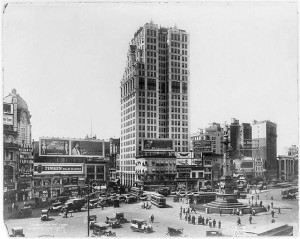

Columbus Circle in 1921, looking west. Healy’s was a few blocks north of this scene.

Many of New York’s most popular restaurants and cafes a century ago were located around Columbus Circle, lively hot spots that drew in the theater and burlesque patrons well into the late hours. Crowds would exit the Park Theater and head over to Reisenweber’s Cafe to take in some champagne and cabaret, years before it would be associated with bawdy star Sophie Tucker. Others might partake of the beefsteak at the Morgue on West 58th Street or Child’s Restaurant a block over.

One of the busiest spots was Healy’s (slightly north, at Broadway and 66th Street), a spacious dining and dancing spot, featuring an indoor ice-skating rink and enormous ballroom, among its many indulgences. It was one of New York’s most trendy dining palaces in 1913, the site of a celebratory dinner by artists from the Armory Show just a few months before.

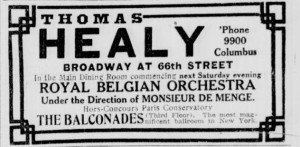

Below: An advertisement for Healy’s from 1914

But nobody was exactly celebrating at 1 a.m. on August 13, 1913, when the police burst into Healy’s and violently threw out all the patrons. Men were grabbed by their collars and thrown to the sidewalk. Women screamed as they were separated from their tables, “shoved, pushed and dragged” to the doorway. Thousands of people had gathered outside, both curious and perturbed, shouting at the police and cheering on the discarded diners.

The drama made the front page of every newspaper the next morning. “Diners Thrown From Healy’s,” said the Sun. “Many Are Dragged Away Carrying Dishes and Table Cloths.”

So what was the problem exactly? Naturally, it had to do with liquor.

The fun began several days before, when Mayor William J. Gaynor instigated a new ‘cafe curfew’ for the wild lobster palaces and nightclubs that were turning Midtown into an all-night soiree. Establishments holding proper liquor licenses must now close at 1 a.m. unless granted an exemption or extended license (often given to hotels).

This did not make Broadway proprietors happy, as it greatly cut into profits. However most restaurant and cafe owners along the “White Light zone“ planned to comply with the order, fearing fines or police reprisals.

But Thomas Healy was ready to fight the law. His lavish cafe at Broadway and 66th Street thrived on the after-theater, late-supper crowd, a party crew who liked their champagne. Although Healy’s regularly closed at 2 a.m., that one lost hour would have greatly hurt business, Healy claimed.

He also contested the wording of the law. It stated that “any room which liquor is sold during lawful hours must be closed and the doors locked during the prescribed hours, whether for the sale of liquor and foods.” If his bar room was indeed locked up, why couldn’t his patrons stay and enjoy themselves in the dining room?

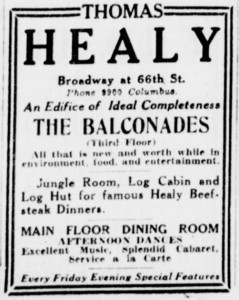

At left: An ad from 1915. Note the ‘Jungle Room, Log Cabin and Log Hut for famous Healy Beefsteak Dinner’

Healy stood ready to combat the mayor, keeping his place open while filing an injunction to keep the law at bay.

For several days, police entered the restaurant and asked patrons to leave at 1 a.m. On Tuesday, August 12, police barricaded patrons in the restaurant, announcing that none of them could leave until 6 a.m. But a defiant Healy removed his remaining diners out a back entrance, foiling the police.

This is certainly explains why the police were especially hostile the following day, August 13. At 1 a.m, police officers mounted the orchestra stage and announced that everybody must leave the restaurant. Drunken patrons laughed and even booed the officer, many proclaiming they had no interest in leaving. Most likely, it was this stubbornness that ignited the rough-handling that followed.

“The recalcitrant guests found themselves enfolded in the uniformed arms, lifted into the air, rushed down the disordered aisles and literally thrown into Columbus Avenue,” reported the New York Times. “In the scramble, tables went over, chairs were smashed, electroliers were damaged, glasses and crockery were broken into fragments. There was pandemonium for a time.”

Violence returned the following night, Thursday, August 14, as rebellious New Yorkers were now insolently dining past the allotted time. Promptly at 1 a.m., an increased force of fifty police officers rushed the restaurant. “Three hundred men and women were led, pushed, shoved, carried, clubbed and thrown out.” [source]

One of those patrons was New York District Attorney Charles S. Whitman (pictured above in 1910), a rumored candidate for mayor and one of the city’s most popular politicians. (In 1916, he would be elected governor of New York.) His appearance at Healy’s was clearly to draw attention. Thousands of people crowded the streets; the nearly elevated train station was filled with people trying to get a better look, and ‘automobile parties’ cruised by, desperate for a peek at the violence inside.

Whitman’s appearance had done the trick. Gaynor backed down, allowing Healy’s to remain open if it wished. In fact, warrants were then issued for police detective John. F. Dwyer and two dozen police officers.

But Healy had created a bit of an unwieldy beast. Crowds gathered the next night and cars lined the street, anticipating more excitement, building uncontrollable mess that the proprietor actually called the police himself! In the end, Healy did end up closing at 1 a.m., just for the protection of his own restaurant and staff.

5 replies on “The Incident at Healy’s: Wild nightlife in Columbus Circle, police brutality and spirited protests against ‘cafe curfew’”

That particular Charles Whitman (as opposed to one of more recent vintage, after whom a tower is unofficially named in Austin TX) is also the “Grandfather-in-law” of a more recent Governor, Christie Todd Whitman of New Jersey. (What is it about New Jersey, that they keep electing “Christie’s”?)

When reading this post, I couldn’t help but to think of the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969. That, too, began with a police raid, ostensibly over the establishment’s lack of a liquor license. Places that served homosexual patrons couldn’t get liquor or cabaret licenses, so they were operated (by the Mafia, some claim) as illegal saloons.

I mention this because the way liquor and cabaret license laws were enforced were never about controlling booze,dancing or music. They were a means of enforcing other kinds of social control, usually against some “undesirable element” of the population.

My maiden name is Healy,My father and grandparents were from New York and I am just curious if I am related to the Healy’s mentioned in this story…

Funny story… Dan Healy, Daniel Healy, husand of Boop Boop a Doop Girl Helen Kane owned the same exact Grill in the same exact place? And it was still called Healy’ s Grill. I wonder if it still exists today? Or is it gone forever?

During that time period my grandfather worked at this restaurant. I wonder if he was there that night.