Frances Ethel Gumm was born 100 years ago (June 10, 1922) in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, a world away from the glamour of Hollywood and the lights of Broadway. Yet — as Judy Garland — she would change both places forever, becoming one of the most beloved entertainers in the world.

And she remains beloved to this day — by international fans of her films The Wizard of Oz, A Star Is Born and Meet Me In St. Louis, by music lovers entranced by her rich, emotional voice, by many members of the LGBT+ community who still exalt her as a pop culture legend.

Unlike California, New York was never really her home in the same way — although she did have an apartment here in the 1960s. New York City always knew Judy as a star and revitalized her career at a critical moment.

And she loved the city for that reason. “I’m always at my best in New York.” she once claimed. And when she was not her very best — which was not uncommon — her New York fans stood by her.

Here’s a look at Judy Garland’s New York, the places and spaces which made her an icon.

A Star Is Born

Garland hit the ground running on her very first trip to New York in 1936 — already an MGM star at age 14 — heading to Decca Records West 57th Street studio to record her very first record — “Stompin’ At The Savoy,” originally made famous by Benny Goodman. (Interestingly she would not actually step foot in Harlem’s Savoy until many. years later.)

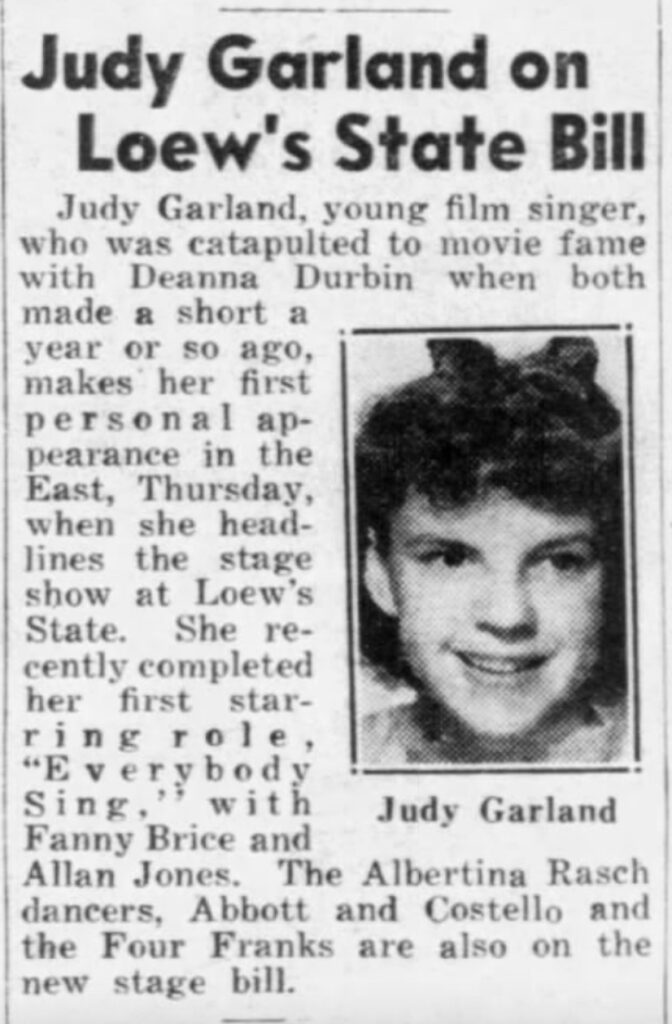

Two years later, in 1938, Garland would make her first stage appearance in New York City at the Loew’s State Theater, the Thomas Lamb-designed movie palace at 1540 Broadway that was still booking vaudeville acts into the 1930s.

Garland was there to promote her film Everybody Sings, a forgettable film co-starring Fanny Brice. But her appearances during the hectic promotional tour — a miniature singing and dancing sensation — dazzled audiences, a true ‘star is born’ moment which set her career in motion.

By the time she returned to the Loews State in the spring of 1939, she was already a mega-star thanks to the hit film Love Finds Andy Hardy, her second on-screen appearance with Mickey Rooney.

On April 10, 1939 she was quite literally whisked around town on a cyclone-like tour of Loew’s theaters:

While at the Loews Triboro (2804 Steinway Street in Astoria) she obviously lost a hat. Garland offers a reward to New Yorkers for the accessory that went missing in Queens (April 13, 1939).

Off To See The Wizard

Her next visit to New York is considered by some to be a legendary moment in American entertainment history.

Garland was swinging through town on another frantic tour with Rooney. But this time they were promoting her big star-making vehicle.

The pair arrived at Grand Central Terminal on August 14, 1939 to thousands of well-wishers. (You can see footage of Garland and Rooney at the train station in this video.)

Three days later, on August 17, the film The Wizard of Oz premiered at the Capitol Theater (1645 Broadway), and Garland and Rooney were there, performing live, five shows a day, between sold-out screenings. (On the weekends, they did seven performances a day.)

They were constantly on the go in New York, an exhausting blur of public appearances. And everywhere they went, adoring crowds met them — at restaurants, on the street, at the Waldorf-Astoria, even at a brief appearance at Madison Square Garden.

But the duo’s most interesting stop was to Flushing-Meadows Park in Queens — hopefully Judy left her hat at home — for the 1939 World’s Fair where they met Mayor Fiorello La Guardia:

Rooney and La Guardia shared some corny banter:

Rooney: “Mr. Mayor, I have a lot of friends out on the coast and elsewhere who would like to come to your wonderful fair. Is there any place they can stay besides expensive Park Avenue hotels?”

La Guardia: “Why, Mickey, New York is just like any other city in the country. The only difference is that we have 50,000 places for people who visit the Fair to stay as low as 50 and 75 cents, and we have better food for less money.”

Judy and Mickey then spent the day enjoying the many rides at the fair including the Parachute Jump — the very same amusement which new sits in Coney Island today.

Rooney then left town and Garland returned to the Capitol Theater — but she wasn’t alone.

She was joined by a couple of her Wizard of Oz costars, men who were familiar to New York vaudeville audiences — Bert Lahr and Ray Bolger. Imagine seeing them live — then seeing Oz for the very first time — for just a quarter.

Meet Me In New York

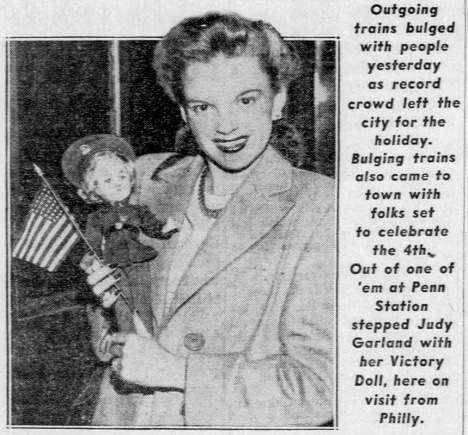

Her rigorous filming and recording schedule in Los Angeles meant long, intense days at the studio — and little traveling. But she appeared briefly in New York in 1943 as part of a USO tour, entertaining troops heading to war. Here’s Garland at Penn Station in August of 1943:

Her next companion in New York was neither Andy Rooney nor a victory doll.

During Thanksgiving week in 1944, Garland arrived with director Vincente Minnelli for the premiere of Meet Me In St. Louis at the Astor Theater (1537 Broadway,). While in New York, they announced their engagement to the press.

The New York Times gifted the film with a rapturous review: “Let those who would savor their enjoyment of innocent family merriment with the fragrance of dried-rose petals and who would revel in girlish rhapsodies make a bee-line right down to the Astor.”

In 1945, Garland and Minnelli honeymooned in New York for three months. Even then she continually recorded music and made radio appearances — all the while pregnant with Liza May (born March 12, 1946).

By the late 1940s Garland’s non-stop (and abusive) schedule had taken a serious toll on her in Los Angeles. Even as her problems began seeping into the press, her supporters came to the rescue.

On September 1, 1950, the New York Daily News published a column from theater impresario Billy Rose titled “Love Letter to a National Asset,” both an adoring fan letter and a pep talk. Rose probably knew Garland through his former wife Fanny Brice but here he scribbles down a gushing tribute:

“It gets down to this Judy: In an oblique and daffy sort of way, you are as much a national asset as our coal reserves — both of you help warm up our insides.“

An excerpt from the Daily News (with an accompanying illustration):

Queen Of The Palace

But the most important date in Judy Garland’s New York life was October 16, 1951 — her first performance at the Palace Theater. Her scheduled four-week run stretched to a record nineteen weeks, becoming one of the most legendary theatrical runs in New York history.

The Palace (at 1564 Broadway) first opened in 1913 as a straight vaudeville house but it was a 1915 appearance by acclaimed French actress Sarah Bernhardt put the venue on the map. But by the 1930s, like so many Broadway theaters, it had become a movie palace.

Garland’s live appearance was an attempt to reintroduce vaudeville at the Palace. While that certainly did not happen, Garland’s shows became the true stuff of legend.

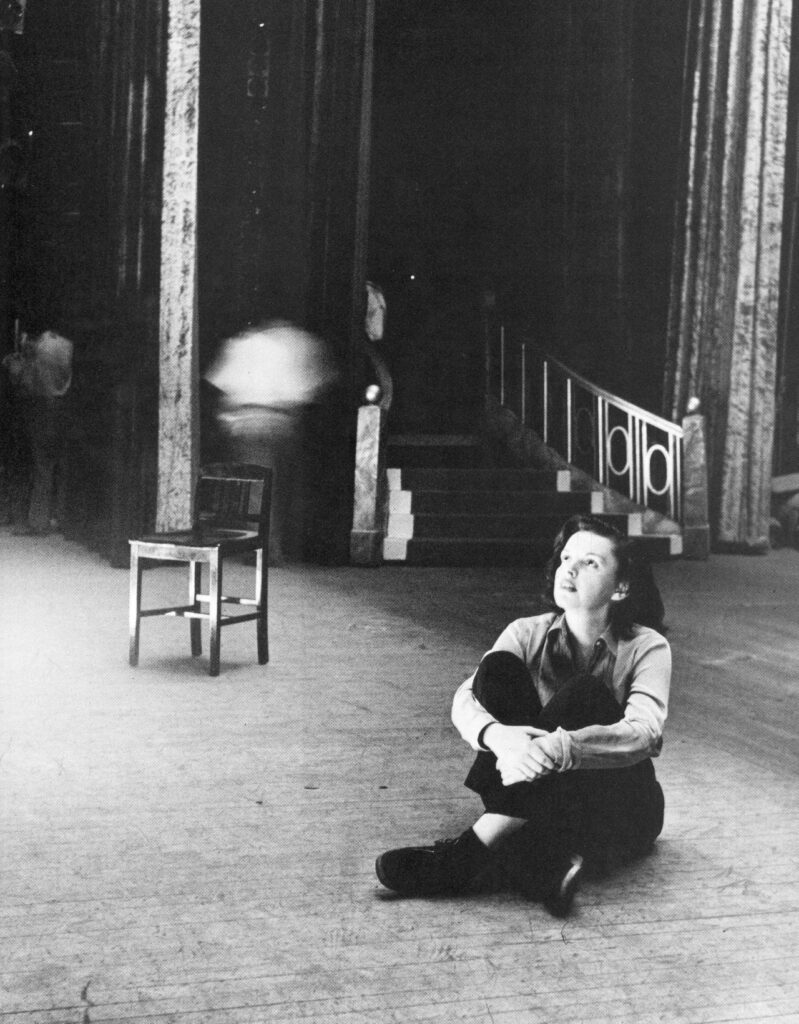

Garland in rehearsals at the Palace, 1951

“Never in this reporter’s memory has there been such a furor outside and inside a single theatre,” writes Robert Sylvester for the Daily News:

“Outside Broadway and 47th Street was blocked off by sawhorses and harassed cops managed to keep thousands of gawkers on the safe side of the blockades. Inside, the explosion of applause which greeted Miss Garland’s entrance threatened to get complete out of hand. The enfant terrible of the musical films finally hollered it down herself and then went on to do one of the most fantastic one-hour solo performances in theatrical history.“

According to Life Magazine: “Almost everyone in theater was crying and for days afterwards people around Broadway talked as if they beheld a miracle. What they beheld was Judy Garland making her debut at the old Palace, which was having a comeback to straight vaudeville. But the real comeback was Judy’s.”

Although this revitalized Garland’s career at a time when her film career was tanking, it also put the superstar through another grueling schedule which facilitated her reliance on alcohol and drugs.

C’mon Get Happy

The Palace would open its doors to her again — next in 1956 for the show Judy Garland in Person. Making her stage debut at the Palace was her ten-year-old daughter Liza who would go on to many Palace performances of her own.

But Judy also performed in other New York City venues over the years. Here’s a list of the most notable:

— The Town and Country Club in Flatbush Brooklyn, was notable for Garland opening (on March 20, 1958) to a sold-out house — during a massive snowstorm. Due to various delays, Garland began performing at midnight.

Ten days into her engagement, she was fired.

To quote from the glorious website The Judy Room:

“ Judy only got through the first two songs of her act when she announced that she had laryngitis and had been fired, then left the stage. She had developed severe colitis before opening but had been able to get through the shows until this night. The newspapers reported that she had been an hour late for the show and that the club’s manager, Ben Maksik, noted that when she showed up she was obviously sick. Maksik also said he advanced Judy $40,000, which Judy denied.“

— The Metropolitan Opera House — Garland’s performances here in 1959 — one of the first by a non-opera performer — benefited the Children’s Asthma Research Institute and Hospital.

During this period, Garland was often very ill in part due to her reliance on alcohol and pills. In 1959, she was admitted into Doctor’s Hospital (formerly at 170 East End Avenue). As James Kaplan wrote in Vanity Fair, “With a quarter-century of hard living behind her, [Garland] lay near death in New York’s Doctors Hospital. Alcohol and pills were the culprits. “

Below: Liza with her mother following a hospital visit

The Swinging 60s

In the last decade of her life, Garland, weakened and exhausted, still gave the audience her all. And she provided New Yorkers with some magnificent music moments.

— The Copacabana — Her appearance at this legendary nightclub in January 1961 wasn’t an official performance but I bet it was memorable. She popped up on stage during Sammy Davis Jr. final night of his legendary run of shows here and did an impromptu version of “Over The Rainbow.”

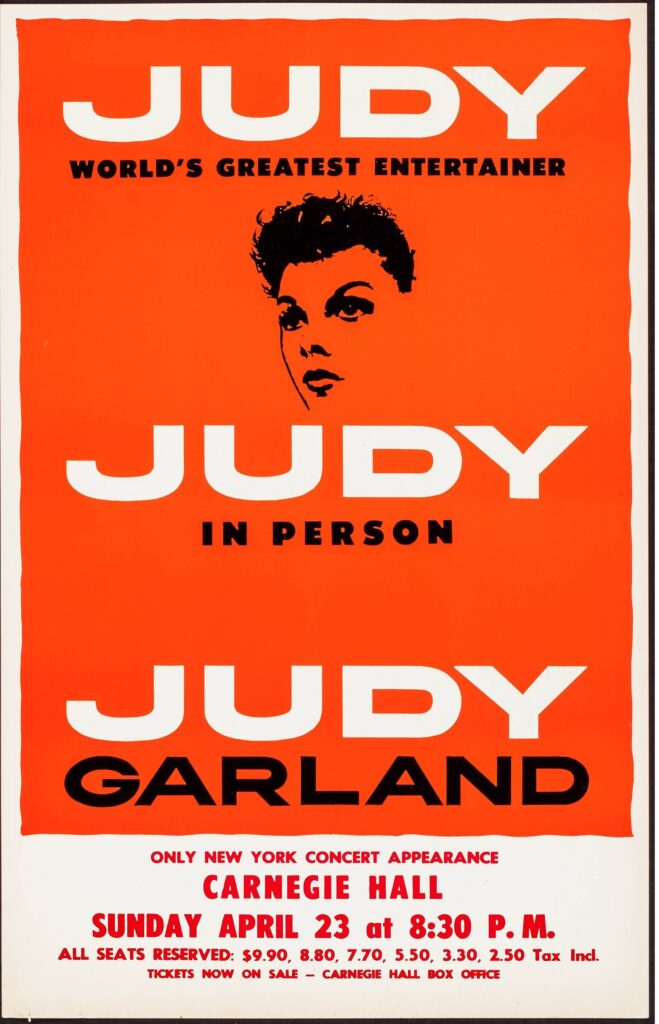

— Carnegie Hall April 23 and May 21, 1961 Her first appearance here is probably Garland’s best known stage performance because it was recorded and released as Judy at Carnegie Hall, an album which spent 95 weeks on the Billboard Charts.

— Manhattan Center 1962 Among the luminaries who witnessed Judy’s performance here in 1962 were Marilyn Monroe and a rising young songstress named Barbra Streisand. She had a bad case of laryngitis that night and Capitol Records scrapped plans for a live album. (In 1989 the album was finally released — Judy Garland Live!)

— Forest Hills Stadium She performed two times at the classic tennis-club-turned-performance venue in July 1961, but it was her show here four years later (on July 17, 1965) that made headlines for the 10,000 audience members who gave her allegedly the “longest standing ovation” for a performer at that time.

Before stepping on the stage, Judy told the press: “New York is my town and I’m really looking forward to this concert. I’m always at my best in New York.”

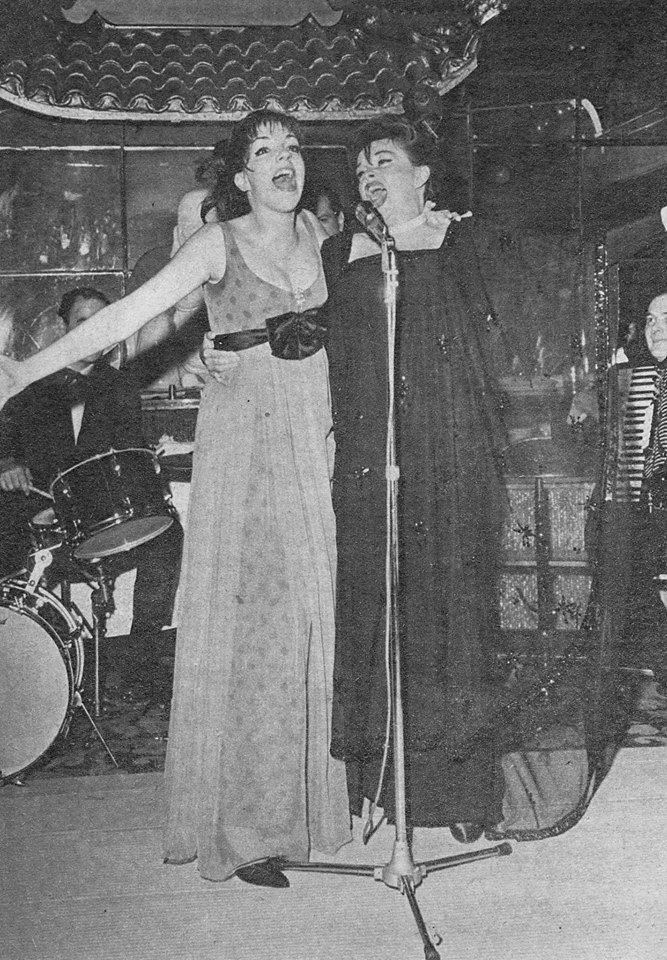

— Ruby’s Foos May 11, 1965 — Not a music venue but oh want a performance to have seen! Judy and her daughter Liza performed together at this classic Chinese restaurant in Midtown at an afterparty for Liza’s Broadway debut in the play Flora the Red Menace:

She performed a final run of shows at the Palace Theater from July 31 to August 26, 1967. The shows were greeted with the same enthusiasm as her previous appearances. Jerry Tallmer from the New York Post gushed, “Judy, for the thousand and first time, has come all the way back.”

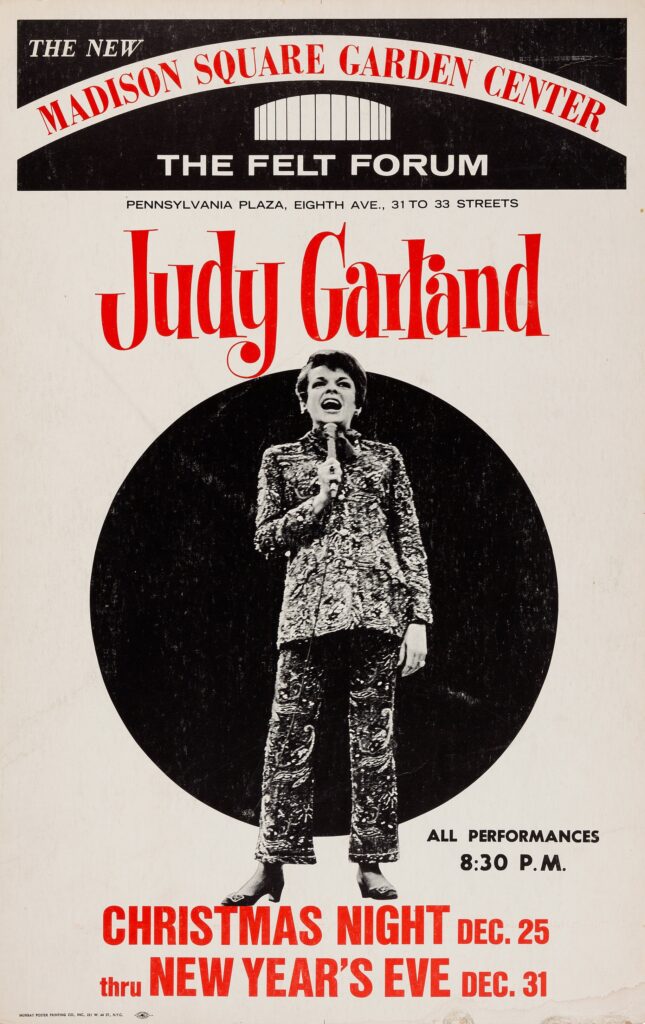

In 1967 she also played Madison Square Garden, one of the first shows at venue’s new Felt Forum (today’s Hulu Theater at Madison Square Garden) above the new subterranean Pennsylvania Station. During the show she was joined by Tony Bennett for a couple Christmas numbers. She did not complete her run of shows, cancelling after her final appearance here on December 27.

There No Place Like Home

Garland lived in several cities over the years — in the Hollywood Hills, Malibu and London — although in a way, it’s hard to associate her with any place on the map. (Of course, for many, she’ll always be that girl from Kansas or St. Louis.)

While in New York, she mostly she lived in hotels, of the most glamorous sort — the St. Regis, the Carlyle, the Regency, the Plaza, the Sherry Netherland. In 1961 she even lived briefly at the Dakota Apartments.

In 1968 she was locked out of the St. Moritz Hotel (50 Central Park South) for not paying her bills.

The Rainbow

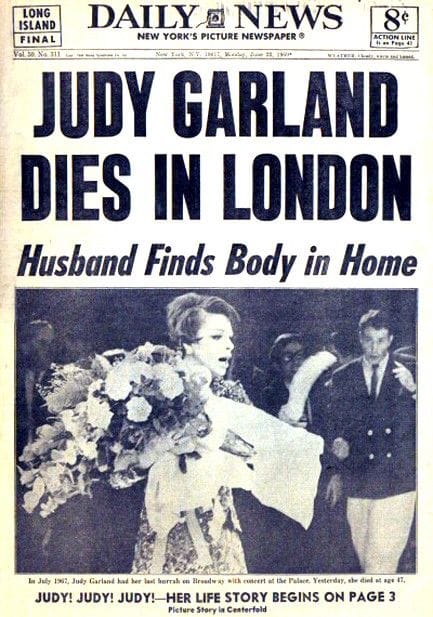

On June 22, 1969, Garland was found dead in her rented house in London. She was 47 years old. The cause of death was an accidental barbiturate overdose.

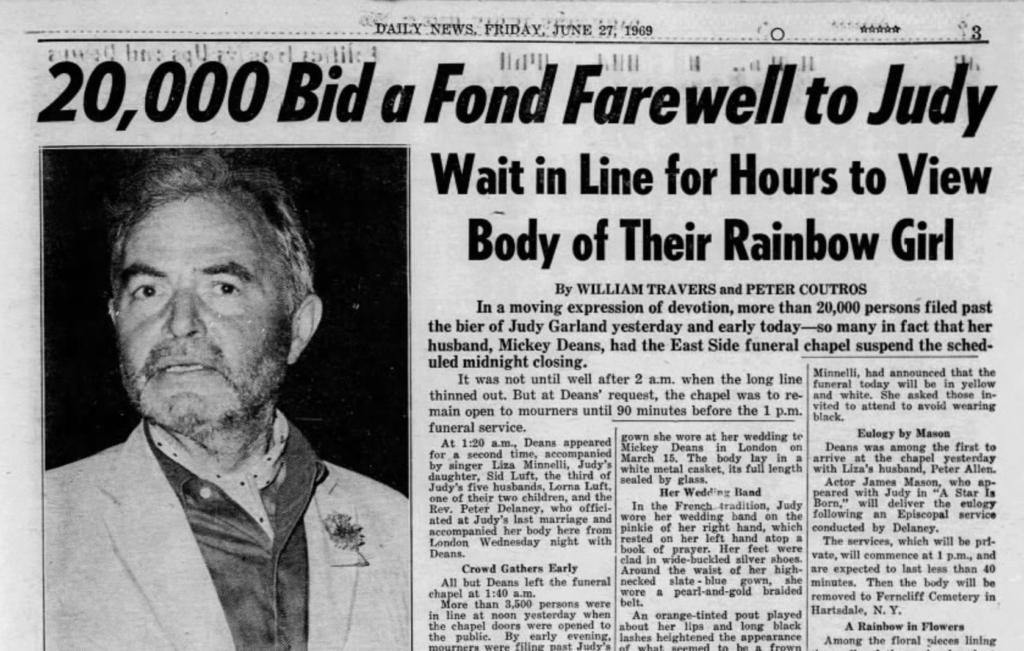

The world mourned her passing — and most especially, we can assume, her legion of fans in New York City. Her funeral at Frank E. Campbell’s Funeral Chapel drew thousands of mourners who gathered along the surrounding streets.

From the New York Times: “While legions of her fans maintained an ardent vigil in the hot and humid streets, colleagues of Judy Garland bade her farewell yesterday in a swift, simple service at the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Home.

“Judy’s great gift,” James Mason said in his eulogy, “was that she could wring tears out of hearts of rock.”

Although the press was barred from the actual service, portions of the funeral, including Mr. Mason’s eulogy, were audible through a loudspeaker provided by Campbell’s in an upstairs room.”

Many hours later in the West Village, in the early morning hours of June 28, police raided a gay bar named the Stonewall Inn. The patrons, tired of the homophobia and the cycles of police intimidation, at last fought back.

As many of Judy Garland’s most passionate fans were gay, could this mean that her death, as urban legend goes, fueled the passions that went into the historic event today known as the Stonewall Uprising?

It’s impossible to really say. The people at the Stonewall Inn that first night of conflict were probably younger than the average Judy Garland fan. However, in the following days, as more people gathered on the streets of the West Village to protest, it’s very likely that many who attended Garland’s funeral were also there — at the dawn of the Gay Liberation Movement. (Listen to our Stonewall Riots show for more information.)

Everybody Rise

Today the Palace Theatre, the greatest landmark to Garland’s New York legacy is getting a facelift. Scratch that, an UP-lift.

The theater has literally been lifted 30 feet off the ground as part of a massive new construction project, a 46-story, 661-room hotel being built above it.

According to the New York Times: “L&L Holding, the lead developer on the TSX project, made arrangements with the theater’s owner, the Nederlander Organization, to elevate the Palace and fill the void with three floors of new shopping space, part of 10 floors of retail in the tower. The theater will have a new entrance on West 47th as well as a new lobby, marquee and backstage area.”

By the way, does Judy Garland still haunt the Palace Theatre? That urban legend is explored in our podcast Haunted Histories of New York.

3 replies on “The Ultimate Guide to Judy Garland’s New York: From the World’s Fair to the Palace Theatre”

I love in depth biographies like this. Judy Garland was an excellent story, filled with awesome details & pics. Thank you!! 👍👍

Forever Judy. Great job. Hope to see an episode on this soon!

Thanks for the great shout-out to The Judy Room site. I appreciate it! And what a fun article. I love the clippings.

Judy’s time in New York encompassed most of her career and goes back earlier than I think most people would assume.

Happy Holidays!