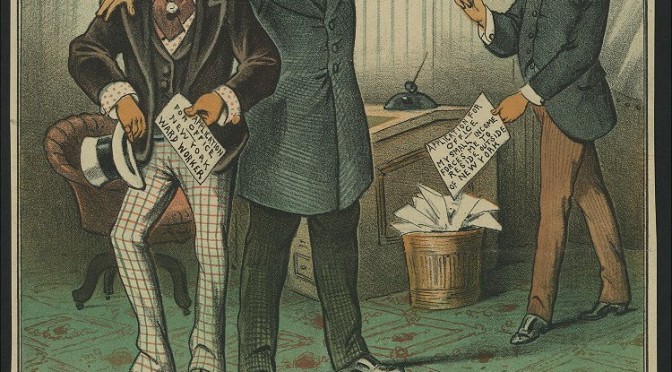

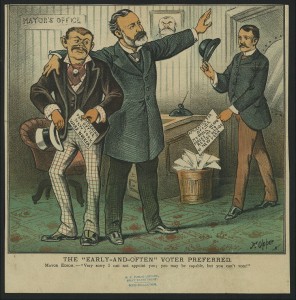

Above: a cartoon mocking Edson’s hiring practices (courtesy New York Public Library Digital Gallery)

KNOW YOUR MAYORS Our modest little series about some of the greatest, notorious, most important, even most useless, mayors of New York City. Other entrants in our mayoral survey can be found here.

In office: 1883-1884

Although the political career of one-term mayor Franklin Edson was indeed brief, he helped commission both the city’s largest acquisition of park land and one of its biggest improvements in drinking water. And he was present for the opening of one of New York’s greatest landmarks. So how did the city thank him for his service? By nearly throwing him into Ludlow Street Jail — where Boss Tweed had been left to rot just a few years before.

Edson, a transplanted New Yorker, was a farmboy from Chester, Vermont, born in 1832, who distinguished himself in the art of whiskey distillery — distinghished with “precocious tact and sagacity,” in fact.

Edson, a transplanted New Yorker, was a farmboy from Chester, Vermont, born in 1832, who distinguished himself in the art of whiskey distillery — distinghished with “precocious tact and sagacity,” in fact.

He worked his way over to Albany, New York, as a successful distiller and grain merchant with his brother. Franklin took full advantage of drink demands during the Civil War; his company soon became so profitable that he moved the entire venture to New York in 1866.

Edson, a burgeoning booze mogul of sorts, immediately became a prominent merchant voice in Manhattan, becoming the president of New York’s Produce Exchange three times, serving his first term in 1866 before he had to time to even unpack his moving boxes.

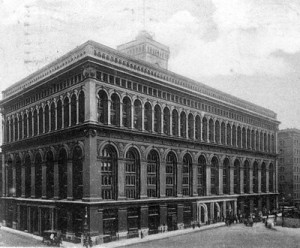

While this naturally afforded Franklin an incredible vantage for commercial power, it would soon place him in the crosshairs of political power as well. In later years he would be most proud of his Exchange days, priding himself in being one of the encouraging voices to tear down the inadequate castle-like Produce Exchange (designed by Leopold Eidlitz) and erecting the larger, more impressive George Post-designed Produce Exchange building near Bowling Green (which itself would be sadly torn down in 1957).

Below: the new Produce Exchange

What sets Edson apart from other future mayors of the time — and what might have potentially hindered his political ambitions — was that he loved the countryside, in this case Old Fordham Village, today a neighborhood in the Bronx.

He would live here for many years and would remain a member of the (now landmarked) Episcopal Saint James Church in Fordham for most of his days. Whether by design or coincidence, this love for what would become New York’s northern borough would soon prove fruitful for the city as a whole.

Franklin was also a practicing anti-Tammany Hall Democrat. And who wouldn’t be anti-Tammany during the 1870s? Edson became politically active in the years following the Boss Tweed scandals, when Tammany was still reeling for the highly publicized affair involving Tweed and then-mayor A. Oakley Hall.

Despite a slow rebounding, Tammany would never fully rinse off the stench of corruption. Naturally, Edson’s prominence among the business class married nicely with mayoral ambitions by the mid 1880s and would eventually include a denunciation of Tammany practices and condemnation of Tammany boss John Kelly (at right). But not at first.

For the election in November 1882, the various Democratic factions, including the still-potent Irving Hall, soon decided on the relatively green Edson, because he was a uncontroversial, neutral choice. To Tammany’s Kelly, Edson must have seemed a fairly agreeable pick indeed compared the previous mayor William Russell Grace, a reform Democrat rebelliously outside the realm of Tammany’s power.

Edson easily swept past his opponent, railroad man Allan Campbell — a sweet victory for John Kelly, as it was Campbell that had replaced Kelly as the city comptroller several years previous under the administration of mayor Edward Cooper. (Check out Edward’s entry for some juicy details of the Kelly/Cooper rivalry.)

How did a political nobody — a “seven day wonder in the political world” — sweep so handily into office? It helps to ride coattails; during that same election, the popular Democrat Grover Cleveland was elected the governor of New York.

At first, Edson gave in readily to political favoritism, paying back some of his Democratic cohorts — including many of the Tammany variety — with lucrative city jobs, a decision which disgruntled many of his former supporters. In fact, he even appointed Richard Croker as fire commissioner; Croker would become the head of Tammany Hall in the 1890s. (Harper’s Weekly has a coy little cartoon chiding the Croker decision.)

Like many before him, however, Edson soon grew tired of Tammany’s corrupting influence and began adopting reform policies which were currently being installed on the state level. And also like many before him, his against-the-wind attempts at reform would essentially spell the end of his political career. Edson would serve but a single term and would almost entirely vanish from politics afterwards.

But not before throwing his weight behind a major expansion of the Croton Aqueduct, which within in a few years would triple the supply of water into the city. (In fact, most of the expansion he pushed for is still in use today.)

Edson is also partially responsible for the huge increase in New York park land, commissioning a citizens group in 1884 to lobby the state to purchase lands in the area of today’s Bronx; accordiing to an old Bronx history, “the ‘new’ parks, as they were called, comprised 3,757 acres, now included in Van Corlandt, Bronx, Pelham Bay, Crotona, St. Mary’s and Claremont parks.”

And most notably, he was the first New York mayor to walk the Brooklyn Bridge, astride president Chester A. Arthur and governor Cleveland on the bridge’s opening day, May 24, 1883. He would be met in the middle by the mayor of Brooklyn — future New York mayor — Seth Low.

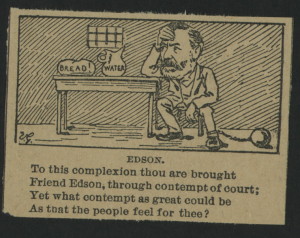

He might have crept quietly into obscurity had Edson not been accused of contempt of court shortly after he left office, threatening a man in his early 50s with jail time with a stint at the notorious Ludlow Street Jail. Apparently, despite a court injunction, Edson had quietly made promotions to two posts — the Commissioner of Public Works and the Corporation Council — on his last day in office. However, after a stressful two months in court, Edson was declared not guilty of the crime.

This did not stop people from imagining the ex-Mayor trapped behind bars, as the newspaper illustration below evidences:

Edson died in 1904, at his home on the Upper East Side. 42 West 71st Street, to be exact, a block from the Dakota Apartments, which were completed during his tenure as mayor.

2 replies on “Mayor Franklin Edson: Bronx man and distillery king”

I know this is 11 years late, but you missed one of the most notorious things about Franklin Edson. In 1903, his son, Henry Townsend Edson, shot to death his wife’s best friend (right in front of her) after she spurned his demand that she run off with him. He then turned the gun on himself. It also turned out that he’d embezzled $59,000 from his church, where he was the treasurer. See the New York Times for Sept. 3, 1903.

That’s amazing! Thank you.