With a new mayoral race on the horizon in New York City we think it is time that you Know Your Mayors! Become familiar with other men who’ve held the job, from the ultra-powerful to the political puppets, the most effective to the most useless leaders in New York City history.

This longtime feature of this website is being rebooted with new articles and newly researched and refreshed earlier entries in this series. Check back each week for a new installment.

Edward Livingston

Term: 1801-1803

The Mayor Who Went On To Do Better Things

On the spectrum of interesting folks who have occupied the mayor’s seat, Edward Livingston must certainly be noted as the defining example of turning your life around.

In 1801 Livingston became the mayor of New York City. Two years later, he left the job in total disgrace, run out of the city due to a financial scandal. He would never work in this town again.

And then things got really interesting.

Life With The Livingstons

Livingston, born in 1764, was a member of the rich and powerful Livingston clan. There were Livingstons in all aspects of American life — political, social, financial. It was as close as you got to a brand name in the Colonial era.

Edward benefited from this common ancestry. He was just eleven years old when his father Peter Van Brugh Livingston became president of New York’s First Provincial Congress in 1775. Another relation Philip Livingston signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776. And Edward’s older brother Robert Livingston (pictured below) would become New York chancellor.

Young Edward barreled into his career, an ambitious lawyer who settled in New York following the Revolutionary War. Everybody knew his name; he was unsurprisingly a great success. What could go wrong?

Rising Star

In 1795, Beau Ned (as he was called) was elected to represent New York in the U.S. House of Representatives, aligned with the ascendent Democratic-Republican Party, putting him in good graces with Thomas Jefferson, New York Governor George Clinton and various politicians in opposition to the Federalists.

The mayor of New York at that time — Ricard Varick — was a Federalist.

When Jefferson won the presidency in a hotly contested election in 1800, Edward Livingston found himself on the right side of many lucrative political appointments.

In 1801, the governor chose him for U.S district attorney and then, a few months later, Livingston was also appointed mayor. (See entries on Varick and James Duane to understand why these men were even allowed to hold multiple jobs.)

A Hot Time In The Old Town

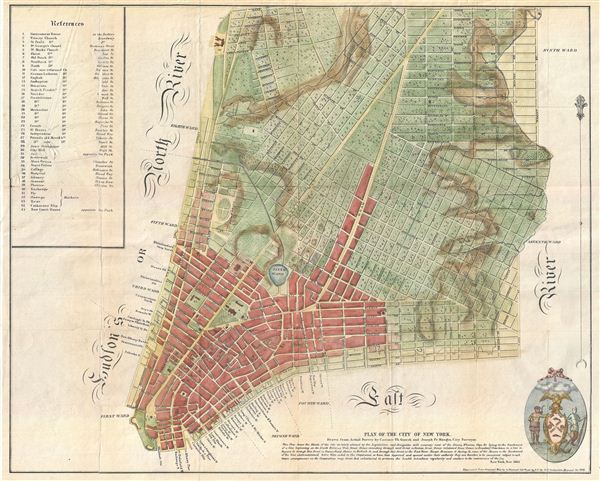

Suddenly, Livingston had become mayor of the biggest city in the new nation — a whopping 60,482 according to that year’s census. His opposition to the policies of former president John Adams served him well for a time under the new auspices of a Jefferson presidency.

But the year 1801 in New York was undeniably a volatile one and post-war optimism had given way to bitter skepticism and political chicanery.

New York senator Aaron Burr, Jefferson’s running mate, was nearly voted president in an electoral-college snafu.

Jefferson’s nemesis Alexander Hamilton — who would later be shot and killed by said running mate — would baste his thoughts in the newly created New York Evening Post.

Nearby, a young aide named Washington Irving worked in a law office.

A City Sickness

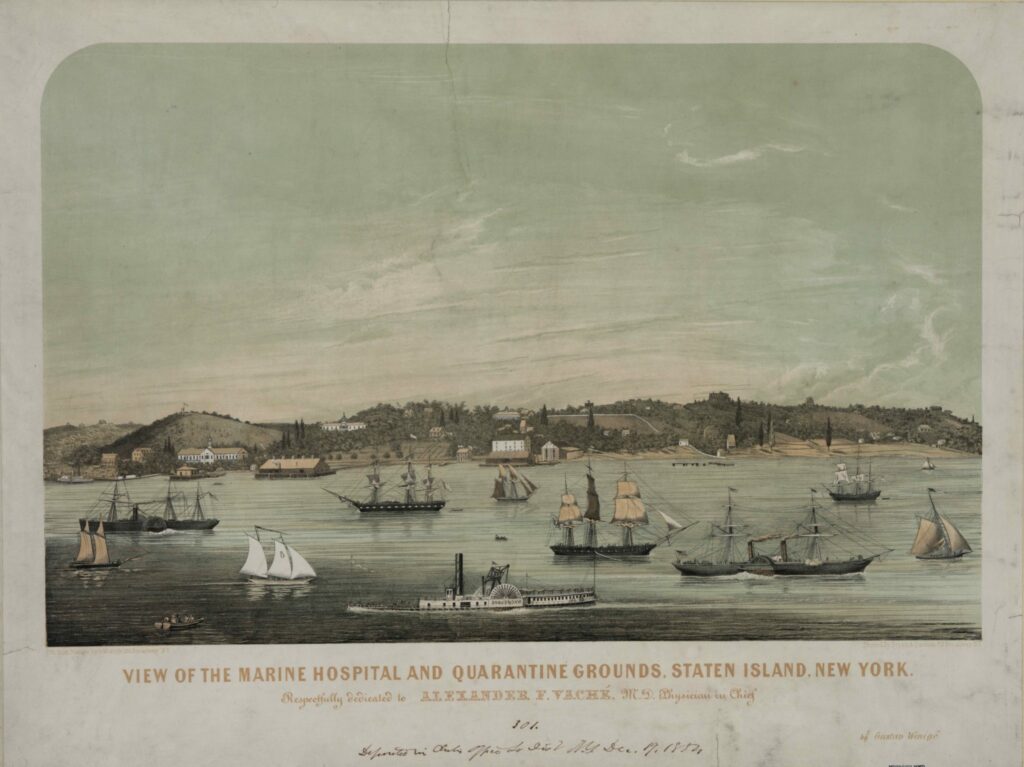

Unfortunately for Livingston the early 1800s were simply not a great time to be living in New York City. In fact, during his tenure, Edward Livingston almost died of yellow fever.

New York was hit ferociously by a yellow fever epidemic in 1798 and the affliction returned almost annually, never fully dissipating.

In 1803, a second epidemic hits New York and hits hard. Hundreds would die, thousands would flee. The stoic Livingston would manage to keep the city operating, even as he himself would become sick and nearly die.

In Disgrace

He recovered only to meet with a scandal that would nearly ruin him.

In the summer of 1803, it was discovered that $45,000 had gone missing from the city’s custom-house fund. While it was determined that a clerk from the district attorney’s office had actually stolen the money, it was Edward Livingston who took the hit politically.

“Although his own integrity was not in question,” according to the book Gotham, the ensuing scandal not only forced Livingston to give up both the state attorney job and the mayor’s seat, but he actually had to sell his property to repay the government.

Livingston had disgraced the family name.

The Ultimate Second Act

Nearly penniless and humiliated, Edward decided to leave New York for good in 1803.

Penniless but not, of course, without family connections.

In 1804 moved to New Orleans, recently purchased from the French by the federal government as part of the Louisiana Purchase. The team negotiating that deal included James Monroe — and Edward’s older brother Robert Livingston.

During the War of 1812, Edward was active in the defense of New Orleans and even served as the aide-de-camp to General Andrew Jackson. The two became close friends.

By 1826, Livingston was successful enough again with his own law practice in New Orleans that he was able to pay back the government all the money he owed plus interest — or almost $100,000, no petty sum back then.

That same year, Livingston would shape American civil policy with a series of influential penal and judiciary codes for the treatment of prisoners, now referred to as the Livingston Code. While rejected by the State of Louisiana, the legal reforms would live on to shape ideals about incarceration and the death penalty.

Because of these reform codes, Edward Livingston is considered one of the great American legal geniuses of the early 19th century.

After notable stints as representative and a Senator for the State of Louisiana, he became a persuasive Secretary of State for President Jackson from 1831-1833. Edward Livingston died on May 23, 1836.