Today is the 105th anniversary of the Kingsland factory explosion. To mark the occasion I’m reposting this article originally released on the 100th anniversary of this mysterious disaster.

On the afternoon on January 11, 1917, workers in downtown Manhattan skyscrapers were jolted from their desks by a startling sight in New Jersey — an exploding munitions plant in Kingsland, a small community about nine miles south of New York City.

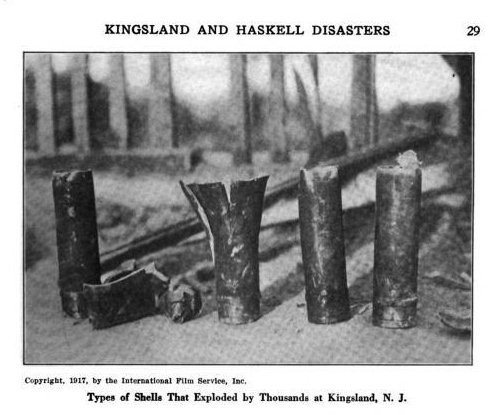

“For four hours Northern New Jersey, New York City, Westchester and the western end of Long Island listened to a bombardment that approximated the squad of a great battle — a bombardment in which probably half a million three-inch high explosive shells were discharged.” (New York Times)

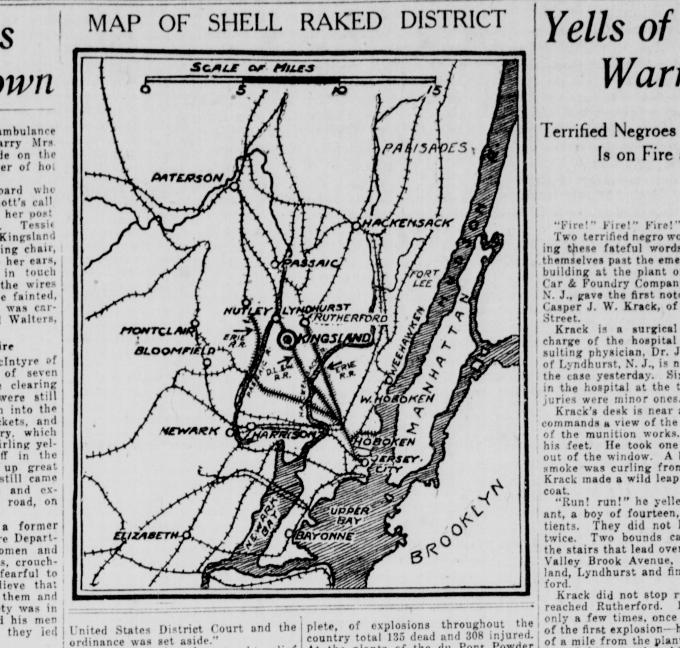

A map from the New York Tribune:

A Canadian company Canadian Car and Foundry had been producing weaponry for Russia and Great Britain in Kingsland. All of it went up in a dramatic and deathly burst. Two square miles of town completely flattened.

Given the dangerous work of manufacturing exploding devices, unfortunate accidents occurred all the time. But was this something more? Was this an act of sabotage?

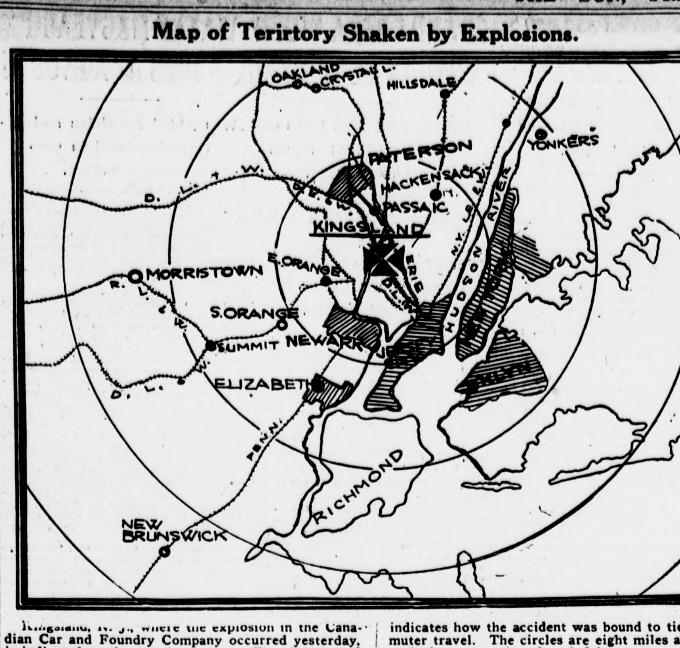

A slightly less interesting map from the New York Sun:

The region had been on edge for a few years. Although the United States had still not yet entered the European conflict, fireworks and munitions plants had been producing weapons for Allied forces — France, the United Kingdom and Russia.

By 1917, America was clearly considered an enemy agent by the warring Germans.

Just a few months earlier, on July 30, 1916, the area shook with the horrific explosion at Black Tom Island in Jersey City, NJ, an act of sabotage that blew out thousands of windows and even damaged the Statue of Liberty. (We recount the entire story in our podcast from 2016 about the Black Tom Explosion.)

Seven people died in that explosion the previous year. But in Kingsland that day, with a deadly blast even greater than that which had occurred at Black Tom, nobody died.

This is attributed to the heroism that day of a single woman — Lyndhurst resident Theresa Louise “Tessie” McNamara.

Tessie was a switchboard operator at the plant that fateful day. The explosions began in a building used for cleaning artillery shells. Once they began, the company’s buildings were a scene of confusion and chaos.

McNamara was immediately informed of the blaze, but kept to her station, broadcasting messages to every building in the complex, even as most others fled the site fearing for their lives.

From the New York Tribune: “McNamara, operator of the Kingsland Central, stayed in her revolving chair, with the receivers clamped to her ears, keeping the terrified town in touch with the outer world until the wires were blasted away. Then she fainted, with her job well done, and was carried away to safety by Fred Walters, of East Rutherford.”

From the New York Sun: “It was emphasized from a dozen sources that one girl’s bravery stood between many hundreds of men and shocking death.”

From an interview of Miss McNamara: “Shells were dropping all around and I thought every minute would be my last. About a dozen buildings were now on fire and I had completed 36 calls. No more were coming in and I started for the door without coat or hat. Just then three of the boys who had missed me appeared in the office doorway. One of them shouted, “Come on now, Tess!” but I couldn’t walk. My courage left me and I needed their assistance to get out” [source]

The explosion stranded tens of thousands of passengers along train lines in New Jersey. The explosion’s curious timing — at the end of the day, near closing time — meant that trains were filled with commuters on their way home from work. Nobody was injured, but nobody got home in time for dinner that evening.

This begs the question — was the Kingsland Explosion purposefully set? Nobody was ever arrested, although many reported the mysterious behavior of an employee named Fiodore Wozniak who lived in New York.

From a statement by Wozniak’s foreman: “I noticed that this man Wozniak has quite a large collection of rags and that the blaze started in these rags. I also noticed the he had spilled his pan of alcohol all over the table, just preceding that time. I also noticed that someone threw a pail of liquid on the rags or the table almost immediately in the confusion ….. Whatever the liquid was, it caused the fire to spread very rapidly and the flames dropped down on the floor and in a few minutes, the entire place was in a blaze.

It was my firm conviction from what I saw, and I stated, that the place was set on fire purposely, and that has always been and is my firm belief.“

Wozniak later disappeared and never questioned.

In the 1970s, Germany did pay tens of millions of dollars in reparation for various acts of sabotage within the United States, but did specifically accept the blame for the Kingsland disaster.

Today you can visit a unique site associated with the explosion — a smokestack that somehow survived the disaster, near a plaque dedicated in Miss McNamara’s honor. [More details here]

For additional information visit the Lyndhurst Historical Society page on the disaster.

2 replies on “The Kingsland Factory Explosion (and the switchboard operator who saved the day)”

The saga of the Kingsland Explosion is the stuff of a disaster/action/espionage thriller. How this story was not made into a movie in time for its centennial is beyond me. It has so many elements that make it timeless, not least of which is the extraordinary heroism of a humble young woman whose selfless courage almost certainly saved the lives of hundreds of innocents. Added to that are terrorist acts perpetrated by enemy agents, the quick-thinking actions of the sanitarium staff on Snake Hill (calming their terrified patients by throwing an impromptu ice cream and candy “celebration”), and the thousand and one individual human interest stories that emerged in the aftermath of this epic catastrophe. Tessie McNamara was a true American hero(oine) and her bravery deserves to be immortalized on the silver screen!

I grew up in Lyndhurst, New Jersey. I was born in 1947 in Newark, N.J. and my family moved to Lyndhurst (I believe) in 1951. I am amazed and just a little disgusted that this incident was never taught to me in school. I went to Roosevelt School through the 8th grade, and 1 year of high school at Lyndhurst High. My family then moved to California.