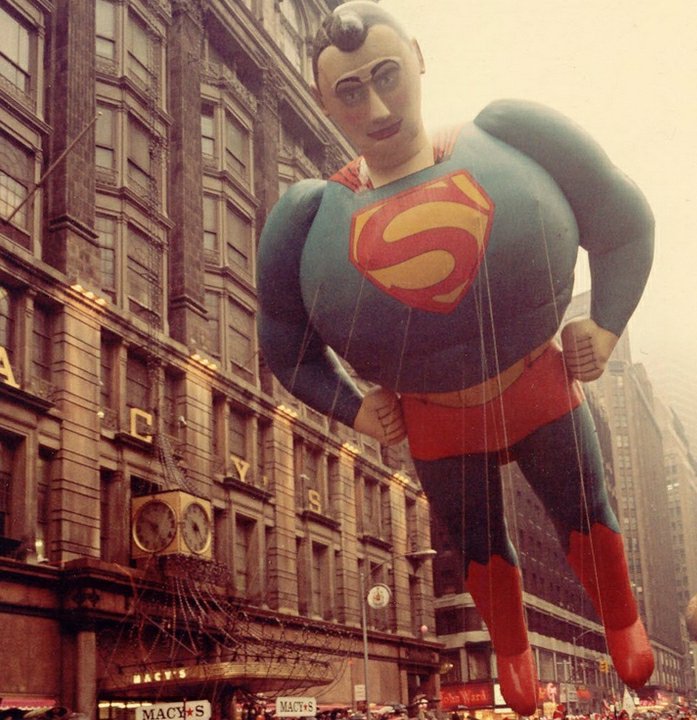

On November 24, 1966, millions of spectators flooded Broadway in New York City to watch the Macy’s Day Parade on Thanksgiving morning.

The iconic floats – Superman, Popeye, Smokey the Bear – were set against a grey sky that can only be described as noxious.

A smog of pollutants was trapped over New York City, and it will ultimately kill nearly 200 people.

How did the 1966 Thanksgiving Smog help usher in a new era of environmental protection?

And how have we been thinking about environmental disasters all wrong?

This episode comes from our friends over at the podcast HISTORY This Week from the History Channel. You can listen to more episodes of HISTORY This Week on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts.

HISTORY This Week: A Toxic Turkey Day

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

NOTE: This transcript may contain errors.

Sally Helm: HISTORY This Week. November 24, 1966. I’m Sally Helm. It’s Thanksgiving Day in New York City, and an awkward, top-heavy Superman balloon is floating down Broadway. He’s first up in the annual Macy’s Day Parade. There are a million people watching in the streets: moms in hats and mittens, kids in checkered coats. There are marching bands. Ballerinas. People waving pom poms in front of a castle on the Toyland float. On the Flower Float is the famous Nina Simone. She sings the song “Blue Skies.” But the skies are not blue in New York City today. They’re gray. The clouds look dirty. And after they leave the parade, the ballerinas and the marching band musicians and the pom-pom-wavers—some of them might feel a tickle in their throat. Their eyes might be stinging. They might even find it hard to breathe. Because while the Macy’s day parade is happening in Midtown Manhattan, the city’s air laboratory up in Harlem is recording extremely high levels of pollution. New Yorkers have dealt with pollution before. But nothing like this. Over this Thanksgiving weekend, the smog will turn deadly. By the time all is said and done, close to 200 people will die. The Killer Smog of 1966 forces New Yorkers, and people all around the country, to finally pay attention to the air pollution that they were actually breathing all the time.

Dr. Uekotter: It’s hard to talk about smog and smoke and air pollution dangerous without reflecting on humans, inability to take chronic threats seriously. There seems to be something about the modern mind that longs for this kind of apocalyptic vision, the big disaster. Rather than the toll that your lungs, your eyes, your body suffers each and every day,

Sally Helm: Today: The apocalyptic vision comes true. How did New York City’s killer Thanksgiving smog help usher in a new era of environmental protection for the whole country? And how are we still looking at environmental disasters all wrong? Professor Frank Uekotter grew up in Germany. But in the 1990s, he came briefly to live in the United States. And he made it out to LA. My wonderful hometown. And also, a notoriously smoggy city. Uekotter has read all about the worst years of smog in the 1950s.

Dr. Uekotter: You couldn’t stand at a street corner in Los Angeles in the early fifties, and not have watering eyes.

Sally Helm: He told us, by the time he was there in the early 1990s, things were much better. No watering eyes. But still, he got curious about air pollution. He began looking into the history of smoke, and also its modern cousin: smog. What is smog?

Dr. Uekotter: This is a term coined by a Londoner. Smog is a combination of smoke and fog, which describes the situation in London very nicely. This is 1904. When the treasurer of the coal smoke abatement society in London, England, a sense of Christmas day letter to the times of London

Sally Helm: And with that, this coal smoke abatement treasurer makes up this word that we still use today. Coal smoke is a problem at this time in London. And in other cities, too. The world is industrializing rapidly. Factories everywhere. And a lot of those factories run on coal combustion. So, if you are living in a city that is becoming a center of industry:

Dr. Uekotter: It was dirty in a way that is barely speak able nowadays because the smoke, it was everywhere in the big cities. It intruded into private quarters. It was literally in the air everywhere. You can actually see it from outside that there was a kind of a dark cloud over the city.

Sally Helm: And people were very much against it. But not so much for health reasons.

Dr. Uekotter: Mostly due to the fact that the early 20th century city was unhealthy on so many fronts. This was ranked as a minor issue.

Sally Helm: You gotta deal with your sewer problems before you deal with your smoke problems. But still, people hated the way that smoke just made everything so dirty and ugly and gross.

Dr. Uekotter: It’s mostly a problem of cleanliness. It’s by extension of problem of property values. It’s not good for real estate values.

Sally Helm: That’s what people are upset about. How this would affect their bottom line. Meanwhile, the particulates that they’re breathing are very bad for their lungs. You may have seen an image of the black lungs of a city dweller compared to the nice pink lungs of someone who grew up in the country. That’s beginning to happen for the first time. But doctors and epidemiologists won’t be aware of this kind of damage for years.

Dr. Uekotter: Over the last, three decades, we have learned a great deal about how dangerous fine dust actually is to the lungs. And we, nowadays, know, that fine dust is actually among the top 10 killers in the world. It’s a bit of an irony of history that we only became aware of how dangerous this is, at a time where it was mostly gone, in the Western world. But retrospectively we must say this was a matter of life and death.

Sally Helm: So, no one is doing all that much about air pollution or smog because it’s not seen as a deadly problem. But there is a very particular set of circumstances in which smog can be lethal.

Dr. Uekotter: Smoke becomes a killer. Particularly when weather conditions impede dispersal of pollute and that’s usually the result of an inversion layer.

Sally Helm: An inversion layer. So, normally, air is warmer close to the earth, and it gets colder as you go up. You may have experienced that if you’ve ever climbed a mountain. You may also know the concept that heat rises. So, typically, warm air is rising up from the earth, getting colder as it goes up, and dispersing and flowing and moving around. But sometimes, this whole situation gets reversed. Warm air slips on top of cold air. The cold air doesn’t rise. So, it’s trapped. The warm air acts like a lid.

Dr. Uekotter: That basically traps pollutants. In the place and near the place where they are produced and, causes them to accumulate, in the atmosphere.

Sally Helm: When this happens, pollutants build up and smog can become deadly. In the US, the first major case of smog happens in July of 1943.

[ARCHIVAL]

Sally Helm: LA up until the 40s had been known for its clean air. If you had tuberculosis, you went to LA to breathe those California breezes and clear out your lungs. But now…

Dr. Uekotter: 1943 is when the first LA smoke episode comes and you had watering eyes, you had breathing problems.

Sally Helm: Visibility is terrible. The air smells like bleach. And it all comes on suddenly, on July 26th.

Dr. Uekotter: Nobody really knows what it is. What is the pollutant? Where does it come from?

Sally Helm: It’s World War 2, so people actually think it might be a Japanese gas attack. And this smog is different from London smog–it’s not really about smoke. It’s photochemical smog, where pollutants from car exhaust and factory production cause a chemical reaction in the atmosphere. That creates this particular LA smog. Plus, LA is prone to inversions because of its topography, it’s bordered by mountains. But people won’t figure all this out for almost a decade. The science just isn’t there yet. Thankfully, in 1943, no one in LA dies from the smog. But five years later, in 1948:

Dr. Uekotter: Donora, Pennsylvania was the biggest air pollution disaster until New York city in ‘66. This is an industrial community around a river Valley.

[ARCHIVAL]

Sally Helm: The valley where Donora sits is ripe for inversions, and there are steel mills and zinc plants in the area spewing off pollutants. On Halloween in 1948, pollutants get so concentrated that the local fire brigade has to go door-to-door giving people oxygen. Twenty people die. It’s the deadliest toll per capita of any smog episode before or since. And this gets national attention.

Dr. Uekotter: These major events do, at least pollution gets noticed. What happens in Donora is that the federal medical authority is asked to investigate, well, what happened here?

Sally Helm: The investigators link the pollution and deaths to noxious fumes coming from the local factories. There are a few lawsuits…

Dr. Uekotter: But that’s about it. There was no legislation, the warning system, this is a factory town, and the factory is calling the shots. Of course, the factory makes sure that, next time there is an aversion, there are a bit more careful, you know, factories don’t want to kill their neighbors.

Sally Helm: But there are no real consequences for the factories. There is also very little in the way of a national or a global effort toprevent disasters like this from happening again. And one does happen again, in London. Which, remember, had invented the term smog in 1904. But since that era, they had kind of gotten off scott-free.

Dr. Uekotter: The best guess is maybe they were just lucky for a few decades, but then this returns, in, late 1952.

Sally Helm: This will be the deadliest smog ever. It also came from an inversion that trapped pollutants released by factories and by city residents. Epidemiologist Devra Davis wrote that in London, quote “smoke ran like tap water from a million chimneys.”

[ARCHIVAL]

Sally Helm: The killer smog lasts for months. Thousands of people die. Though, it takes a while to untangle just how many.

Dr. Uekotter: If people die from smoke, it’s not like they’re die immediately. There was no kind of imminent cause that he can identify. But it’s a burden on the respiratory system that may get a heart attack. They may get breathing problems, emphysema. The best estimates that we have suggests that 12,000 people died prematurely during that smog episode of 1952.

Sally Helm: And in this case, there is some regulation. Four years after this killer smog, Britain passes a big law about clean air. Though Dr. Uekotter says, activism had been happening even before the big smog.So, the reality isthat this flashy moment of action after a disaster was just one piece of a larger puzzle. Which brings us to New York. And the United States’ last killer smog. Because of a slow drip of activism and reform and scientific progress, New York wasn’t totally unprepared for something like this. By 1966, meteorologists can sort of predict inversions. And there are some regional pollution monitoring systems. In fact, right before this smog event happens, the US Senate Committee on Public Works puts out this video.

[ARCHIVAL]

Sally Helm: So, officials are beginning to understand what they’re up against. But in New York City, the infrastructure still isn’t ready for the disaster that is about to strike. There’s a city department of air pollution control, but they only control things up to the city limits. There’s an interstate sanitation commission, but they’re mostly focusing on water.

Dr. Uekotter: So, any kind of framework that you need for a comprehensive drive against pollution, it’s just not there.

Sally Helm: New York city does have a smog alert system and a way to monitor and measure pollution. There’s one lab in an old courthouse in Harlem. And a few days before Thanksgiving, it starts recording elevated levels of air pollution.

Dr. Uekotter: It’s a combination of the everyday pollution in New York City. There’s the garbage, there is the car traffic. There is the factories. There is the power plants, and there is a weather situation that traps these pollutions close to the ground.

Sally Helm: An inversion. All this combines to create a deadly smog bubble over New York City, the day before a million people are about to flood the streets…

[AD BREAK]

Sally Helm: One of the first people to be notified about the high air pollution readings in New York is a man named Austin Heller. He’s the city commissioner of air pollution control. And he has to decide whether to declare a smog alert.

Dr. Uekotter: There is a set threshold that people look at very closely, but it’s a decision that is taken, cautiously. Shutting down a city, is no small measure.

Sally Helm: Plus, it’s Thanksgiving. The Macy’s Day parade is a national spectacle. People are expecting the show to go on.

Dr. Uekotter: As an added complication, the mayor of New York city is not in town. He’s vacationing, in Bermuda. So, he’s far away, and, the city ministration is, is pondering this big decision.

Sally Helm: Heller talks to the Deputy Mayor, various medical experts and scientists and decides, the levels are just low enough, that the parade can go on as scheduled. They do take some precautions – Heller spends Wednesday on the phone with Con Edison, the city’s fuel provider, and gets them to switch temporarily from fuel oil to cleaner natural gas. All the city-owned garbage incinerators get turned off. Garbage incineration is a huge source of pollution. But still: New Yorkers are starting to notice that something is off.

Dr. Uekotter: It becomes, a bodily phenomenon. People can actually feel, they breathe it whenever they go outside or even breathe it in their own homes.

[ARCHIVAL]

Sally Helm: On Thanksgiving Day, a million parade-goers–plus dancers and tuba players and people holding the strings of giant Superman balloons–they all come out for the Macy’s Day parade. And as the day goes by, the air quality gets worse. That night, Commissioner Heller calls inspectors away from their Thanksgiving dinners to go around the city and try to crack down on any pollution violations. And around 1 am, the city finally issues a smog alert.

Dr. Uekotter: Nothing meta really happens but it is a warning that is issued. People are encouraged to switch off their garbage incinerators.

Sally Helm: Some hospitals are reporting increased numbers of patients coming in with asthma and other lung problems. Eye doctors tell people not to wear their contact lenses outside. An allergist says that kids under two should stay at home. The New York Times reports a sight that, in the age of coronavirus, is totally commonplace, but in that moment, it was novel: a woman was walking through Midtown Manhattan in a surgical mask. On Saturday, finally, the weather changes.

Dr. Uekotter: There’s a cold front coming that ends this, abnormal aversion layer. And finally, the dirty air can disperse.

Sally Helm: In the end, a task force calculates that the death toll from the smog was 168 people. So, not nearly as high the London Smog or as deadly per capita as the Donora smog. But this happens in a major US city during a major holiday. It gets a ton of press coverage. And by this point, 1966, the dangers of air pollution are better understood. So, it’s becoming clear to the public that the current approach to pollution just isn’t working.

Dr. Uekotter: It’s very much every city, every state defining its own system and often under the control of powerful industries.

Sally Helm: In New York, there’s pretty quick action at the city level. They strengthen the pollution guidelines in the city Administrative Code. That lab in Harlem gets an upgrade, and the city announces that they plan to open 36 more locations to monitor air quality. They buy a fancy new computer system so that all those labs can communicate with each other. But…it’s still just local.

Dr. Uekotter: You need tougher action. You need action that retargets entire regions or the entire nation.

Sally Helm: President Lyndon Johnson is also under pressure. He sends a message to Congress in which he talks at length about the New York Smog of 1966. He says the country needs legislative action. And in 1967, he gets it. He signs the Clean Air Act into law. But it ends up not being that effective–a lot of regulation was still left up to the states, and some of them didn’t do all that much. A few years later, in a Supreme Court decision, Chief Justice Rhenquist calls state response to the law quote “disappointing.” But in 1970, under the Nixon administration, a new version of the Clean Air Act passes. And it moves pollution protections more fully under the control of the federal government:

Dr. Uekotter: So, it’s a shift from a patchwork of local and state regulations towards, let’s say, halfway uniform national approach to pollution problems.

Sally Helm: The Environmental Protection Agency, the EPA, is founded in December of the same year. Among other things, it helps implement the requirements of the Clean Air Act. And finally–almost 70 years after the term was coined across the pond–smog in the US starts to significantly decrease. There are a lot of things that led to this big moment of environmental action in 1970. But one of them is this flashpoint in 1966. When smog was so visible, and deadly. A lot of people watched the Macy’s Day parade on TV. A lot more people read about it. And that helped spur action.

Dr. Uekotter: What do you realize is what captures the public imagination is the disaster, the acute episode. Something you can see, something you can respond to directly and something that you can quantify in precise numbers, something that is very important to the soul of modern people.

Sally Helm: Dr. Uekotter reminded us over and over: the story that one big disaster spurs one big law that fixes everything–That just isn’t right. After 1970, there are still lots of court battles and wrangling back and forth over these regulations. Scientific progress plays a big role in bringing air pollution down, and that takes time. And the regulation that we’ve been talking about is mostly in the US–there are other cities around the world that continue to have major smog problems up to the present day. Solutions just don’t come all at once.

Dr. Uekotter: There’s always this kind of consulting narrative, that comes into place with each disaster. Now we will learn from this disaster. No, it’s more, um, disasters are really more like it opens political opportunities for some time, but the moment passes well sooner than you wish. We are forgetful people when it comes to these disasters, and we should be wary about these kinds of smooth narratives. You have learned our lesson. There is no silver bullet for any of these pollution problems anymore.

Sally Helm: Thanks for listening to History This Week. For more moments throughout history that are also worth watching, check your local TV listings to find out what’s on the History Channel today. And for HISTORY anytime, anywhere, sign up for a 7-day free trial of HISTORY Vault. Where you can stream over 2000 award winning documentaries and series from your favorite device with new videos added every week. To start your free trial visit HistoryVault.com/podcasttoday. This episode was produced by McCamey Lynn. History This Week is also produced by Julie Magruder, Ben Dickstein, Julia Press, and me, Sally Helm. Our researcher is Emma Fredericks. Our executive producers are Jessie Katz and Ted Butler. Don’t forget to subscribe, rate and review History This Week wherever you get your podcasts, and we will see you next week.