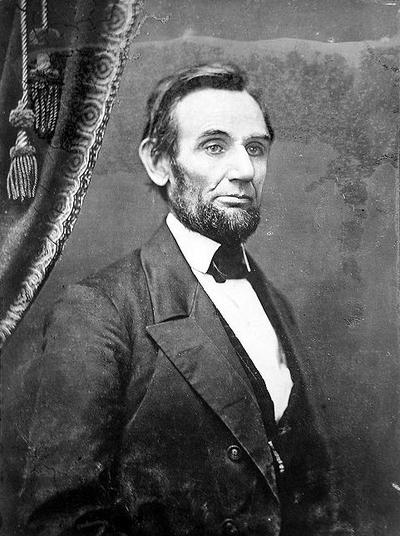

On April 15, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln died from his injuries by the assassin John Wilkes Booth who shot the president the previous evening at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

It was a fate promised to him by Southern sympathizers from the moment he was first elected on November 6, 1860.

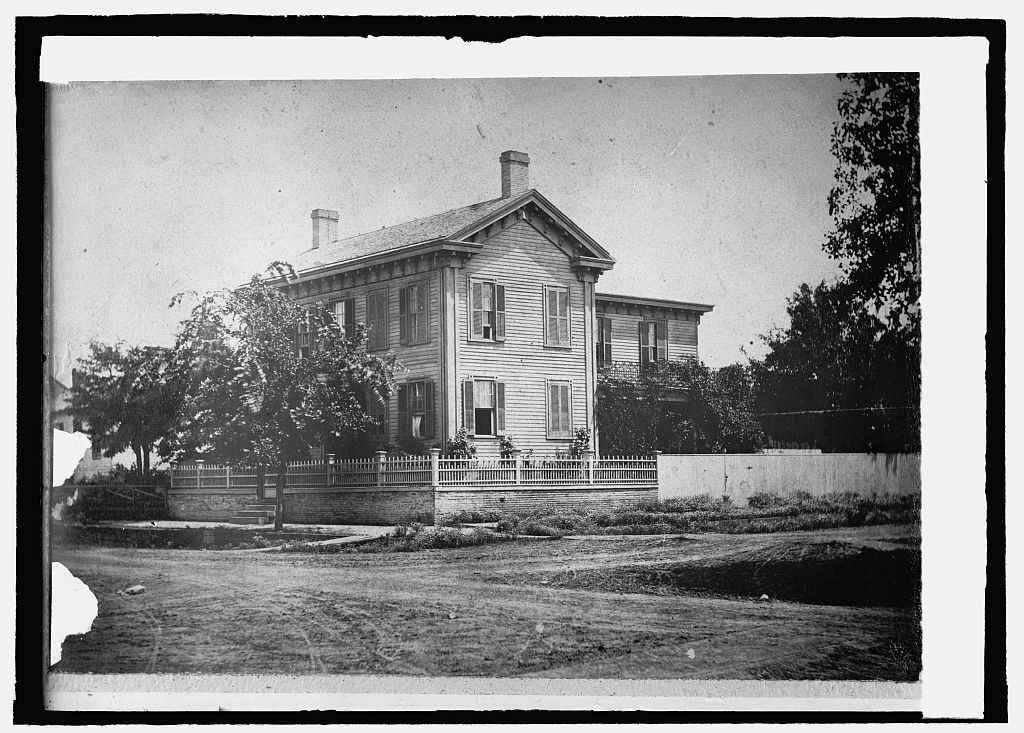

At no point was Lincoln’s presidential life ever free from the specter of death. From the moment he left his home in Springfield, Ill., on February 11, 1861, on his cross-country journey to the White House, Lincoln was plagued with constant threats against his life.

And many thought he would never even make it to Washington alive in the first place.

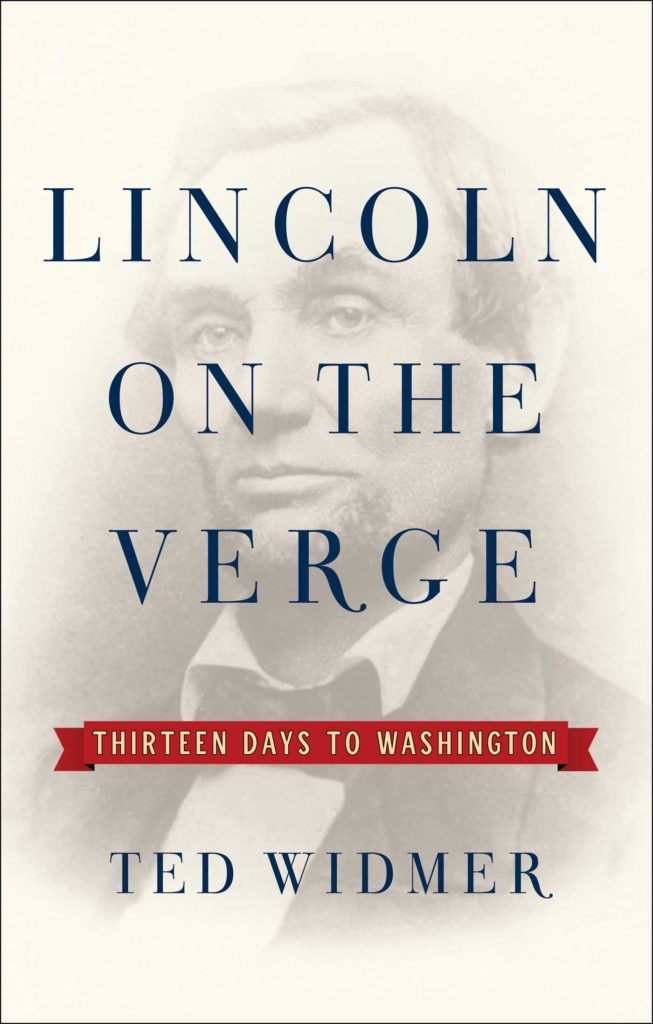

LINCOLN ON THE VERGE

Thirteen Days to Washington

Ted Widmer

Simon & Schuster

In one of the most fascinating history books of the year thus far, historian Ted Widmer takes the reader on Lincoln’s thirteen day journey to destiny — through Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Deleware and Maryland — on his way to lead a country at the precise moment it splintered apart.

This is also the story of the railroad and the telegraph as primary technologies of the day — but with their limits. The North’s comparatively sophisticated railway system allowed the president-elect quick passage to D.C. but not safe passage.

Every stop along the way presented a new set of hazards, great and small, intensified each day with news of secession and Southern conspiracies.

“To survive a train trip was a low bar for success, but so much was up in the air in February 1861 that Lincoln’s safe delivery would become, over the next thirteen days, a powerful symbol for the survival of democracy in America.”

And yet Lincoln on the Verge balances its unavoidable dire tone with that of a historical travelogue, with every stop on the journey described in brisk and vivid detail. Fortunately Lincoln had journalist Henry Villard with him, providing a rare insider’s view of this historical moment.

The whistle-stop nature of the story gives Lincoln’s journey an episodic feel, with a host of miniature dramas and foibles playing out in often amusing ways.

One anecdote plays in contrast to Lincoln’s stoic image. In Indianapolis, the president-elect delivers an off-the-cuff speech “comparing the South’s loose theory of union to ‘free love’ rather than a legitimate marriage,” a rather shocking reference for its time which repulsed those with “Victorian sensibilities.”

This is followed by a calamitous moment involving a missing speech in a cloakroom and the negligent behavior of Lincoln’s teenage son Robert. (This book is filled with such details of small, familiar setbacks. It’s been awhile since Lincoln has felt so human to me.)

Along the way, Widmer presents a very colorful and precise view of the cities and towns along the route — from Cincinnati’s slaughterhouse district to the “chaotic bog” known as the New Jersey Meadowlands.

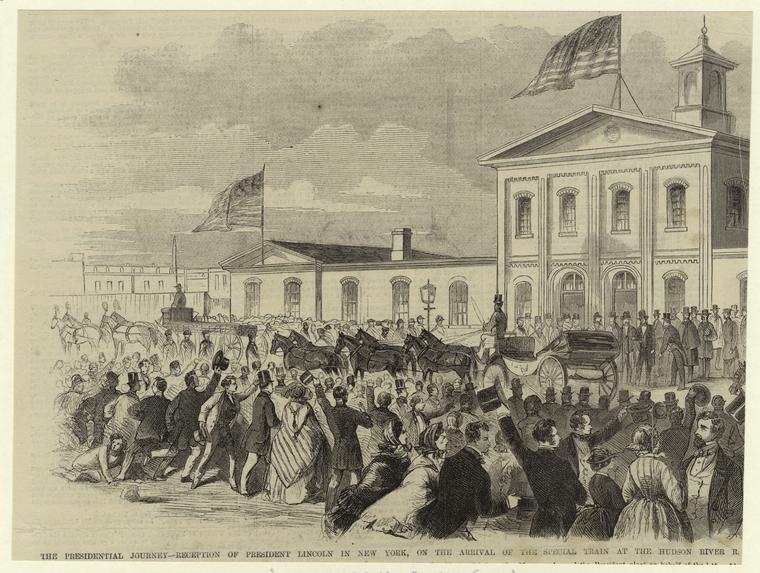

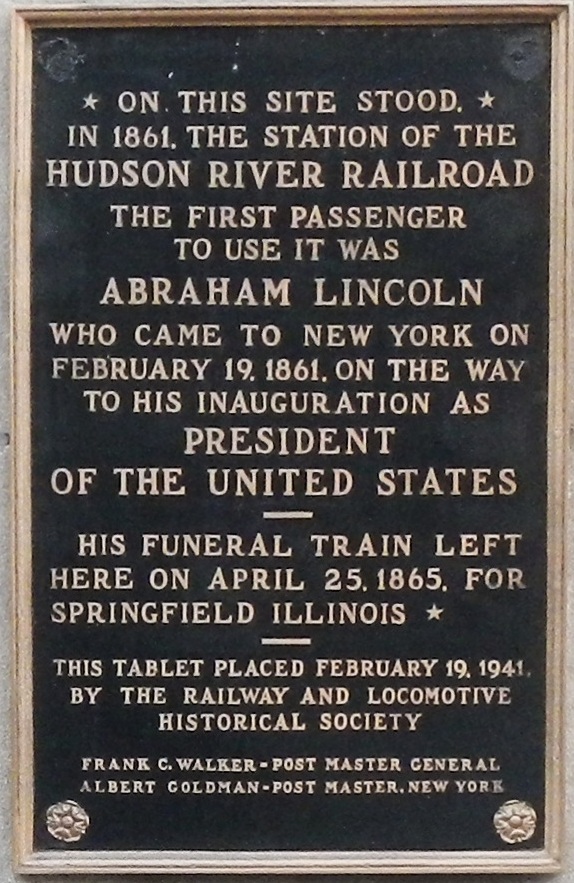

And of course — New York City. On February 19, 1961, Lincoln’s train pulled into Manhattan’s Thirtieth Street Depot (near today’s Hudson Yards) to throngs of supporters. “When it entered the depot, the crowd surged, nearly beyond the ability of the huge police force to restrain it.”

Over four years later, on April 25, 1965, another train would pull into this station on a return trip to Springfield, Illinois, carrying the body of Abraham Lincoln.