The Fortress of Fifth Avenue: the Murray Hill Reservoir

We share a lot of the same needs as New Yorkers of the past, but we’ve just gotten better at hiding the unpleasant ones. There are a great many mental institutions and specialized medical facilities in the city; they just aren’t in creepy, old Gothic buildings anymore. Prisons are out on islands or in nondescript beige towers flaunting only the barest hint of iron bars. We don’t dress them up in Egyptian morbidity like the famous Tombs prison of Five Points.

Our trains and our electricity reside underground, and so does our water, mostly. There are only a few places that seem to suggest that New York City’s water supply doesn’t just magically appear. Water towers dot the skyline, recalling romantic comic book landscapes, while water treatment plants, spread mostly through the outer boroughs, obviously do not. Then there are the reservoirs, the grandest of these, the Jerome Park Reservoir in the Bronx, is a landmarked structure of enormous, albeit hidden, beauty. It’s currently drained and sitting like the Earth’s largest off-season swimming pool.

But New Yorkers used to live with their water, contained in reservoirs meant to evoke might, sophistication and security. After all, New York only got fresh water from the Croton Aqueduct in 1842; before that, it was mostly obtained from wells, cisterns, and that nasty old Collect Pond. People were proud of their new water system, so why not show it off?

Here’s a gallery of New York’s old 19th century reservoirs. In tomorrow’s podcast, we’ll elaborate on the marvelous story on how the city got its water:

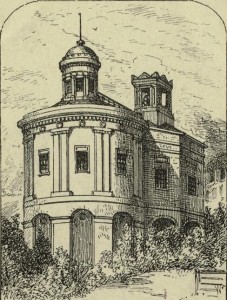

The Manhattan Company reservoir on Chambers Street was opened in 1801 and was quickly deemed inadequate. Looks lovely though. If it were still around — it was demolished in the early 1900’s — it would probably be a nightclub today.

13th Street Reservoir: Opened in 1830 as a water-pooling resource for fire fighting, it pumped water to hydrants on Broadway, the Bowery and other streets, but was little help in stopping the blazes of the Great Fire of 1835.

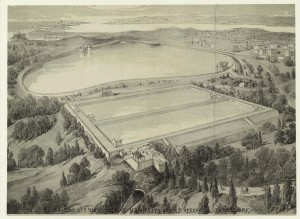

The Yorkville reservoir, how it looked on its opening in 1842. It was located between 79th and 86th Streets and between Sixth and Seventh Avenues. Many years later, was surrounded by Central Park and was later torn down to become the park’s Great Lawn. What does remain, however, is….

…the Central Park receiving reservoir, built in the 1850s and, unlike the Yorkville, incorporated into the park’s designs. Today it’s named for Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who lived nearby and frequently jogged around it.

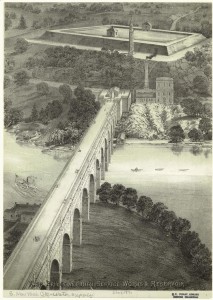

The spectacular High Bridge, part of the Croton system, with its adjoining smaller reservoir and water tower, serving the needs of residents of Manhattan’s higher elevations.

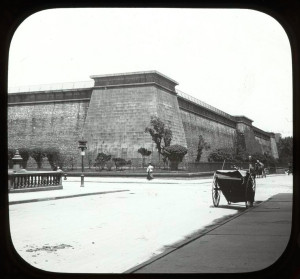

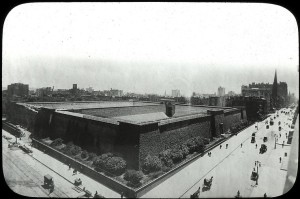

The grand Murray Hill Reservoir, probably the most popular of the reservoirs with 19th century tourists. Situated on land that had held the fabulous Crystal Palace (destroyed by fire in 1858), the reservoir was demolished in the 1890s to make room for Bryant Park and the New York Public Library.

Brooklyn was maintained in the 19th century in two reservoirs, one in Ridgewood and the other high atop Mount Prospect, although the ultimate source of the water came from a variety of places.

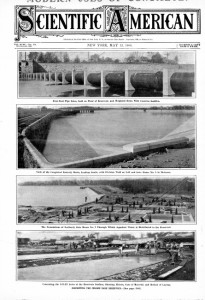

An issue of Scientific American in 1906, celebrating ‘the concreting’ of the Bronx’s Jerome Park Reservoir which opened that year and contained portions of both the old and new Croton Aqueduct systems.

The 1917 Silver Lake reservoir in Staten Island was constructed, like the Central Park reservoir, to be a functional feature of a park setting.

Pictures courtesy the New York Public Library, the Brooklyn Museum and the Library of Congress. Thanks as always to these institutions. The Scientific American can be found here.

3 replies on “The art of the reservoir, New York’s forgotten architecture”

You mentioned the Ridgewood and Mount Prospect Reservoirs as being part of Brooklyn’s system. It was my understanding, that reservoirs in Valley Streem, Hempstead, Wantagh & Massapequa wre the ultimate sources of Brooklyn’s water. Two of those reservoirs would eventually become state parks after the incorporation of NYC. I recall reading a story once that the Ridgewood Reservoir lost more water than what was distributed due to the geology of its location.

Kevin

Yes, those were also sources for Brooklyn water. The Ridgewood sourced its water from Hempstead, Jamaica (Baisley Pond) and other places. Water from Mount Prospect was pumped from Ridgewood.

Cool post but what about Queens?