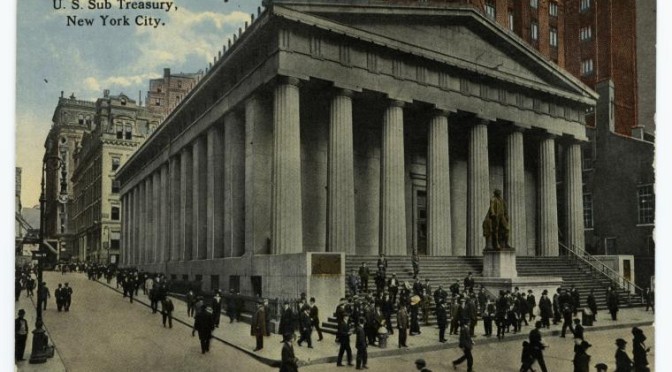

The U.S. Sub Treasury Building — today’s Federal Hall — as it appeared in a colorized postcard in the 1900s (courtesy NYPL)

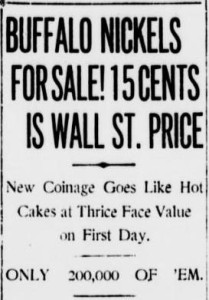

“Hey! Getcha buffalo nickels here. Only 15 cents!”

On March 1, 1913, the usual bustle of Wall Street was enlivened with the voices of young men — mostly messenger boys, bank runners and peddlers, according the Evening World — with handfuls of shiny new nickels, the first run of what would become known as the Indian Head nickel or the Buffalo nickel. And in these heady morning hours, many managed to sell the five-cent piece for triple its value.

“The down-at-the-heels men, who sell picture postcards and neckties from pushcarts on Ann Street, scented a bargain and hurried to the Pine Street El Dorado to sink their little capital in nickels.” The “Pine Street El Dorado” in that quote refers the New York Sub Treasury building, later referred to as Federal Hall. (It’s second entrance is on Pine Street.) The Sub Treasury received $10,000 worth of new nickels in ten wooden kegs.

Unfortunately for these budding young nickel entrepreneurs, the novelty wore off by noon and the Buffalo nickel sunk back down to its original face-value cost.

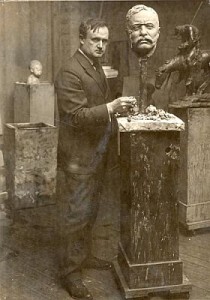

The new nickels were designed by the sculptor James Earle Fraser, a former assistant of the estimable Augustus Saint-Gaudens and best known in New York perhaps for his equestrian statue of Theodore Roosevelt outside the American Museum of Natural History.

Fraser, a professor at the Art Students League, designed the new coin from a studio at 3 MacDougal Alley, off of Washington Square Park. An admirer of Western and Native American imagery, Fraser used a series of models for the noble Indian profile on the front of the coin. For the buffalo on the reverse side, Fraser reportedly went to Central Park Zoo and used their old buffalo Black Diamond for a model.

At right: James Earle Fraser in 1912 with a clay model of a Theodore Roosevelt bust (courtesy National Cowboy Museum)

Or at least, Black Diamond has always been considered the model for the buffalo nickel. In fact, Fraser may also have used specimens from the Bronx Zoo including a fiesty beast named, appropriately, Bronx. Given the renown of the Bronx Zoo collection — the institution essentially saved the buffalo from extinction — it might have made more sense to use their animals as models.

Despite outcries from manufacturers of coin operated devices — who claimed the new five-cent piece would not fit in their machines — the buffalo nickel was minted in February 1913, replacing the Liberty Head nickel that year. (A small handful of Liberty Heads were made in 1913, becoming some of the most prized coinage among the numismatic set.) Americans got a preview of the new coin when a small number were distributed by President William Howard Taft at the groundbreaking for the National American Indian Memorial in Staten Island, a monument that was ultimately never built.

Despite outcries from manufacturers of coin operated devices — who claimed the new five-cent piece would not fit in their machines — the buffalo nickel was minted in February 1913, replacing the Liberty Head nickel that year. (A small handful of Liberty Heads were made in 1913, becoming some of the most prized coinage among the numismatic set.) Americans got a preview of the new coin when a small number were distributed by President William Howard Taft at the groundbreaking for the National American Indian Memorial in Staten Island, a monument that was ultimately never built.

A week later, on the first day of March, rolls of the new buffalo nickels were distributed to New Yorkers on Wall Street, and millions more sent across the country for distribution.

Perhaps Fraser’s design was a tad too whimsical for some. The term ‘buffalo nickel’ soon became slang for something nearly worthless. Just a month later, the New York Sun reported, “[T]he $1,500 mathematical job didn’t mean anymore to him yesterday afternoon than a buffalo nickel.”

In 1921, one of Fraser’s human models, the chieftain Two Guns White Calf, pitched his teepee atop the luxury Hotel Commodore next door to Grand Central Terminal in a publicity stunt.

The buffalo nickel was replaced in 1938 by the more familiar Thomas Jefferson model.

Below: A news clipping featuring an image of Two Guns White Calf with his daughter. (Courtesy Flickr/sharknose)

Coin image courtesy Coin Collecting For Beginners

1 reply on “Fun money: The Buffalo nickel, 100 years old this month, makes Wall Street messenger boys rich (for a couple hours)”

Seeing as how the Buffalo Bills are my favorite team, I would love having a coin like that!

-Rich