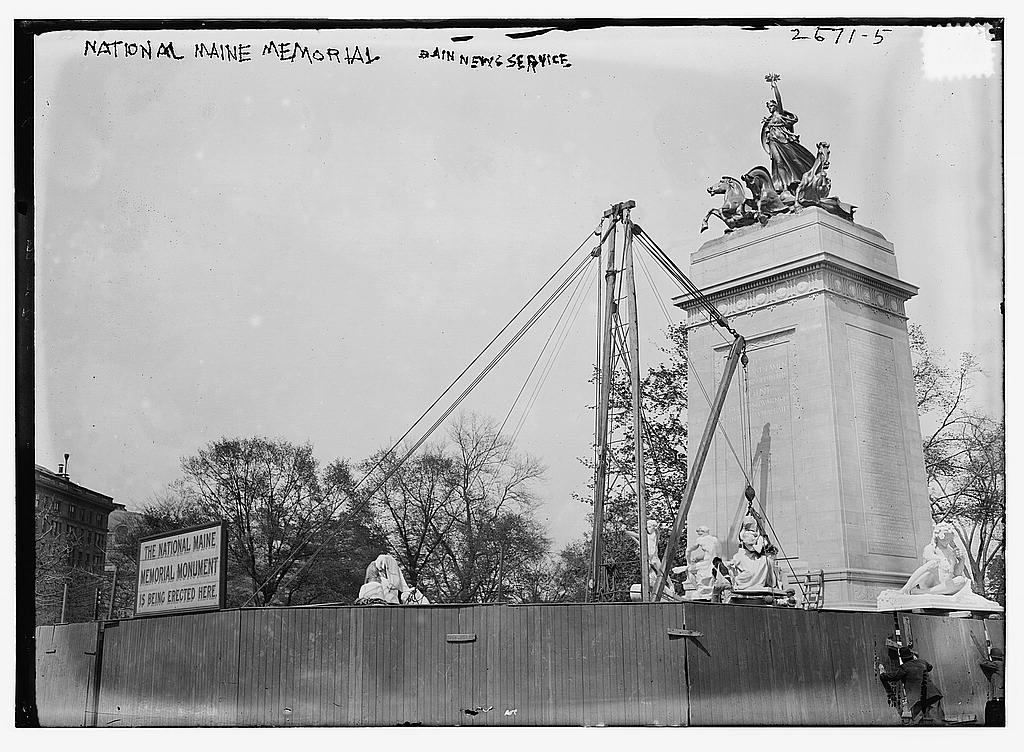

On Memorial Day in the year 1913, one of New York City’s great war memorials was finally unveiled — the Maine Monument, at the southwest corner entrance of Central Park.

The monument pays tribute to the 266 American soldiers who perished on the USS Maine, which exploded in Havana, Cuba, on February 15, 1898.

Given the various wars which have involved the United States since then, this event is sometimes overshadowed, but it so horrified and angered Americans that emotions helped fuel the conflict known as the Spanish-American War later that year.

This is often considered a war manufactured by New York publishers as anti-Spanish rhetoric in the papers — the seeds of so-called ‘yellow journalism’, featuring outlandish exaggeration or out-right fabrication to sell their product to New Yorkers — led directly into military engagement.

Newspapers were not only behind the causes of war; they were behind its monuments too. Within days of the explosion, William Randolph Hearst called for donations for a memorial to the Maine’s fallen crew.

Just as Joseph Pulitzer had done a decade earlier for the Statue of Liberty, Hearst went directly to its readers, young and old, to help fund a tribute to the Maine.

Given the wall-to-wall coverage of the war that year and the ample profits from newspaper sales, it’s strange that Hearst couldn’t just fund the whole thing himself.

Less than a month after the disaster, people around the country were fund-raising for the Maine Memorial.

In March 1898, a traveling comic opera crew was raising money in Oklahoma when its lead actress killed herself.

The following month, a vaudeville benefit at New York’s Koster & Bial in Herald Square was overtaken by sailors who took to singing patriotic songs from the balconies.

Hundreds of special benefits were hosted in theaters and stages across the country over the next decade.

It’s unclear how much of the proceeds ended up funding the monument, as it took well over a decade for money to be raised and its design — by New Jersey architect Harold Van Buren Magonigle, America’s go-to memorial designer of the Gilded Age — to be approved.

Magonigle enlisted his frequent collaborator Attilio Piccirilli to create the bronze and marble sculptures.

Some of that earnest enthusiasm seems to have disappeared when the memorial was finally dedicated on Memorial Day 1913.

According the New York Sun, leading New York artist erupted in “a storm of criticism” at the shiny, ostentatious design, with aesthetes calling the work a “misfit” and “a disgrace to the city.”

Many thought its relationship to the actual Maine was lost in vague theatrical symbolism.

“Architecturally and constructively the whole thing is cheap and bad.”[source]

The memorial was unveiled with a grand military parade and the attendance of ten warships in the harbor, including one from Havana.

There was, of course, one great conflict on everybody’s mind that day when, in the official ceremony, sworn enemies Hearst and Mayor William Jay Gaynor met at the unveiling. (Among many grievances, Hearst had unsuccessfully run against Gaynor for mayor in 1909.)

With utmost restraint, Gaynor managed to shake Hearst’s hand without punching him in the face.

Two years later, a second memorial to the Maine was placed in Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, D.C. And in 1926, a lavish monument was placed in Havana, Cuba.

2 replies on “Remember the Maine Monument!”

No mention of the great model Audrey Munson?

no mention of any of the models that sat for this???