There once was a modest basement nightclub in an old West Village building which opened the door to a revolutionary (and now obvious) idea in New York City music and delivered one of the most significant moments in all of music history.

In the 30s Midtown Manhattan clubs were alight with the bourgeoisie, tuxes and evening gowns, tables and banquettes of rich white people drinking champagne, and often entertained by Black performers borrowed from the Harlem music scene.

It was putting on the ritz, it was dancing cheek to cheek.

It was embodied within the phrase ‘café society‘, coined by the one of the scene’s wittier celebrities Claire Booth Luce, playwright of The Women and a darling toast of Broadway.

But there was also something saccharine and square — and segregated — about those Midtown haunts. Things were wound too tightly.

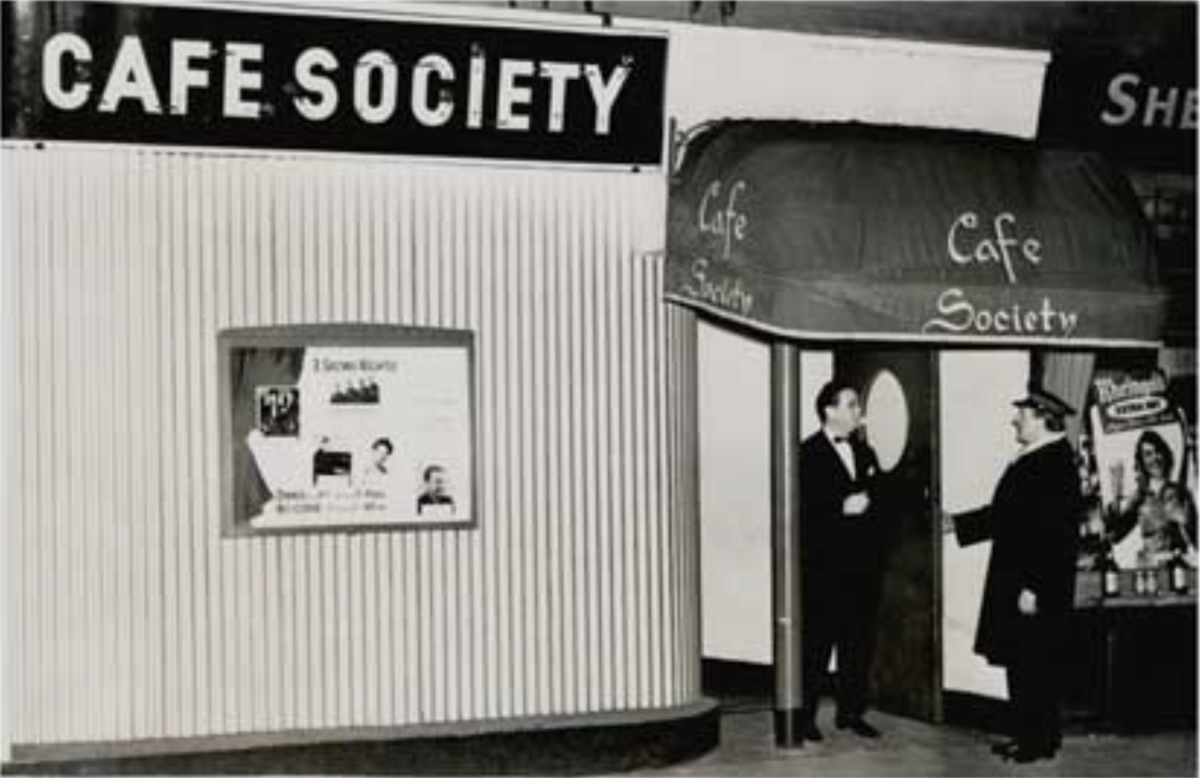

What would become one of the New York music world’s most fertile spots for musical innovation was far, far downtown from the ‘real’ nightlife — at 1 Sheridan Square in the West Village.

Café Counter Culture

New Jersey shoe salesman Barney Josephson had an affinity for jazz music — partially grown from visiting the bawdy clubs of underground Berlin — but grew irritated at the race segregation, which even occurred in Harlem, at places like The Cotton Club.

Josephson envisioned a venue where musicians of any color could perform — and audiences of any color could enjoy it — but such a notion seemed to fly in the face of modern ‘café society’ culture.

“I wanted a club where blacks and whites worked together behind the footlights and sat together out front. There wasn’t, so far as I know, a place like that in New York or in the whole country.”

So, acquiring his Greenwich Village location, what a better name to call this rather kooky experiment than Café Society?

Luce, knowing good irony when she saw it, even encouraged the bar’s lusty slogan: The wrong place for the right people.

Open (To All) For Business

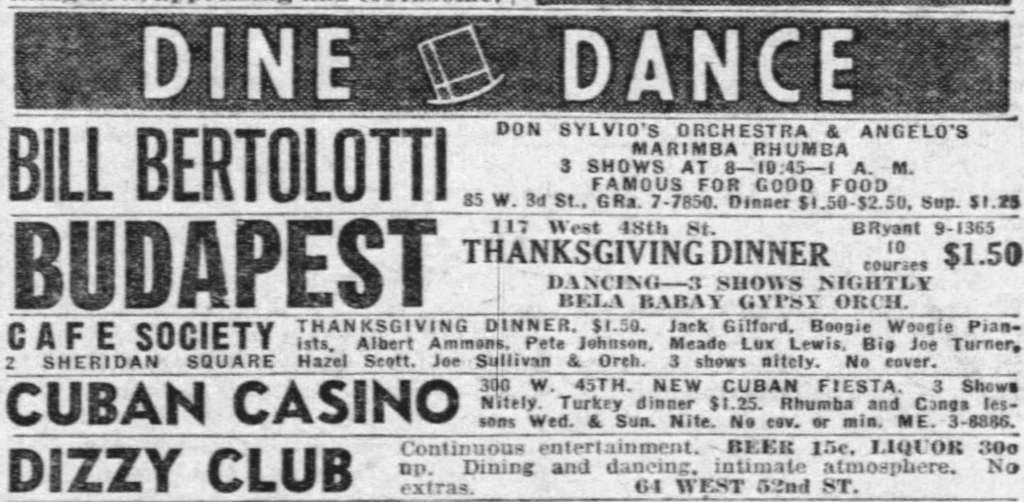

Opening on December 18, 1938, Café Society was festooned in wacky caricatures of music stars, comedians and personalities of the age. Walls were muralled by creations from local artists.

The club doorman played with the notion of informal glamour, wearing a tattered top hat and white gloves with the fingertips ripped off.

But there was none of the silly, castoff frill of the uptown fare — “no girlie line, no smutty gags, no Uncle Tom comedy“.

What happened on its stage was far from typical.

Below: The Boogie Woogie pianists, Cafe Society, 1941. Take note of the murals on the walls.

Josephson began hosting performers of all stripes, many taking to a mixed stage for the first time in their careers.

Over the course of its ten-year run — and that of a second location, coyly placed at 58th and Park — Josephson and his partners would host dozens of soon-to-be jazz stars, in many cases paving the way to their success.

Art Tatum, Lena Horne, Sarah Vaughn, Mary Lou Williams, Lester Young, Burl Ives, the Golden Gate Quartet, Ella Fitzgerald — in fact its easier to make a list of jazz and pop music icons who didn’t perform there.

But Café Society’s biggest claim was there from the beginning.

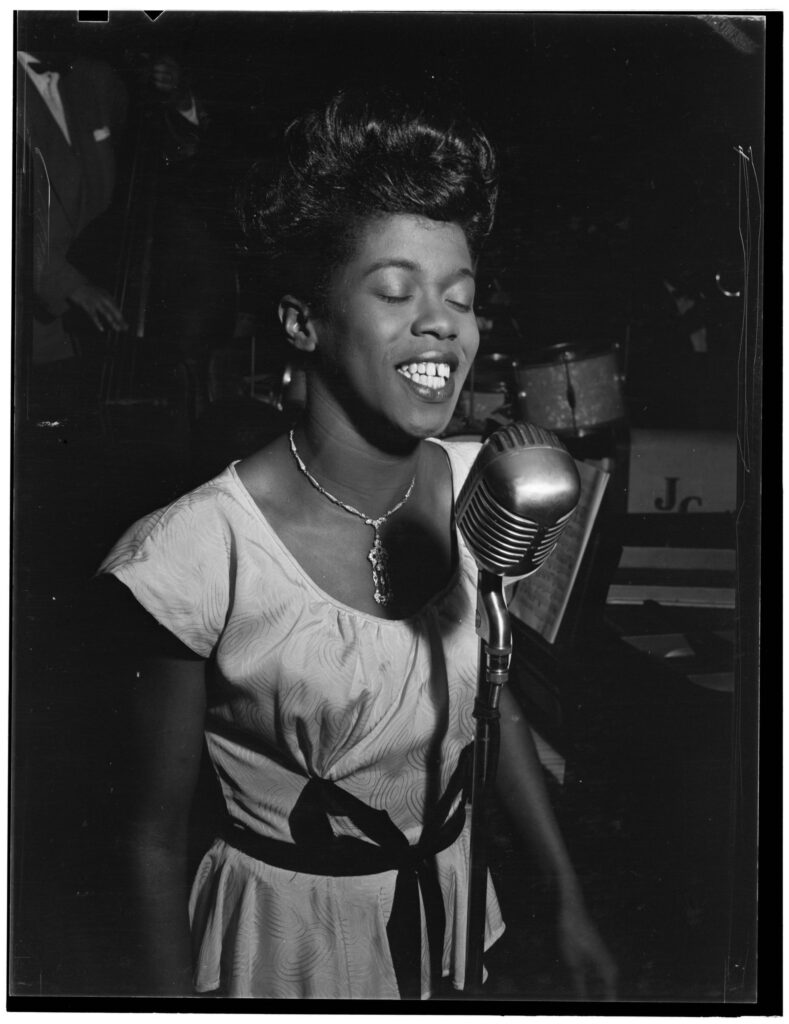

On opening night, a young woman took to the microphone. She achieved some success on the New York stage by this point and had even snagged a recording contact with Columbia Records.

But the legend of Billie Holiday would begin here — on opening night.

A Song For Lady Day

To have Holiday as your in-house singer (for nine months!) would have been an honor enough.

To give her — and the world — a defining musical moment, well, that’s New York.

Café Society naturally took on a liberal, left-leaning clientele and with that, a political edge.

Josephson presented a song to Holiday that he had heard at political gatherings, a piercing tune about lynching, one that forcefully reminding listeners that violence and discrimination still very much existed outside the doors of his club.

Billie was originally indifferent to the song, written first as a poem “Bitter Fruit,” by a white Jewish schoolteacher Abel Meeropol; then after contemplating it, considered it too bold.

But she was eventually convinced to sing it, and on three consecutive nights early in 1939, Holliday ended her sets with the song — “Strange Fruit.”

A spotlight tightly focused on her face, she stunned the audience with its searing intensity.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swingin’ in the Southern breeze

Strange fruit hangin’ from the poplar trees….

And then she left the stage, not returning to hear the thundering applause.

It was theater at its finest; thousands of less talented chanteuses would search to recapture the drama in dozens of Village clubs and cabarets, from then to today.

The Café Society ‘revolution’ would not last long.

Josephson’s brother Leon was being investigated for communist ties, and Barney soon felt the heat of J. Edgar Hoover and his House Un-American Activities Committee.

The FBI even staked out the clubs, photographing patrons, and Hoover soon ‘opened a file’ on Barney himself. Both locations of Café Society were closed by 1950.

But Josephson managed to pick himself up and soon opened another influential downtown jazz club, the Cookery, which stayed opened into the 1980s.

Holiday entered the pantheon of musical legend, at immense cost to herself through her abuse of drugs and alcohol. (For more on her New York story, check out our catalog show called Billie Holiday’s New York.)

But for a moment, that gritty nightclub became the center of the musical universe.

Most music critics agree that Holiday’s original performances of ‘Strange Fruit’ at Café Society are among the most influential musical moments of 20th century and basically constitute the birth of political activism in popular music.

You can visit the location of the former Café Society simply by taking the subway to Sheridan Square (actually a triangle) and going to its eastern side.

2 replies on “The story of Café Society where Billie Holiday found her song”

Hi guys! I LOVE your show. I moved to Florida from NY to see about my parents. But I spent my childhood in Bklyn and my married life in Queens. So, spending a little time with you just puts me in a comfortable, cushy place. :-D.

I just heard the Billie Holiday segment and wanted to let you know that Time Magazine named “Strange Fruit” Song of the Century.

I’m going to look for a space I can comment on miscellaneous/new stuff. Thanks again, fellas!

[…] was generated by Bing’s Image creator AI, tribute to Cafe Society of NYC is my own […]