors were captured [in New York Harbor], usually in the saloons, beaten into insensibility, to awake when the ship was at sea and the Captain an absolute tyrant.”

There would be an actual, near legal version of shanghaiing called crimping where the sailors, still taken at will, would be forced to sign an agreement, paid for their services but not allowed to leave. They would embark on often long voyages, and by the time they got back, “his anger is likely to have died out.”

By the late 1910s, federal laws protected the rights of seamen, and most shanghaiing and crimping practices were abolished. Except, of course, for those in illegal industries, and especially a brand new one created by the advent of Prohibition in 1920.

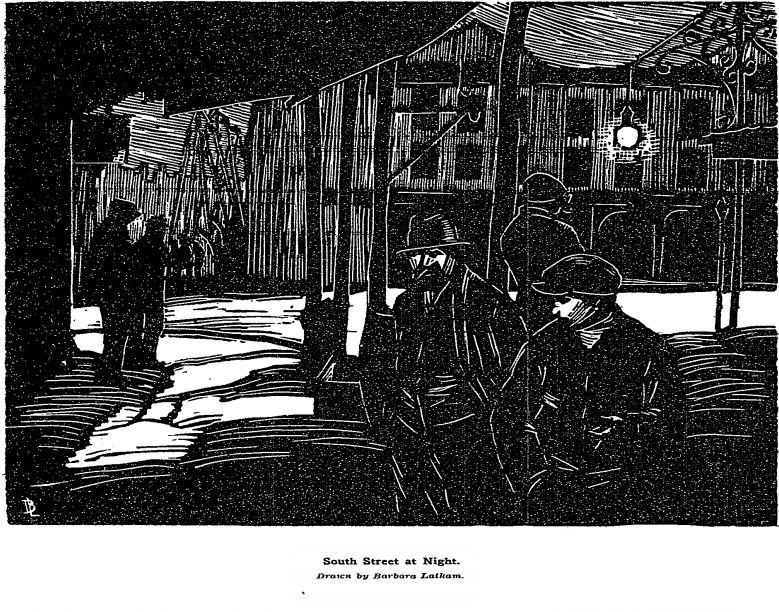

This type of kidnapping was perhaps the most frightening of all. “South Street Whispers of Shanghaing” announced a rather in-depth New York Times article in 1925. Now, instead of ‘crimps’, who lurked in sailor’s boarding houses, looking for possible captives, it was whole ‘shanghai gangs’ that ruled the shadows of the seaport.

“I have been drugged and held captive on a ship,” claimed one note found in a bottle and mailed to the police. An anonymous shipping master reported hearing of a victim “drugged in one of these newfangled speakeasies that are run as drug stores. They said along the street that a shanghai gang had got him, stole his money and shipped him to sea….The man is gone, and who can trace him?”

Below: South Street in 1920 in a snowstorm during the first year of Prohibition (Courtesy Flickr/wavz13)

The destination for these unlucky men wasn’t a long-distance voyage but rather a line of near-invisible vessels permanently moored off the American coast. ‘Rum Row‘ facilitated the distribution of alcohol into the United States, with product passing to smaller boats and shady, midnight deals made between mobsters and smugglers. It was an unpleasant and dangerous job, constantly under the fear of capture, betrayal and accident. In an illegal industry with few rules, unwilling men could be discarded.

This also made Prohibition-era impressment a mystery and something of an urban legend. How much forced capture really went on? The Times report interviews several sailors and even a salty South Street bartender, but their names are kept out of the story. Two men, thrown aboard a Rum Row schooner, “were made to work, starve and suffer for water, under threats,” only escaping when the vessel was captured by authorities.

South Street’s changing fortunes may have prevented a widespread problem of the sort which occurred in the 19th century. Â The old pubs and grog houses were closed or turned to speakeasies, and heavy shipping had moved on to other ports throughout the harbor, on the Hudson River side, and in Brooklyn and New Jersey. The ports themselves were heavily controlled by mob bosses — and the promise of mob money — which perhaps made such forced recruitment unnecessary. And of course the success of illegal Prohibition industries relied on knowing which laws to abide and which to skirt.

Yet the fear of vanishing kept men on their toes at night as they passed through the neighborhood, keeping in the light as they stumbled down South Street.

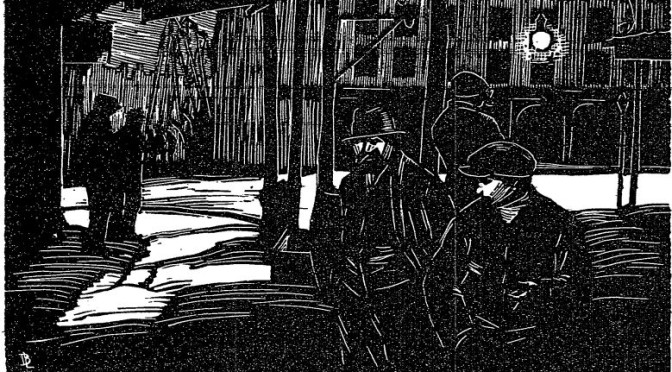

At top: Drawing by Barbara Latham courtesy New York Times.  It accompanied the article mentioned above.