Owney Madden was one of New York’s most infamous gangsters, a bootlegger and murderer who seemed to cross paths with every major cultural marker of the Roaring 20s. He opened the Cotton Club (with Jack Johnson), dated Mae West, and operated a liquor smuggling racket that catered to the city’s busiest speakeasies.

In essence Madden was the blistering face of Prohibition-era Manhattan.

And in 1935, he left it for good to go live in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

THE VAPORS

A Southern Family, the New York Mob and the Rise and Fall of Hot Springs, America’s Forgotten Capital of Vice

By David Hill

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

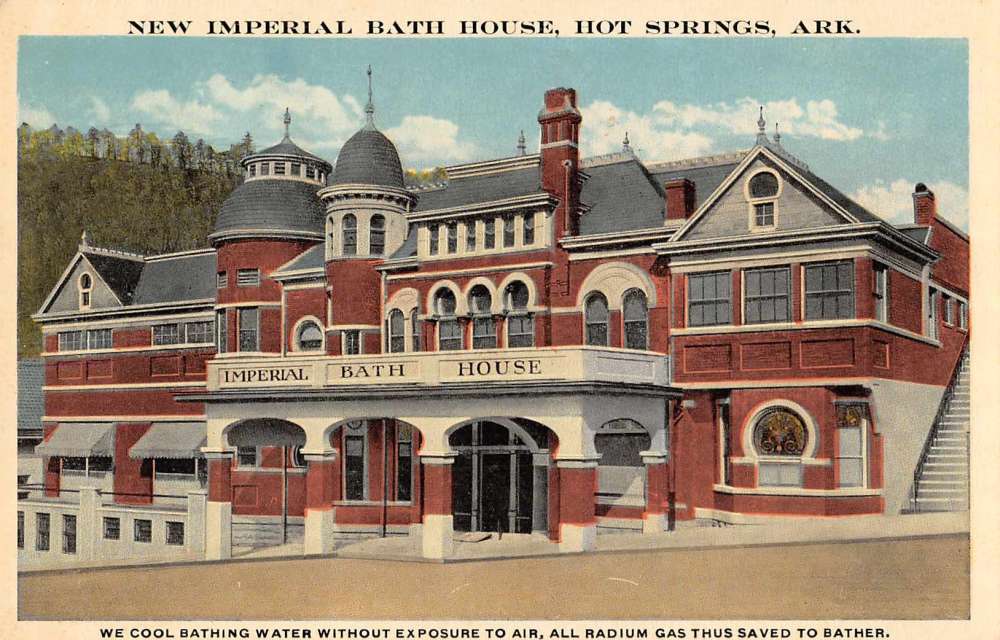

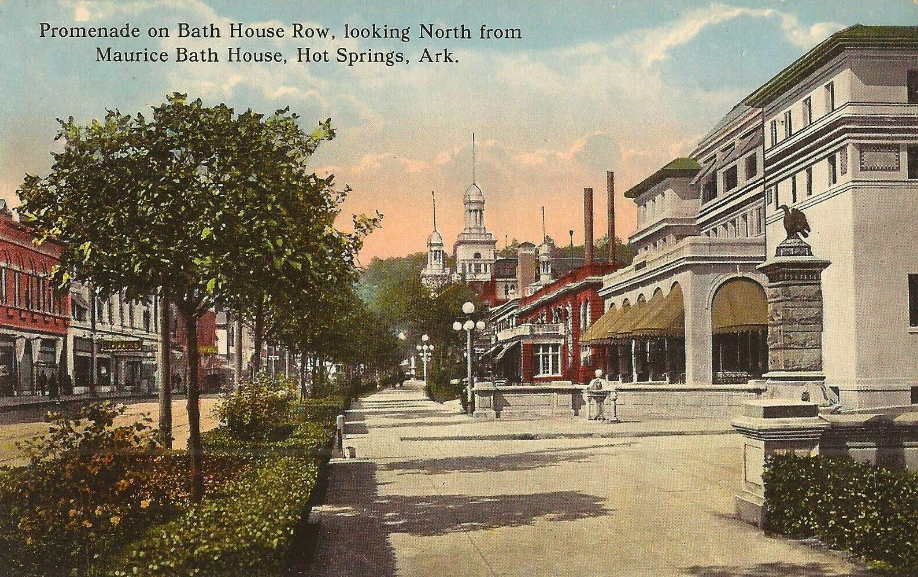

For a time, it seemed that Hot Springs, not Las Vegas, would be the vice capital of the United States. In David Hill’s captivating and beautifully written The Vapors, we’re re-introduced to an overlooked corner of history, a historic spa town with troubling secrets and a sleazy underbelly.

The Vapors was one of the last in a series of glamorous casinos and resorts which graced this mountain town during the 20th century, well established as a destination for illegal gambling by the time Madden arrived.

With Prohibition repealed, organized crime lords looked to gambling as their next best bet.

In the 1930s, Vegas was an uncertain proposition, sprouting haphazardly in the middle of the desert.

But here in Hot Springs, tourists had luxuriated in healing spring waters for decades. Sports heroes, politicians and musical entertainers all came here to relax. Lawmakers and law enforcement often looked the other way as it frequently benefited them to do so.

Madden was a celebrity in Hot Springs, a liaison between civic leaders and visiting gangsters, a man with unique powers who nonetheless had to learn the more delicate game of political control.

“Owney’s days of killing his enemies were long behind him,” writes Hill, “but it sure must have seemed cheaper than winning a fair election in Hot Springs. ‘You know, in my day, back in New York, how I’d have handled this…..’ Owney said to the gamblers. ‘No, no, no!’ they quickly cut him off.”

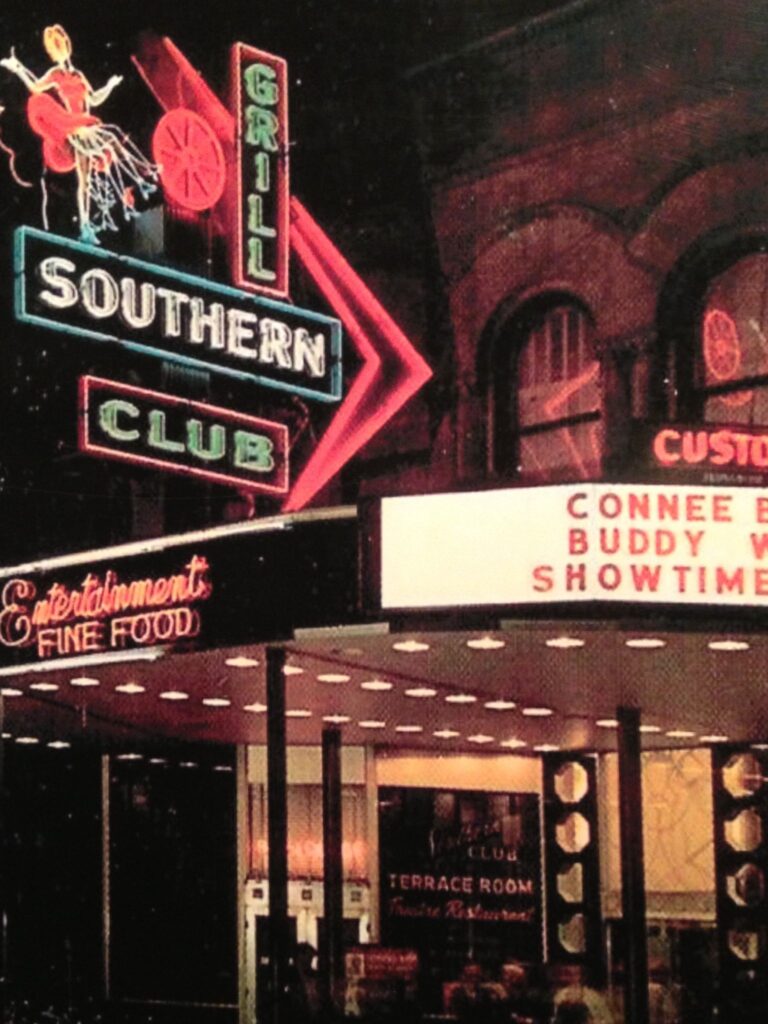

Madden’s roost was the Southern Club, an Arkansas variant of club’s like his old Cotton Club. Hill writes:

“At the Southern, Owney was treated with discretion, not as if he were anyone else off the street, but not as anything special, either. The patrons knew to keep their distance. In Hot Springs, people had grown used to seeing famous folks out and about, and had learned to act like it wasn’t any big deal. In this way the spa had a lot in common with much larger cities, and the famous appreciated it as a form of hospitality. The notorious, even more so.”

The fate of Hot Spring’s lucrative gambling scene — and all its vice-ridden sideshows — rested on shady deals with law enforcement and local officials.

The city often resisted the presence of notorious gangsters for fear of the attention; in fact, another New York mob boss Charles ‘Lucky’ Luciano, who had considered Hot Springs a sort of gangster’s retreat, was arrested here in 1936.

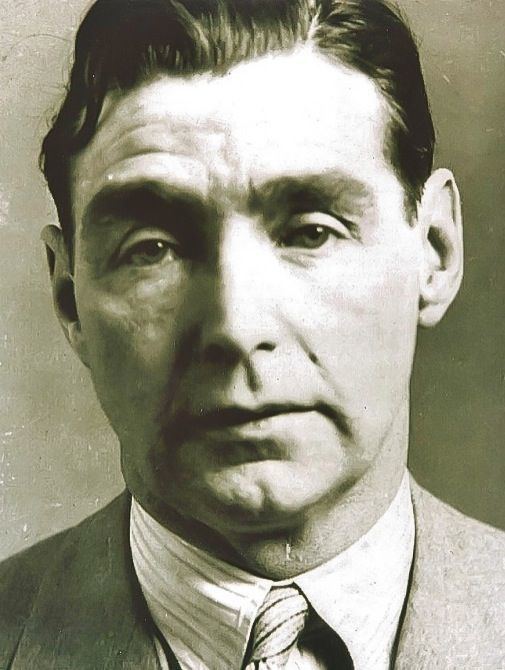

Below: Owney Madden in his later years

Hill reconstructs the resort town with such vivid attention to detail — a haven of mist, fedoras and cheap-lipstick glamour — through exhaustive research and interviews. (Hill, who lives in New York, is a native Arkansan and you feel it.)

Alongside Madden, in a simple stroke of balanced narrative that really elevates The Vapors into the realm of prize-deserving literary magic, the author also follows the stories of Madden’s protege Dane Harris (the “boss gambler” of Hot Springs) and a tough lady named Hazel Hill, raising two sons during the city’s most tumultuous years.

Hazel’s story is told with an added degree of richness and sympathy, as well it should. She’s the author’s grandmother.