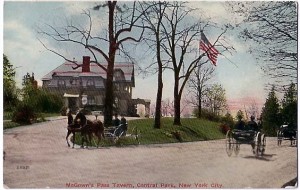

McGown’s Pass Tavern (date unknown, but possibly around 1913

We’re finally moving on from Central Park, but not before observing perhaps its most historically significant area — McGown’s Pass and the Block House.

Located on the northern portion of the park, next to the charming Harlem Meer, are a collection of hills and bluffs left over from its original topography. Not surprisingly, these higher altitudes played a pivotal role during the American Revolution.

A narrow passage between the hills was named McGown’s Pass after Andrew McGown, owner of a popular tavern that sat alongside here. Kept in the McGown family, the tavern was torn down early in the century but rebuilt in the 1880s. In 1895, McGown’s was strangely granted its own election district as, being inside the park, it lay outside normal district boundaries. “There were four voters in this territory last year,” declared the New York Times. “They are four men employed at McGown’s Pass Tavern.” The tavern was eventually torn down in 1917.

It was through McGown’s Pass that George Washington traveled on September 15, 1776. He and a portion of the Continental Army had escaped up to today’s Washington Heights area; when hearing that part of his army had been stopped by the British, Washington rode down the pass and led the remaining troops back up to their fortification in the Heights. He rode back through the pass again seven years later, this time as the victor.

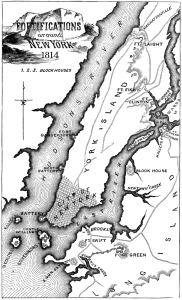

The British and their Hessian mercenaries built forts here to cut Manhattan off from the mainland. Later New Yorkers would seize upon this idea during the early days of the War of 1812. Not willing to become property of the British once again, Manhattan mobilized for any potential battles, building forts all over the island and throughout the harbor. It was here at McGown’s pass that the erected a few fortifications, including Fort Clinton (not to be confused with the fort in Battery Park, although both were named for DeWitt Clinton) and Fort Fish, named after Major Nicholas Fish, father of the New York senator Hamilton Fish.

Nothing much remains of these two old forts, which were never used as the War of 1812 never made its way to the city. There are, however, two remaining structures from the early days. A stone ledge overlooking the meer is all that remains of Nutter’s Battery, named after a farmer who owned the property. And nearby stands the Block House, its stone face still fairly solid, once armed with cannons and used to hold ammunition — that was, of course, never needed. The Block House was fairly intact when Olmstead and Vaux included it in their plans for the park, using the building as a ‘picturesque ruin’ covered in vines.

Here’s an illustration of how the Block House looked in 1860:

For a short while, this military site was even used as a convent and hospital. In 1847 the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul opened a ‘motherhouse’ and school called the Academy of St. Vincent. The nuns left when the area was incorportated into the park, however the building stood until the 1870s, when it burned down and was replaced with the refurbished new McGown’s Pass Tavern mentioned above. (This site has some great pictures of where the convent once stood.)

This is a bit tangental, but I love this story. A plaque was erected at the old site of Fort Clinton in 1906 and unveiled in a publicized community event for children. It was apparently difficult for some people to find the location and “several chivalrous lads” guided people through the park to the unveiling.

However, the Times reports an incident that might be the only real battle that ever occured at this storied historical spot:

“Among the boys interested in the tablet unveiling were several whose spirit of mischief overcame their sense of the proprieties. These made misleading arrow signs …. and caused a number of persons to go far afield and arrive at the exercises late and angry. These mischievous youngsters were caught at their annoying trick by boys who were more sober and serious. Then there was a short scrimmage, and the mischievous lads scurried away through the Park.”

Finally, from a 19th century book on the War of 1812 comes this spectacular map of the various fortifications built in anticipation of battle. Its dimensions are greatly distorted of course, but it lists the forts and blockhouses that stood in this area as well as those such as Fort Gansevoort and Fort Greene (click on the image to look at it more closely):

5 replies on “McGown’s Pass: the original tavern on the green”

Before McGown’s Tavern existed, there stood a hotel named Stetson’s which eventually changed it’s name to Mt. Saint Vincent Hotel. The proprietor of the establishments was Columbus Ryan the first superintendent of Central Park. The building burned down 1/2/1881.

Helpful note. Thank you. The original McGown’s Tavern was first built c1750 by John Dyckman. Stetson’s referred to in note above, was built after the Civil War.

The original tavern was the Black Horse, which Daniel McGowan bought along with 10 acres of property from his wife’s brother-in-law Jacob Dyckman in March 1756. The McGowans leased the inn to John Leggett and family in the 1780s, held the property till the 1840s. The Mount St. Vincent’s Hotel ran in the old McGowan house and convent property from 1866 till early 1881, when most of it burned down. The refreshment house was rebuilt in Central Park ‘carpenter gothic’ style and continued till 1915. After 1890 it was renamed the McGowns Pass Tavern. Note that these latter roadhouses were built over the foundations of the Dyckman/McGowan houses and Mount St. Vincent convent, rather than on the site of the original Black Horse Tavern, which is on the other side of East Drive (Post Road). There is still a pile of rocky rubble in the Bridle Path at the tavern’s approximate location.

[…] Bowery Boys History said, “Located on the northern portion of the park, next to the charming Harlem Meer, are a collection of hills and bluffs left over from its original topography. Not surprisingly, these higher altitudes played a pivotal role during the American Revolution. […]

Love this! I’m directly related to the first John McGown from Scotland. There was an Andrew McGown in our ancestors also. Could I be related to the NY Andrew?