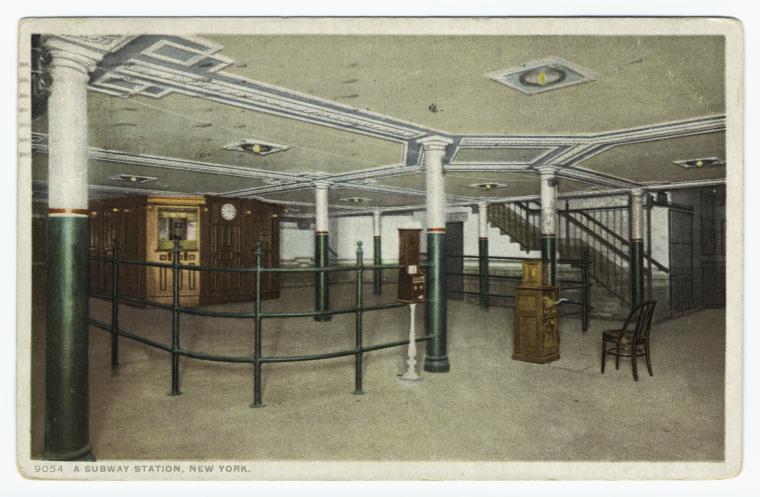

Above: Protect this station from the rueful blight of subway advertisements! (Pic NYPL)

There once was a time, believe it or not, when the city was so concerned for the aesthetic beauty of the subway that an early controversy broke regarding the scandalous inclusion of advertisements in subway stations.

There once was a time, believe it or not, when the city was so concerned for the aesthetic beauty of the subway that an early controversy broke regarding the scandalous inclusion of advertisements in subway stations.

The stations designed for those very first subway rides in 1904 were dictated by the guidelines of the City Beautiful movement, an early-century attempt by American cities to best the beauties of Europe and promote civility through architecture and urban design. Overseeing the process then was the Municipal Art Society, formed just ten years prior by Richard Morris Hunt and bolstered by rich patrons and grateful city involvement. (In fact, one of the Society’s first jobs was covering the ceiling of City Hall with an ornate mural.)

Keeping the subway so very ‘city beautiful’ was crucial to their plans, as the original route ran the length of Manhattan and would unify those tasteful civic ideals. So imagine the absolute mortification one day when a dignified Society member stepped down into a subway station to see a colorful advertisement for a corset.(Such as the 1904 advertisement above.)

Within days the opening of the first subway on October 27, 1904, private companies began descending into stations, hanging advertisements in crude frames upon the tile, in many cases damaging the freshly made walls. As standard paper materials and cheap tin framers were used, the ads quickly deteriorated, creating a drab and unappealing mess. “New York’s $35,000,000 subway, instead of looking like the immaculate place for which the city spent its money, is beginning to look like a billboard in need of the billposters,” claimed the New York Sun.

According to the Nov. 11, 1904, edition of the Tribune, a “peculiar clause” in the original IRT contract allowed for the company to allow “unobjectionable advertising” on the walls.

However, to the Municipal Art Society, no advertising was unobjectionable, and they threatened to sue the IRT. Â The governing body in the middle, the Rapid Transit Commission, was at first non-committal. They were urged to visit the ‘model’ subway station at 18th Street. (That station, on the 6 line today, is no longer in service.)

But the organization eventually relented on Nov. 22 by greatly limiting — but not entirely restricting — advertisements. Â William Barclay Parsons, the subway’s chief engineer, was even on hand to present the kind of advertising that would be permissible, displayed in an expensive frame “of copper, handsome and heavily finished. The back was of zinc.” In other words, a model way that would prove too expensive to mass produce. Also thrown out: slot machines and flower stands.

Public sentiment leaned towards approval of the commission’s decision. “It is pretty well established that the advertising signs in the Subway are condemned, and very properly condemned, by public opinion,” claimed a Times editorial.

Public sentiment leaned towards approval of the commission’s decision. “It is pretty well established that the advertising signs in the Subway are condemned, and very properly condemned, by public opinion,” claimed a Times editorial.

But the IRT believed it was in its rights to open the stations to paying advertisers. The night of the transit commission’s decision, in fact, an odd sort of rebellion occurred: subway stations were swarmed with workers “sent out to affix permanently to the station walls as many of the advertising placards as they could before they were stopped by injunction,” along the way drilling holes into the tile walls, causing hundreds of dollars worth of damage. Curiously, no police action was taken, and most IRT employees looked the other way.

This sent the aesthetes of the Municipal Art Society into a swoon! They petitioned the mayor to charge the IRT with damages — the subway was, after all, city property, although the IRT was franchised to operate it.

It would of course be a losing battle. A meeting of the Architectural League of New York the following month merely concluded that subway stations had been designed improperly and without the option for proper, tasteful advertisement. Â In the city’s glee to create a purely immaculate environment, they neglected to take into account the inevitability of public consumption and private corporate power.

With City Beautiful proponents realizing they had little legal standing, the IRT eventually won the battle to allow advertisements, and further, to authorize small independent businesses, “flower stands, slot machines, and the like” to return to the stations.

I do find it amusing that people in 1904 sarcastically referred to the framed advertisements as ‘art’ and the IRT as ‘curators of the subway art museum’. To highlight I reproduce for you a truly snarky editorial that was run in the November 5, 1904 issue of the Evening World:

“Alas! How can we ever hope to become a community of culture and refinement when art is thus strangled at its birth? The poster advertisers were rapidly uplifting us from vandalism to aestheticism. They were educating our sense of form and color, till we could thrill with the subtle beauties of a carmine corset upon a purple background, could palpitate with joy at the chiaroscuro of an ultramarine whiskey bottle against a gamboge sunset, could almost faint with ecstasy at the composition of lilac lingerie amid a sea-green cloud effect.

“Are beautiful works of art like this never to cast their lambent lustre from Subway walls?

“Alas! It seems as though in our Subway we shall have to lose the new and higher art which finds expression in corsets and whiskeys and patent medicines and content ourselves with crude white tiles and simple frescoes.

“It will be a sad blow to lovers of subterranean picturesqueness.”

Corset ad from Victoriana. Dr Kings from LOC. Target train from NYC The Blog.

An earlier version of this article was published here in 2010.