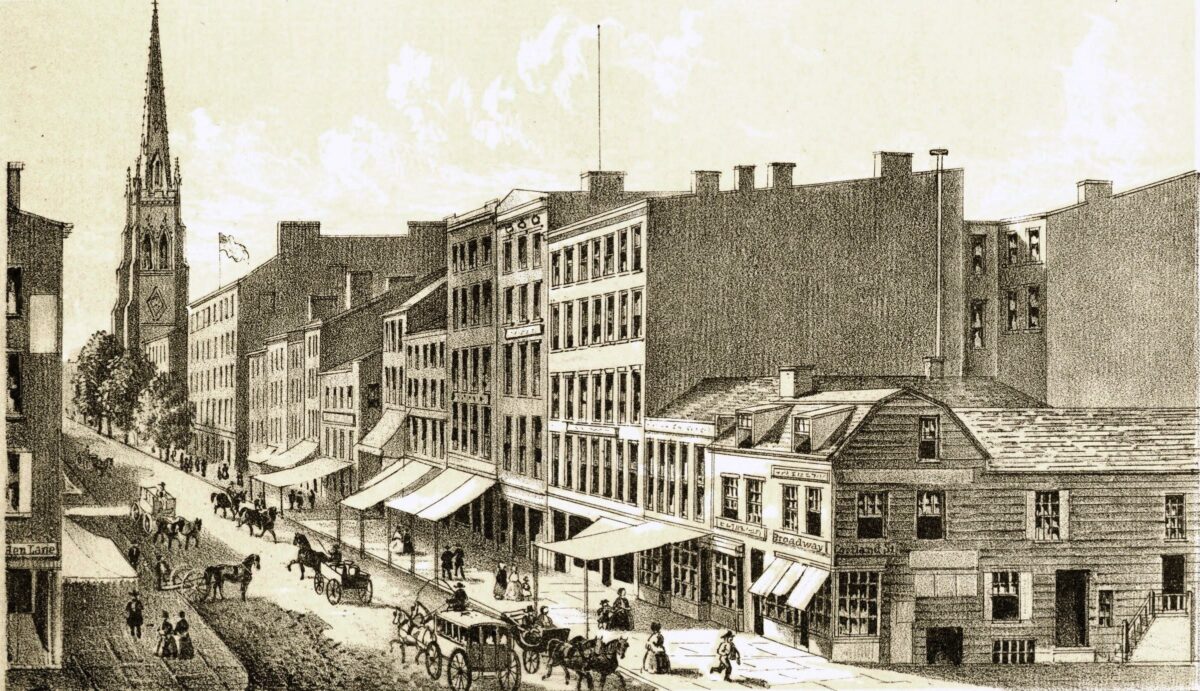

We’re getting a new mayor! So we think it is time that you Know Your Mayors. Become familiar with other men who’ve held the job, from the ultra-powerful to the political puppets, the most effective to the most useless leaders in New York City history.

This longtime feature of this website is being rebooted with new articles and newly researched and refreshed earlier entries in this series. Check back every other week for a new installment. Read past articles here.

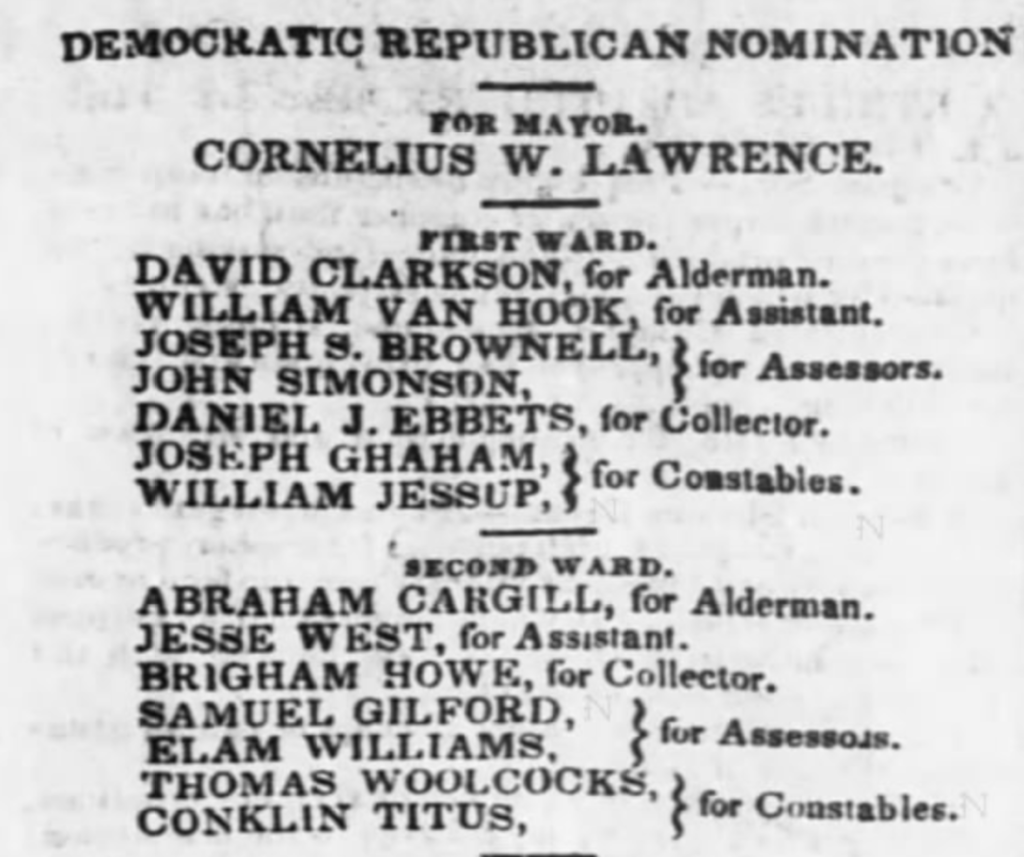

Cornelius Van Wyck Lawrence

Term: 1834-1837 (three terms)

When did New Yorkers first start electing mayors — directly? When did voters first go to the polls and select the new mayor themselves? The year was 1834 — and, oh boy, did it not go smoothly.

In the first few decades following the Revolutionary War, mayors were chosen by the governor and a state-side appointment committee. Then, from 1821 to 1834, the position was appointed by vote of the Common Council, an elected body equivalent today’s City Council.

The Council often chose prominent businessmen with high profiles — such as the sail-maker Stephen Allen or the well-connected attorney William Paulding.

But the city charter was amended in 1833 to allow the position of mayor — a lucrative post with rising visibility in a growing city — be directly chosen by New Yorkers.

Or rather, directly chosen by those who comprised the voting body — white male New Yorkers. (Black men could vote if they owned property; but as slavery in New York was only abolished in 1827, few men actually did, save for those in places like Seneca Village.)

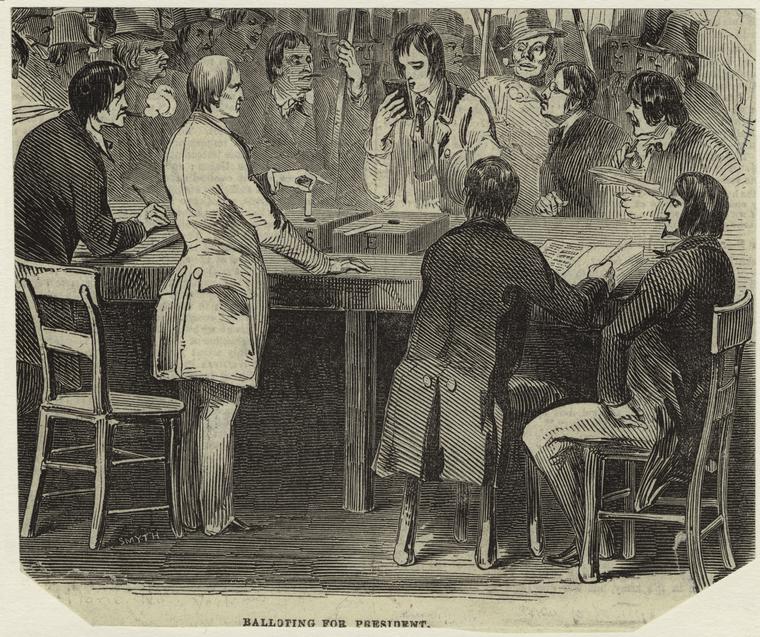

Today’s modern election process is relatively incorruptible, even tranquil, compared to the riots and ballot stuffing and outright vote forging of yore. Nobody openly destroys ballots in the street anymore, and that’s a good thing.

But democracy in its purest form relies on a certain degree of faith. The direct election process — the collection and counting of ballots, the integrity of an honest count — has the potential to be quite chaotic.

And no election in New York City has been as chaotic — or as bloody — as that very first mayoral election in 1834.

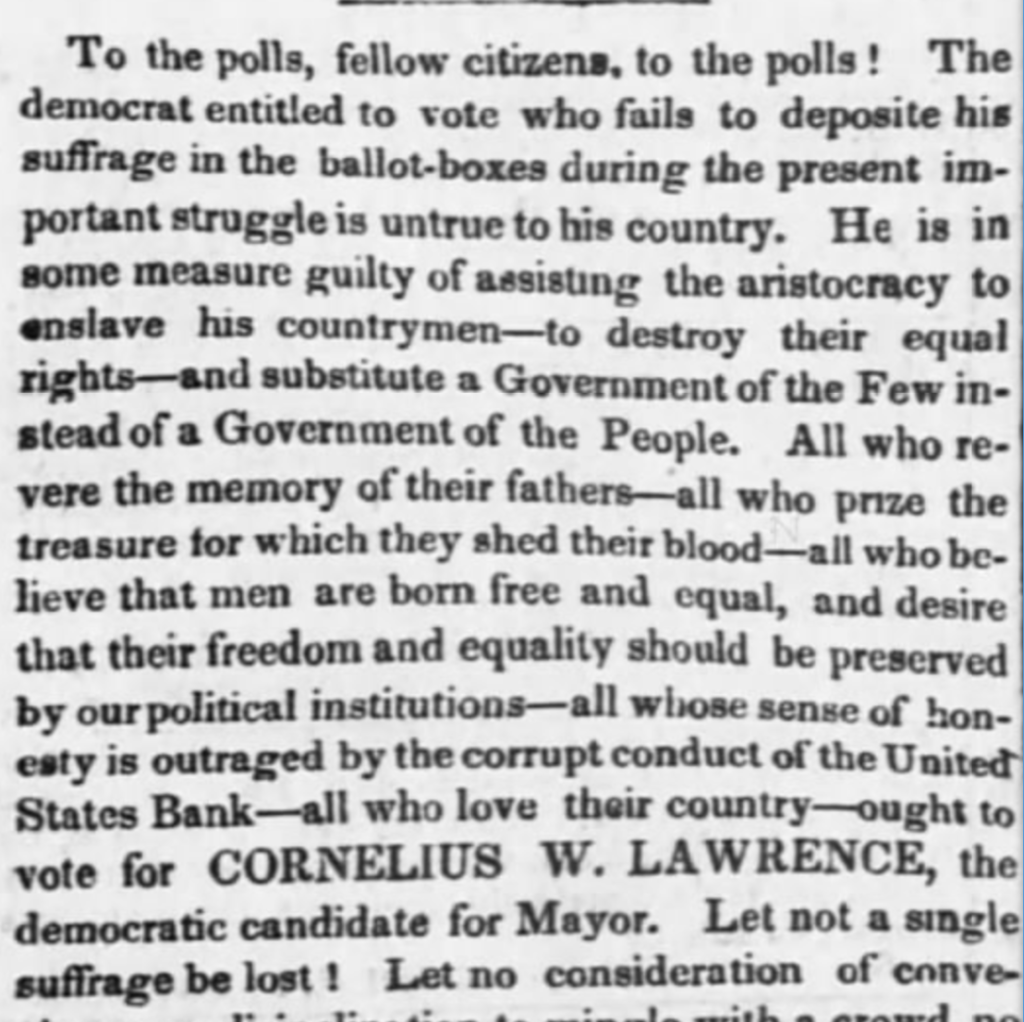

In 1834, New Yorkers were thrilled with the real possibility of a city leader not beholden to the whims of its Council, a membership whose intentions were often deployed straight from the meetings of political machines and did not reflect the will of the people.

But local politics can become overshadowed by national concerns. As a result, direct election for the office may fail to correct this sort of favoritism. In fact, if the conditions are right, the will of the people can be bent to adhere to the most elitist of principles, using the sometimes benign instrument of populism.

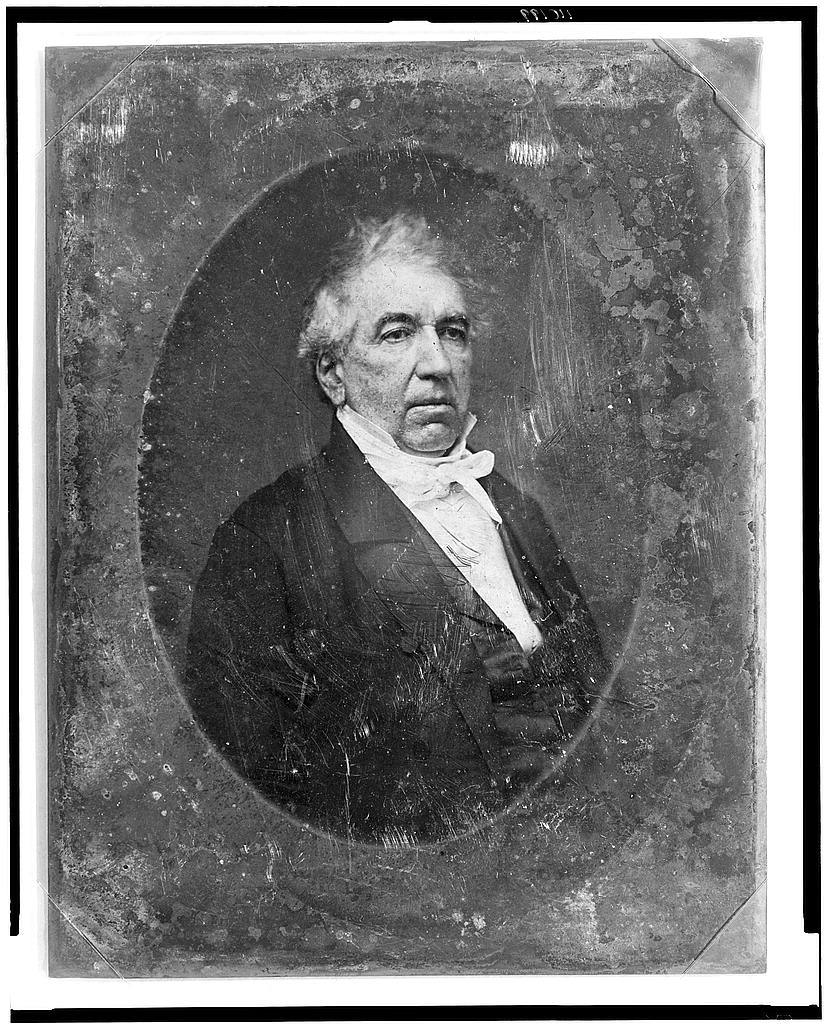

Such was the case of the man who would become New York’s first democratically elected mayor in 1834 — Cornelius Van Wyck Lawrence.

Lawrence, a wealthy New York merchant, was born in 1791 in Flushing, Queens County, a member of the old Dutch Van Wycks. (His ancestor Cornelius Van Wyck built the historic Van Wyck Homestead in Fishkill, New York.)

In 1833, he became a Democratic state congressman known for believing one thing, and voting another, especially if it benefited himself financially. He was known to cry at the podium as he voted with his party.

From a biography on Martin Van Buren: “[Lawrence], the crying congressman, the weeping stock-jobber could have resigned had he disliked the party drill — but it brought him plunder, and he blubbered and held on, and afterwards he lent his name as a candidate for the mayoralty to uphold the gamblers he voted with in public…”

Yet the election was much larger than one man — it was about power at a time when New York was on the cutting edge of great expansion.

And indeed, the contest between Lawrence and Whig candidate Gulian C. Verplanck was a stand-in for disapproval of Democratic president Andrew Jackson — and his dismantling of the Second Bank of the United States.

In fact the Whig Party was primarily formed in protest to Jackson’s policies. And they would make quite a first impression on their very first election ballot in New York.

A proud New York tradition returned with that first election — rioting. The first electoral process lasted three days, as Democrats and Whigs attacked each other on the street in front of polling places.

On April 8, 1834, men fought with knives and clubs, destroying ballots and virtually shutting down the entire process. One man was killed, twenty others wounded.

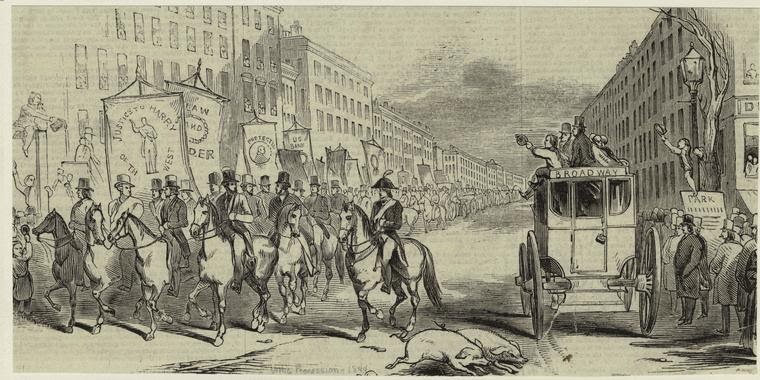

The Whigs were almost war-like in their determination to wrest power from Democrats, actually decorating a frigate with Whig banners, calling it the Constitution, and dragging it up Broadway in a violent and vitriolic parade.

Democrats were no better; the following day, acolytes headed down to Wall Street to destroy a pro-Whig newspaper office, its publisher armed and ready to shoot.

By April 10, the final day of voting, thousands filled the streets, ransacking gun shops and arsenals, preparing for all-out chaos.

“With Armageddon in the office, the mayor called out all troops — twelve hundred infantry and calvarymen — and order was restored,” according to Edwin G Burrows and Mike Wallace. But even that resolution was one-sided; most of the infantry was faithful to President Jackson — and by extension, Lawrence, the Democratic candidate.

With thousands gathered outside City Hall, the election results were announced — Lawrence had defeated the Whig candidate Guilian Verplanck by less than 200 votes!

New Yorkers had at last exercised their direct right to vote for mayor. And in the end — after days of riots and tumult, an election process singular in its chaos — New Yorkers voted in “the crying congressman.”