A passenger steamer passes along the Hudson, early 1900s. (Courtesy LOC)

As a kick-off to the Bowery Boys Book of the Month section, I thought I’d ask Mark Siegel, the author of “Sailor Twain or The Mermaid in the Hudson,” a few questions on his inspiration for the graphic novel. I was especially interested in the origin of the book-within-a-book, as it seemed like something familiar….

So which inspiration came first, a history-based story set on the Hudson or a love story involving a mermaid?

It’s hard to say, because the Hudson River and the mermaid have been inseparable in my mind for the nine years I was working on the book. But the compulsion of a siren’s song was the initial spark—these things in life that compel us and override our reason and our common sense, things we would follow . . . down, down, down.

The 1887 setting revealed itself very early. There’s the romance of the Gilded Age, but also the cross currents of that time which I found irresistible: the industrial revolution waxing and the scientific mind in ascendance, the women’s suffrage movement, the uphill fight for Black people’s rights, the lingering shadows of the Civil War, and with poetry and literature, a search for a new and unique American myth and magic—from Irving to Twain to Whitman to Emily Dickinson… Such rich soil to plant a story’s seeds in. But yes, the seed itself is a love story, or rather three interwoven love stories.

Why did you decide to name the captain Twain? The story makes a couple clever allusions to Mark Twain then launches into a genre quite unlike a Twain story. Is the randy Lafayette an allusion to a real life character as well (say Marquis de Lafayette perhaps)?

With every major character in Sailor Twain I was interested in finding a resonance in the American psyche. Lafayette evokes the Marquis of course; a great emblem of France, and in the love-hate relationship between France and the United States, that name belongs on the love side: a France that embraces the American ideal. Now at first, the Lafayette in our story seems like a cliché of the lecherous Latin man, but then his destiny takes him someplace beyond that.

Twain is a dangerous name to give a protagonist—it’s such a trademark of that Samuel Clemens fellow. And Captain Twain even resents being asked if he’s related to the writer! He grumbles “That’s not his real name, you know…” But that’s only the starting point. Sailor Twain also plays with the Doppelganger theme—so splits or “twainings” of all kinds: in the Captain, the passengers, the recent Blue and Grey Coats of the Civil War, even in the mighty Hudson herself. The Algonquian name for the Hudson was “The River That Flows Two Ways.” So the name Twain runs throughout every level of the story. Early on in the making of it, it couldn’t be any other name for our doomed captain.

At the core of the graphic novel is a mysterious book ‘Secrets & Mysteries of the River Hudson’ written by the equally mysterious C.G. Beaverton. There’s something very vaguely familiar about this book, perhaps like something similar I’ve read doing research. Is it based on a real book?

Oh good! I hoped for exactly that sort of vague familiar feeling. I wrote out most of that book within the book, so I could know it myself. It’s like some travelogues, but also the mystical searches of Graham Hancock like in his The Sign and the Seal—part rigorous history, part guidebook, part fable and mystery-dream. Leonardo DaVinci‘s travel journals were oddly enough an early inspiration: they’re mostly very detailed, very exact and truthful, and suddenly he talks about visiting foreign lands and seeing giants and impossible creatures and all kinds of baffling things. I love that.

How the Beaverton book evolved though, is the author became more of a story-collector than a visionary—something like Zora Neal Hurston, or the folk-song collectors in the Appalachian mountains. Some of the Beaverton stories draw from actual Hudson folklore, and from all real places—plus some of my own strange visions in some of these places.

Your artistic style also seems inspired by old photographs, not just in the use of ink but in the framing of certain scenes (on the waterfront or in Central Park, for instance). What was your research process with ‘Sailor Twain’ and did any old archival photos or books inspire the direction of the story?

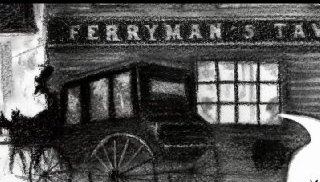

I collected thousands of pictures from all up and down the Hudson, indoors and outdoors, fashions, carriages, ship menus and timetables, anything I could get my hands on. Lots online—imagine my joy when I first came across The Bowery Boys, which I have plundered shamelessly—but also many hours spent in New York historical societies, at the great NYHS itself, and the NY Public Library, for archival prints, 1880s newspapers and old maps especially.

In a few instances I would draw directly from a photograph, or an engraving from Harper’s Weekly (“The Journal of Civilization”!) but more often than not, I “digested” the pictures and let them evolve in my imagination before drawing the finished pages of Sailor Twain.

Occasionally, some face in an old daguerreotype would strike me deeply, a beautiful face, or a mournful pair of eyes, and I would bring that person into the story, if only in the background. But I don’t think the story really took its cues from archival photos; everything I found seemed pressed into the service of the story, rather than the other way around.

The art has a mix of Gothic and impressionistic elements, with a few dips into the playful. (Lafayette, that nose! Twain, those eyes!) How did you settle upon the haunting, mystical tone of the images?

There’s something I love about comics, something they can do which movies can’t too easily: mixing styles in different registers, blending for instance realistic characters with more cartoon-y ones. Since I worked in charcoals, everything was unified by the shading; but within the smoky, smudgy, steamy atmosphere of it, there are some characters who are very naturalistic, others very iconic, almost geometric, like Captain Twain himself. The mermaid, oddly, looks much more realistic than he is.

I was hoping for a mystical, haunting mood for the Hudson in this very stormy summer of 1887… Again the magic of charcoal lent a fog-shrouded quality, a bit like classical Chinese painting, where things appear and disappear in the mist…

And I enjoyed sabotaging some of the more serious moments with humor. Like in an early dramatic plot point, when the Captain finds a wounded mermaid, bleeding on his deck one night, and tries to pick her up—as it turns out, she is quite slimy and slippery and she slips through his arms and bonks her head on the floor. Talk about killing the romantic buzz. I like being able to go playful, then serious again, visually and narratively.

Storm King Mountain, circa 1890, from a photograph by William Henry Jackson (courtesy LOC)

Mermaids may not actually be living in the Hudson, but there are plenty of other urban legends associated with the Hudson River Valley. Any that are your particular favorite?

Mermaids may not be living in the Hudson, you say… But treacherous currents alone can’t account for all the shipwrecks at World’s End, just south of West Point Academy!

But you’re right, there are so many great legends up and down the Hudson River Valley… The stories about Spuyten Duyvil; the supposed origin of the term “cocktails” in an Elmsford tavern where drinks were served with a cock’s feather in them (not true, I am told); the ghosts and various spirits attached to some of the Hudson mountains, like Storm King and Anthony’s Nose; of course I have a soft spot for Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle… I also like the one about Henry Hudson and the Catskill Gnomes.