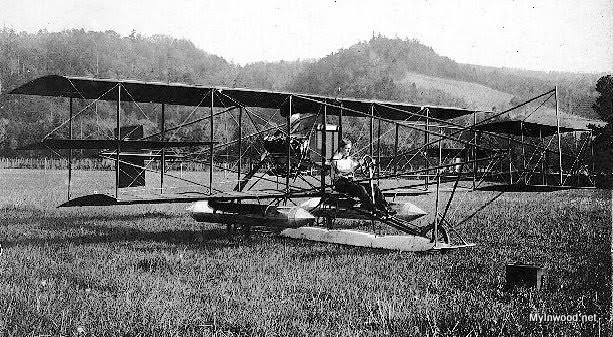

Up In The Air: Glenn Curtiss and his Hudson Flyer

Picture courtesy glenncurtiss.com

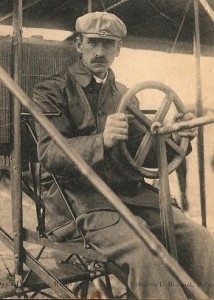

In 2010, there will be well over 100 million passengers coming and going from the New York metropolitan area’s three principal international airports. In 1910, you could count the number of passengers on your hand. And the pilot and passenger of the very first long-distance flight to New York was professional aerial derring-do Glenn Curtiss.

There had not even been an airplane over New York skies until the previous year, when Wilbur Wright flew over the length of Manhattan in honor of the Hudson-Fulton Celebration. (Hear more about it in our LaGuardia Airport podcast.) Curtiss, who had proven himself earlier that year in the world’s first air meet in France. was also commissioned to fly alongside Wright in a separate plane from Governor’s Island that October 1909, but his craft barely made it off the ground. A crushing defeat, because he and the Wright Brothers were hardly friends.

In fact, the Wrights were suing Curtiss (and his collaborator, the phone man Alexander Graham Bell) for patent infringement in a New York court in 1910; his early flying machines were similar in design to the Wrights, they claimed. The nasty court proceedings would cost both parties thousands of dollars; Wilbur would even die in 1912 before the case resolved (eventually in the Wright’s favor).

Every flight Curtiss took cost him royalties to the Wrights. Luckily for the speedster, raising money wasn’t difficult for a young daredevil, as newspaper men of this time loved offering prize money for spectacular stunts. News moguls like Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst just loved to pay people to create news.

In January, Curtiss would win a speed race in Los Angeles funded by railroad magnate Henry Huntington, who more than made up his $50,000 prize offering when 20,000 spectators took his train to the event. Pulitzer’s New York World would provide a smaller prize ($10,000), but it would have been of great appeal to Curtiss: the cash went to the first person to fly from Albany to New York, about 150 miles, essentially the first long-distance flight between cities ever made. Still smarting from Wilbur’s 1909 Hudson-Fulton victory, Curtiss wanted to make his mark over New York City.

On the morning of May 29, 1910, Curtiss and his newly named Hudson Flier took off from Van Rensselaer Island, just next to Albany, and glided above the Hudson, as a trainload of New York Central passengers (including Curtiss’s wife) followed from below. Pilots would not yet have the fuel capacity to make one continual flight; it was enough I suppose just to make it from one destination to the other in the same plane, in one piece! Curtiss stopped once for a fuel break in Poughkeepsie; an hour later, winds off of Storm King Mountain almost ripped his plane asunder.

On the morning of May 29, 1910, Curtiss and his newly named Hudson Flier took off from Van Rensselaer Island, just next to Albany, and glided above the Hudson, as a trainload of New York Central passengers (including Curtiss’s wife) followed from below. Pilots would not yet have the fuel capacity to make one continual flight; it was enough I suppose just to make it from one destination to the other in the same plane, in one piece! Curtiss stopped once for a fuel break in Poughkeepsie; an hour later, winds off of Storm King Mountain almost ripped his plane asunder.

Right as Curtiss set his sights on the young Manhattan skyline, his plane began leaking oil and the pilot had to touch down again, unceremoniously landing in New York City — but in Inwood, not the finish line at Governor’s Island. He touched down unannounced on the estate of William B. Isham, where Isham’s daughter Flora and her husband Minturn Post Collins offered the pilot gasoline and oil.

By that time, a crowd of New Yorkers had descended onto the Isham estate to witness this incredible sight. Curtiss thanked Collins and his wife, rolled his plane off the estate and into the air. He coasted along Manhattan’s west side, over the harbor and around the Statue of Liberty, finally landing at Governor’s Island just in time for lunch.

Within the month, Curtiss’ amazing flight would be bested by his friend Charles Hamilton, flying round trip in June 1910 from New York to Philadelphia and also winning a $10,000 prize in the process.

You can read more about Curtiss’ time in Inwood at here.