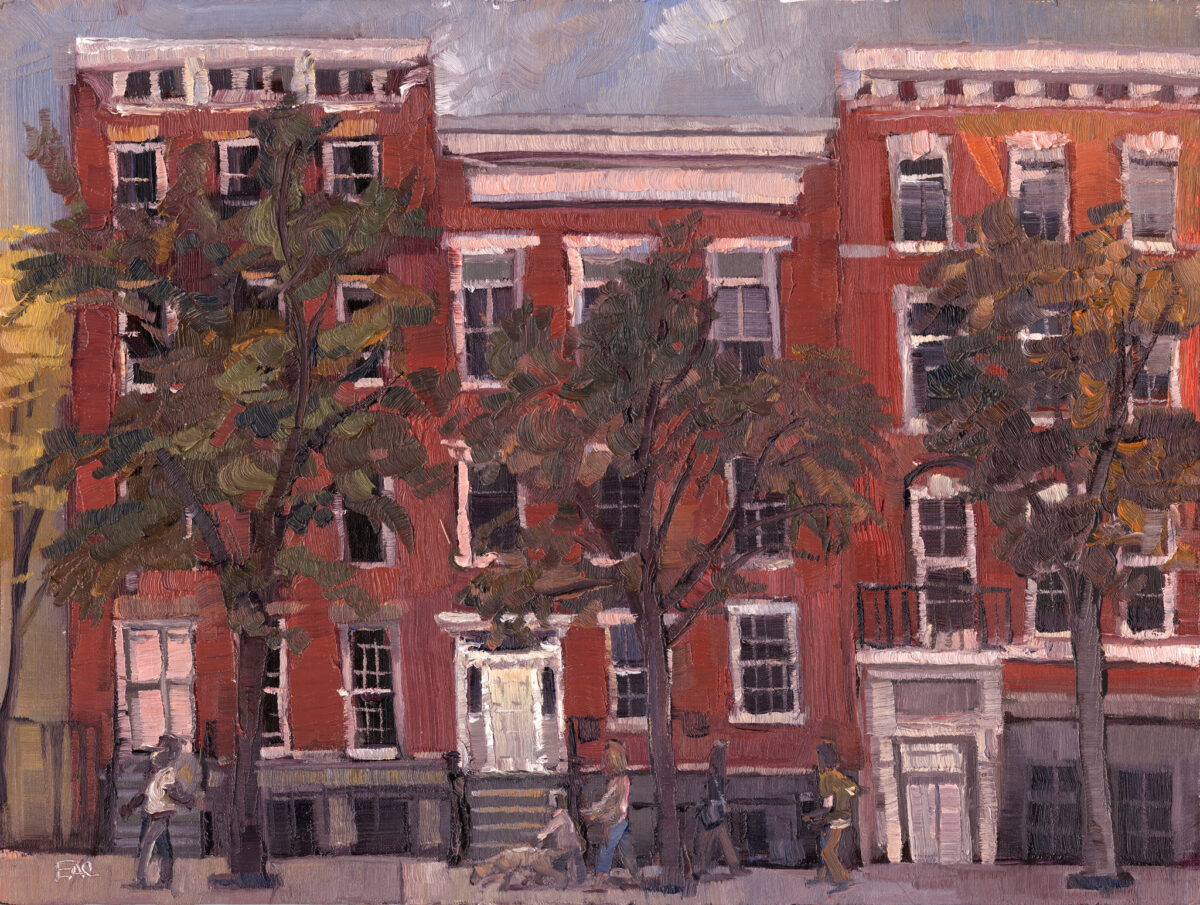

If you’re looking to read something about the possibility of doing absolute good in the world, then a story about the Henry Street Settlement is a good place to start.

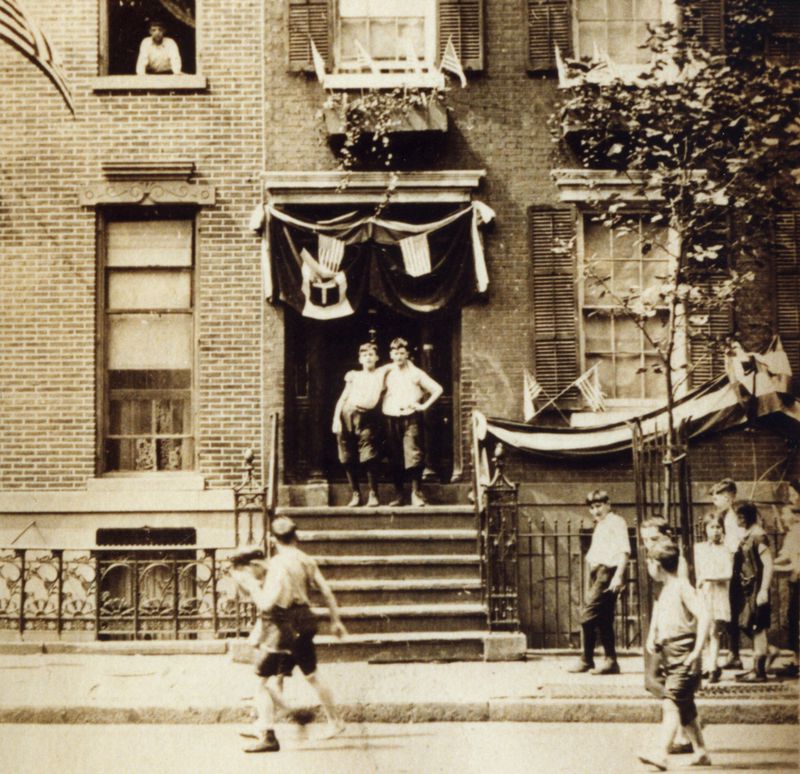

The Lower East Side settlement house, founded by Lillian Wald in 1893, became not only a salvation to the hundreds of thousands of immigrants in the densely populated neighborhood, it created a template for social work and community care during the Progressive Era.

THE HOUSE ON HENRY STREET

The Enduring Life of a Lower East Side Settlement

by Ellen M. Snyder-Grenier

Washington Mews Books

But in a new book about Wald and her historic institution, curator Ellen M. Snyder-Grenier makes the convincing case that many roads of 21st century social justice pass through the doorway at 265 Henry Street as well.

Wald charted this ambitious project as a means to provide individualized nursing care to those in the Lower East Side who could not afford or were too unwilling to visit hospitals. Writes Snyder-Grenier:

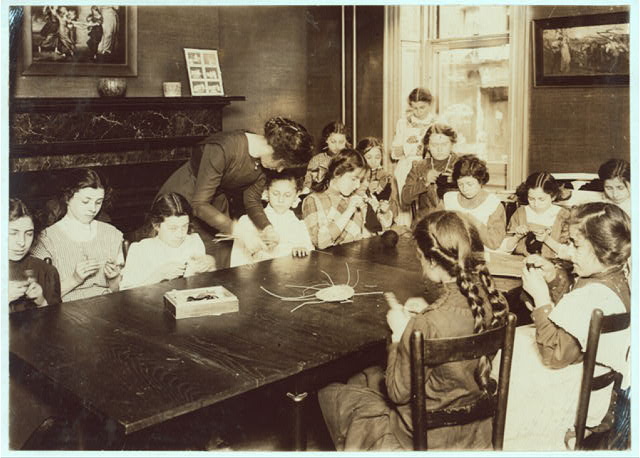

“Warm, inviting, and welcoming, the house on Henry Street was more than just a house; it was a home. Settlement women like Wald drew on a Victorian model of middle-class women presiding over their homes as wives and mothers with care, moral uplift and nurturing, redefining it for their modern endeavor, rejecting maternalism’s limiting aspects and owning its best and most useful parts.”

But Wald (pictured above) knew early on that struggling communities needed more than physical care. They needed advocates. “[H]er goal was not only to nurse the sick but to address the underlying social problems to poor public health.”

The Henry Street Settlement became a testing ground for social reform. Every child in America has been positively affected by Wald’s crusades, local endeavors which took wing across the country — for playgrounds, for free school lunches, for special education, for child labor laws.

But Wald (and the Settlement, the fullest extension of her personality) also fought for gender equality and organized against racial injustice.

She expanded the Settlement into black neighborhoods like San Juan Hill and was on the board of the directors for the NAACP. And during wartime, she and the Settlement championed for peace.

Naturally, during conservative periods, Wald and her “seditious activities” were painted by some as anti-American.

After Wald’s death, Helen Hall became director of the Settlement, and for over thirty years she led the institution in directions that would have made Wald quite proud.

In particular, Hall and the Settlement became instrumental during the development of certain New Deal programs. Although, from the vantage of a social worker, FDR’s visionary programs did not go far enough.

“Hall was unhappy about what the legislation had left out — compulsory (universal) health insurance — an omission that continues to resonate in American life in politics.”

In fact the parallel with modern progressive politics is made so clear in The House of Henry Street that the book even comes with a forward written by Bill Clinton, who visited the Settlement in 1992:

“As I looked around, I saw the best of America — young and old, immigrant and native born — all there because they wanted to create a better future for themselves and their families.”

You can also check out our show from last year Saving The City: Women of the Progressive Era for more information on Wald and a tour of the Henry Street Settlement.