In the early and mid-nineteenth century, the Underground Railroad secretly escorted tens of thousands of Southern enslaved people to Northern destinations, where slavery was illegal. The African American publisher David Ruggles was born a freeman in Connecticut and moved to New York to energize the emerging abolitionist move- meant via the New York Vigilance Committee, one of the city’s most influential abolitionist collectives.

And thank goodness David Ruggles was there.

Below: One of the few extant depictions of David Ruggles

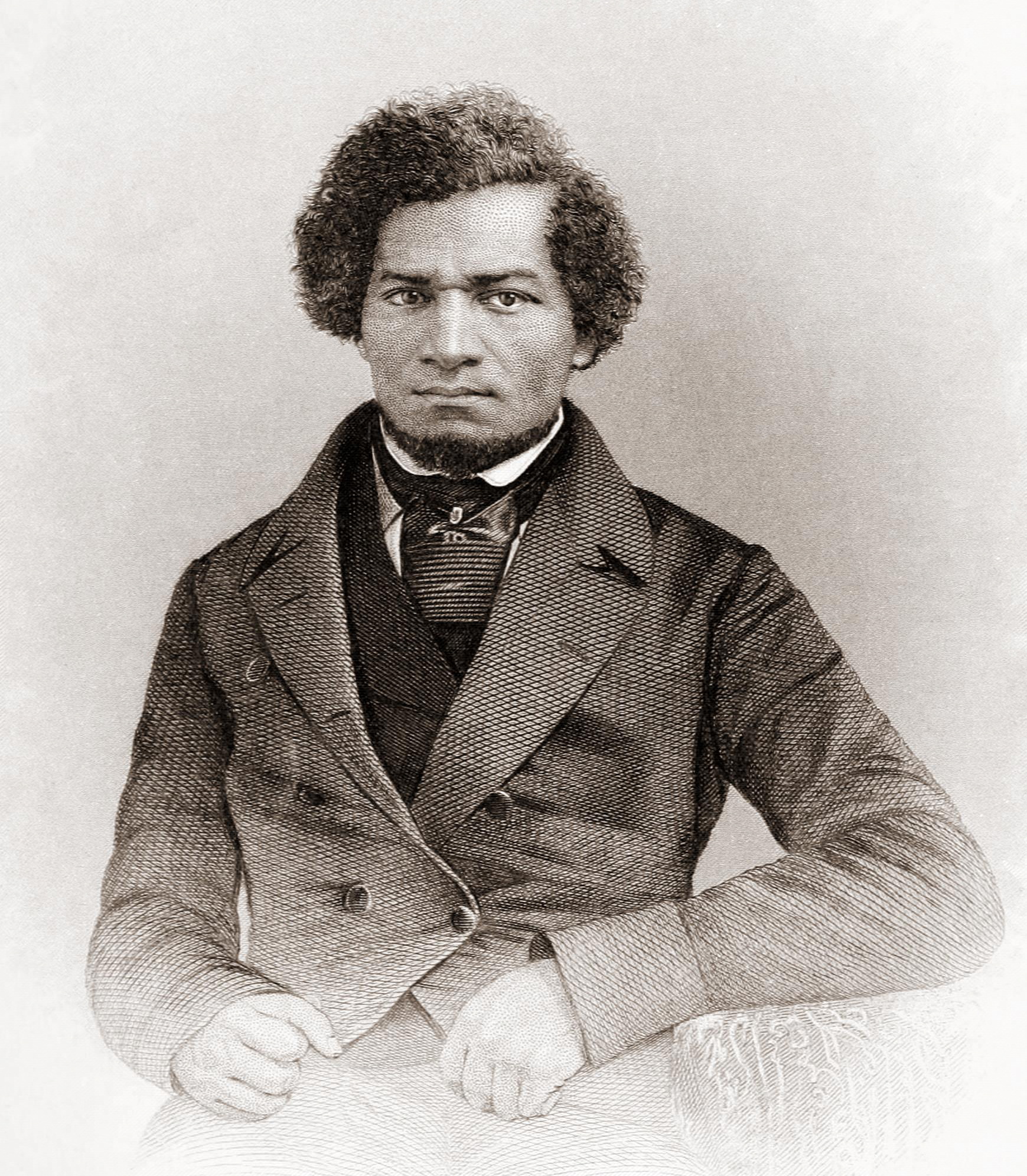

At his home at 36 Lispenard Street (in today’s Tribeca neighborhood), Ruggles ran a printing press and reading room for abolitionist literature. He also sheltered an estimated 600 fugitive slaves here over the years, including in 1838 a man named Frederick Washington Bailey, who had escaped a life of slavery in Maryland.

Under a new name, the abolitionist Frederick Douglass later wrote about how he felt arriving in New York. The following words are from the Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: From 1817-1882:

“My free life began on the third of September, 1838. On the morning of the fourth of that month, after an anxious and most perilous but safe journey, I found myself in the big city of New York, a free man – one more added to the mighty throng which, like the confused waves of the troubled sea, surged to and fro between the lofty walls of Broadway.

Though dazzled with the wonders which met me on every hand, my thoughts could not be withdrawn from my strange situation.

I have often been asked how I felt, when first I found myself on free soil; and my readers may share the same curiosity. There is scarcely anything in my experience about which I could not give a more satisfactory answer. A new world had opened upon me.

If life is more than breath, and the ‘quick round of blood,’ I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life.

In a letter written to a friend soon after reading New York, I said: “I felt as one might feel, upon escape from hungry lions.”

Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted; but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill of pen or pencil.

While the building which sheltered Douglass on Lispenard Street is no longer there, a plaque is affixed to the current structure at that spot, marking Ruggles — and New York’s — contribution to the liberation of Southern slaves.

In tomorrow’s new Bowery Boys podcast, we’ll look at the story of Mr. Ruggles more closely and explore the many paths taken through New York City along the Underground Railroad.

This is an excerpt from the Bowery Boys Adventures In Old New York, now available in bookstores everywhere.