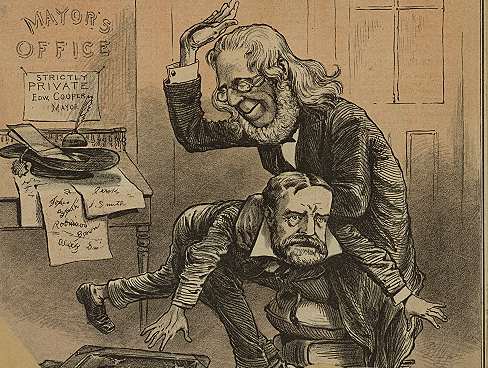

ABOVE: Puck Magazine satirizes father and son, Peter and Edward Cooper

KNOW YOUR MAYORS Our modest little series about some of the greatest, notorious, most important, even most useless, mayors of New York City. Other entrants in our mayoral survey can be found here.

In office: 1879-1880

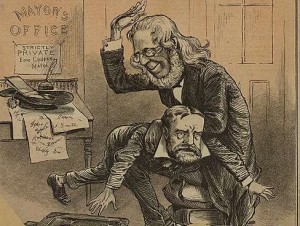

Many of us must inevitably live in the shadows of the achievements of our parents. Edward Cooper, while no slouch, suffers from the competing bios of two great men in his family — papa Peter Cooper, New York’s cleverest industrialist, and brother-in-law Abram Hewitt, a transformative city leader.

Many of us must inevitably live in the shadows of the achievements of our parents. Edward Cooper, while no slouch, suffers from the competing bios of two great men in his family — papa Peter Cooper, New York’s cleverest industrialist, and brother-in-law Abram Hewitt, a transformative city leader.

Like Hewitt, Cooper too was mayor of New York, from 1879-1880. Cooper’s tenure wasn’t exactly memorable, but the years following up to it certainly were.

Edward was born on the outskirts of town (i.e., 28th Street and today’s Park Avenue South) in October 1824, the only surviving son of Peter and his wife Sarah, a child with the unique advantage of having one of America’s leading inventors to apprentice from. Peter was already wealthy from his Kips Bay glue factory and employed his free time tinkering, experimenting and dreaming. In fact, Edward was celebrating his third birthday when Peter brought into this world another of his pride and joys — the Tom Thumb, the first operable, steam-powered train engine.

Not surprising, Edward quickly followed his father’s intellectual lead. During his early days in public school, “it was often said of him that there was never a time in his life when he would not sit up half the night to solve a difficult problem in mathematics or engineering which were his especial delights.” Like father, like geek!

Edward went to Columbia University where he befriended his fellow student Abram Hewitt, and the two set out for an educational European vacation in 1844. On the way back however, they were both nearly killed in a shipwreck, stranded with the crew for many days without food or water,

Leave it to outrageous hearsay, but allegedly during this shipwreck, according to Edward’s own obituary, he was almost cannibalized for food by the survivors.

“One report had it that the castaways were so hungry that lots were cast to see who should be eaten. Mr. Cooper drew the unlucky number, but Mr. Hewitt asked to take his place.

“I have brothers,” Mr. Hewitt said, but you are your father’s only son and his life is wrapped up in you. Let me take your place.” Now that’s friendship!

This devastating experience drew the Coopers and the Hewitts together. In fact, Hewitt would later marry Edward’s only sister Sarah Amelia. Edward and Abram, meanwhile would go into the ironworks business together, with capital from Peter Cooper. The results would make them very rich men with foundries in Trenton, New Jersey, producing “mortar beds and gun carriages” in the years leading up to the Civil War.

In 1865, Peter gave control of his coveted glue factory to Edward and soon young Cooper became as distinguished a New York business man in his own right. Just in time to pursue a political career.

Edward was a Democrat, but not of the tainted Tammany Hall stripe. Cooper came from the short-lived rival and reform-minded Irving Hall, battling to sweep away city hall corruption as practiced by the machinations of the other, far powerful Democratic machine. In fact, he would prove instrumental — both through his close friend Samuel Tilden, and as a member of the reform Committee of 70 — in helping bring down the ring of Boss Tweed and the corrupt mayoralty of A. Oakley Hall. He later ardently supported his friend Tilden during his contentious run for the White House in 1876.

The rift was caused by two rival party bosses — John Morrissey, a prize-fighter turned state senator who drew men like Cooper by recoiling from the excesses of Tweed-style politics, and ‘Honest’ John Kelly, who at first rallied in reform rhetoric with Tilden and others but later rebuffed his former allies when he became New York comptroller.

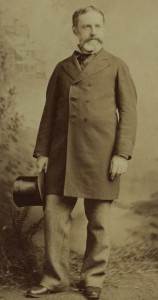

Morrissey ran for state legislature defeating Tammany stalwart August Schell. August turned around and ran for mayor, but this time it was Edward Cooper who defeated him in the fall of 1878. (Ironically, Cooper had to cull together a coalition of Republicans and anti-Tammanys in order to claim victory.)

Below: the electoral decision between Schell and Cooper, as seen through the satire a political cartoon.

The conflict above between Morrissey and Kelly deserves some greater inspection in this column at a later date. Only know that it was John Kelly’s ascension into the comptroller seat before Cooper became mayor that basically ensured Cooper would not be any kind of an effective mayor at all.

Most of Cooper’s time was spent in political infighting, and his prime objective — to reform the corrupt police department — was continually met with criticism, mostly led by Kelly.

Let’s just say, Kelly and Cooper really didn’t get along. Or, in Kelly’s own words, “Let, Edward Cooper, that infamous hypocrite who occupies the Mayoralty chair know that, after his betrayal of the Democracy, he is no nearer Heaven, nor Samuel Tilden near the White House, than they were before!”

Interestingly, Cooper is front and center of a small but precious moment in New York history: the debut of Cleopatra’s Needle, the 3,500 year old obelisk from Egypt planted in Central Park on Oct 9, 1880.

Near the end of his life, Edward would take another, more familiar and far less strenuous office — the president of Cooper Union — in 1898. He died seven years later, in 1905.