A ticking bomb goes off at Grand Central Terminal.

The seats at Radio City Music Hall, rigged with explosive devices planted inside the upholstery. Bombs found at the Empire State Building, others detonating at movie theaters and in phone booths, at the New York Public Library and in subway stations. An explosion inside Macy’s.

Chaos, panic, anonymous letters to the police, copycat bombers. Some of the most sustained levels of domestic terrorism to hit an American city in the 20th century.

It may sound like the plot of a dastardly comic book film. But it actually happened in New York City.

The man in the center, the one who looks like a kind grocer? That’s George Metesky, the insane “Mad Bomber” who terrorized New York for years with crudely made bombs placed in public places. (Photo by Peter Stackpole)

Through two decades, from 1940 to the mid 1950s, the city was under siege by a violent, greatly disturbed ex-Marine dubbed the Mad Bomber by the press.

George Metesky planted dozens of pipe bombs in New York City before he was finally apprehended in January 1957 at his home in Waterbury, Conn. He sheepishly met his captors at the door with the phrase, “I know why you fellows are here. You think I’m the Mad Bomber.”

Metesky’s beef wasn’t with the city per se, but with his former employer Consolidated Edison. (Or more exactly, the United Electric Light and Power Company, which was later absorbed by Con Ed.) For a time, his rage was specifically focused at the corporation he believed treated him with extraordinary indifference.

George had been employed by the utility company until 1931, when a boiler explosion at uptown Manhattan plant left him permanently disabled and in the care of his two sisters in Connecticut.

He claimed the company refused to compensate him for his work-related hardship, fighting in vain with the corporation for five years. “My medical bills and care have cost thousands — I did not get a single penny for a lifetime of misery and suffering,” he would claim in one of his many letters to the press, after the bombings began.

For Con Ed’s part, they claimed Metesky had taken too long to file for disability benefits. Eventually, the truth didn’t matter. Metesky, later to be diagnosed a paranoid schizophrenic, decided to get comeuppance in a more sinister manner.

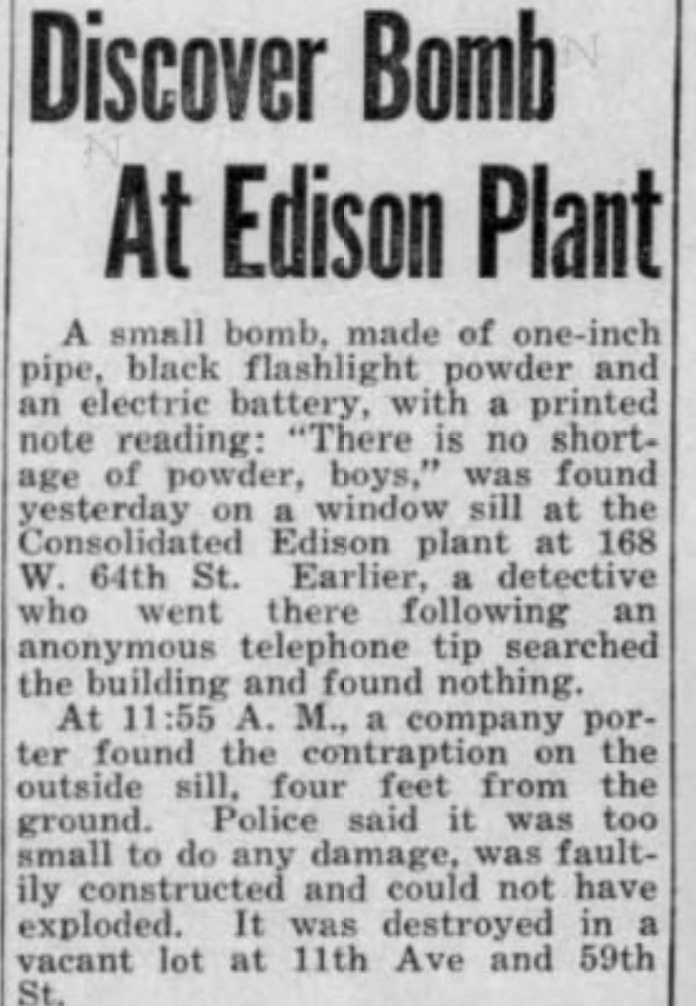

The first explosive, ultimately a dud (as many were), was placed at Con Ed’s 64th Street office on November 18th, 1940, accompanied by a carefully constructed note, “CON EDISON CROOKS, THIS IS FOR YOU.”

One year later, another device, wrapped in a woolen sock, was hastily dropped in front of Con Ed’s 19th Street offices, without a missive this time. In both cases, investigators were befuddled: were the bombs even meant to go off or was it a scare tactic?

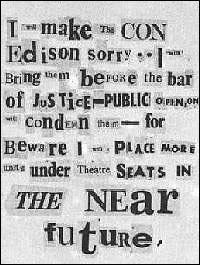

Metesky was feeling ignored yet again by Con Ed. Whether out of frustration or some kind of twisted, legitimate patriotic duty, however, he decided to call off future bombings due to World War II and sent a ‘kidnapper-style’ note (left, one such example), made from cut newspaper letters, to the press informing them so.

Feeling some acceptable amount of time had passed, Metesky decided on a different tactic on March 29th, 1950, planting a bomb at crowded Grand Central Terminal. Another note from George warned of an explosion there, and police were able to locate and defuse the device in time.

Thus began a bizarre game of cat-and-mouse as Metesky laid dozens of bombs throughout the city, unbelievably without detection. (The “see something, say something” mantra was clearly not in effect in the 1950s.)

A fourth device, in front of the New York Public Library, was the first to actually detonate, but it injured no one, the fortunate outcome of many of Metesky’s oddly made devices.

Despite dropping off pipe bombs in such places as Penn Station and the Port Authority Bus Terminal, despite targeting movie houses by scooping out the seats and implanting bombs there — despite some of these weapons actually exploding, nobody had been hurt. He had even thrown a pipe bomb into the Oyster Bar at Grand Central Terminal, with no serious harm.

His devices in 1954, however, began to hurt people — minor injuries in a detonation at a Grand Central men’s room, then during a November screening of White Christmas at Radio City Music hall, where five people were hurt. (You can find pictures of the aftermath of one such bombing at Radio City in this Life Magazine article.) Amazingly, Metesky set off three bombs in total at Radio City. Once, a bomb went off with the bomber still in the theater; an usher stopped him as he was escaping but merely “apologized for the disturbance” and let him go.

He also sent a series of letters to the New York Herald Tribune, all in that same exact block-letter styling. Stating in these letters that he was seriously disturbed, George apologized for any potential injuries he might cause but proclaimed, “IT CANNOT BE HELPED—FOR JUSTICE WILL BE SERVED.” Metesky would sign his letters F.P., which investigators would later learn meant ‘Fair Play.’

Two explosions in 1956 ramped up the intensity and urgency of stopping Metesky. One device planted in a Penn Station bathroom seriously injured an elderly attendant. And Metesky left a Christmastime bomb in the Paramount Theatre in Brooklyn that detonated and injured six people, three seriously. (The film playing? War and Peace with Audrey Hepburn.)

The police were frantically piecing together a profile of Metesky, and dozens of people were apprehended and questioned, including one man who frequently drove into the city with a suspicious trunk in his backseat. It was not Metesky; the trunk contained a pair of sexy fetish boots that the man paid prostitutes to wear.

During this time, dozens of bomb scares were called in throughout the city and there were even other copycat bombers like Frederick Eberhardt who sent a ‘sugar bomb‘ in the mail to Con Edison. He too was a former employee….and mentally disturbed.

It’s a bit difficult to get a grasp on the true on-the-street reaction to these bombings, which were numerous but rarely deadly. Slight panic may have passed through the thoughts of commuters passing through Grand Central or riding the subway, but over time, most people seem to have dismissed the danger. These events are sometimes brought up in comparison to the Son of Sam killings of the 1970s, which held the city in a far greater hysteria.

But, as they’re well equipped to do, the newspapers kept reminding New Yorkers of the danger. According to a 1957 Time Magazine article: “Hearst’s Journal-American thoughtfully provided a do-it-yourself spread on how to make a pipe-bomb…..The papers, thirsty and cunning in a news-dry holiday period, were still going strong.”

The Mad Bomber case is a textbook example of early profiling techniques of the day, and the first with a forensics psychologist (Dr. James Brussel) at its forefront.

In January 1957, a Con Edison secretary discovered similarities between letters from ‘F.P.’ published in newspapers and wording in Metesky’s old personnel files. Police were at Metesky’s doorstep in Waterbury a couple days later, where he almost readily spilled the beans about his identity.

Even after his arrest, devices he had previously planted were still being discovered, such as one at the Lexington Avenue movie theater (at 51st Street) that had been buried in a seat cushion years before.

(Photo by Peter Stackpole, Google Life images)

Metesky was declared insane and sent to upstate’s Matteawan Hospital for the Criminally Insane. Believe it or not, he was freed on December 13, 1973, and lived for twenty more years back at his home in Waterbury. He claimed to the end that he designed his bombs not to hurt people. And yet, of course, many did.

1 reply on “When The Mad Bomber Terrorized New York City”

I remember as a ten year old bronx boy who loved to ride the el/subway, and going to the movies that I was really pissed off at the mad bomber for causing me to be afraid of enjoying both activities. Thanks bowery boys, just found your site, Ii’ll be back. Jim former Pelham Bay guy.