Journalists Harold Ross and Jane Grant founded the New Yorker magazine in 1925, but another weekly journal with that same name debuted on the streets of the city over 90 years earlier. It was a short-lived publication, existing not more than a few years, but it helped sharpen the talents of its young publisher, Horace Greeley.

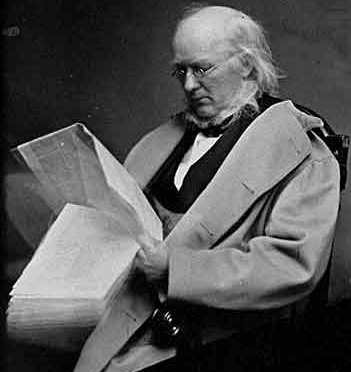

At age 23, Greeley (at right) embarked on the venture on March 1834 with a rather modern objective — to be politically neutral. (Don’t they all start out that way?) And studious in its presentation, to the letter. “If there is a thing that will make Horace furious,” according to one of his proof-readers, “It is to have a name spelt wrong, or a mistake in election returns.”

At age 23, Greeley (at right) embarked on the venture on March 1834 with a rather modern objective — to be politically neutral. (Don’t they all start out that way?) And studious in its presentation, to the letter. “If there is a thing that will make Horace furious,” according to one of his proof-readers, “It is to have a name spelt wrong, or a mistake in election returns.”

Despite that, Greeley’s New Yorker was a very traditional publication, exhibiting none of the zest of the penny press, rows of staid columns of text, formal headlines and a very austere masthead. (You can read one volume of articles here.)

Greeley often supplemented the journal’s reporting with his own poetry. Eventually, objectivity went out the window as his views on such topics as capital punishment and slavery were soon made clear to readers, but the paper would never exhibit the type of showy grandstanding of Benjamin Day’s far more successful New York Sun newspaper, started just the year before.

From an early biography of Greeley: “Were Greeley and Co. making their fortune meanwhile? Far from it. To edit a paper well is one thing; to make it pay as a business is another.”

The journal only lasted for a few years, and by 1841, Greeley was off on a more exciting, a more opinionated and a far more profitable venture — the New York Tribune.

But on top of giving Greeley a fledgling publication for him to cut his teeth on, the first New Yorker also gave American journalism another prominent figure: young Henry Jarvis Raymond, one of Greeley’s reporters who later went on (in 1851) to found the New York Times.