Some architectural monstrosities just beg to be ripped upon. Topping this list is One Union Square South, a bland 33-story structure and pioneer in the mall-ification of Union Square. Although its storefronts feature a Circuit City and a dying Virgin Mega-store, One Union Square South is defined by a piece of public art that has only gotten more atrocious and weird over time.

The Metronome was a project three years and $3 million in the making when it was finally installed in February 1999. It has confused and horrified New Yorkers ever since. The 100-foot Kristin Jones and Andrew Ginzel display features a brick wall striated with the undulations of water waves, interrupted with such objects as a boulder, a long tube frozen in the swing of a ‘metronome’, and a sphere which registers the moon cycles. Smoke occasionally burps through the hole in the middle, and a gigantic hand — modeled after the hand of George Washington across the street on his equestrian statue — beckons the viewer to stop and gawk at it.

Nearby is a row of 80s-era calculator digits, rolling at different speeds. The six numbers on the left indicate the proper time (i.e. 9:34 am and 21 seconds = 093421).

The six numbers on the right display the amount of time before midnight, except to be quirky, they put it backwards. So, using the prior example, there are 14 hours, 25 minutes and 39 seconds to midnight. In Metronome world, you write that as 392514.

The three digits in the middle are too blurry, presumably in the rush of micro-seconds. (Except, of course, when you take a picture of it.)

Since this piece begs the viewer to speculate the passage of time, perhaps its time to speculate what sat here at One Union Square South before this dated piece was even here. (To be fair, the piece seemed dated the moment it was installed in 1999.)

One Union Square South replaced the less glamorous address 58 East 14th Street. Passersby in the early 90s saw it as a frumpy building with modest retail space dominated by a gigantic McDonalds sign. What many may not have known was that this building contained the oldest theatrical space in Manhattan.

Rumors of this secret stage had persisted since the 1970s, but it wasn’t until some clever detective work by a New York Times reporter verified in fact interior walls were built during its transition into retail space, severing the stage from a vast auditorium, sitting empty for decades.

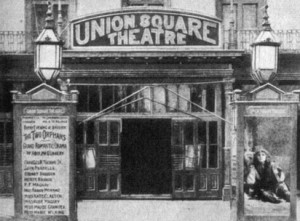

It had once been the Union Square Theater. In its final days of operations, from 1896 until the late 30s, it had been a cinema for silent features and ‘racy’ pre-code pictures. As with many stages, it converted to showing films after a brief stint from 1893 to 1896 as a vaudevillian showcase. The stage saw the debut of a young entertainer named George M. Cohen, who was originally supposed to perform with his family The Four Cohens. But owner B. F. Keith needed to fill up his bill, so young Georgie took the stage himself and the boy was greeted with apparent indifference. (You can see a variant of this event in the film ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy’.)

Before the racy films, before Cohen and the vaudeville, the Union Square Theater was a legitimate stage, showing mostly unsuccessful fare such as the un-intriguingly named ‘A Woman’s Strategem’. That show was apparently significant enough to merit articles about the details of the leading lady’s costumes — “a very quaintly-designed morning gown of crepe,” “a very handsome broche with bodices of the Directoire period and point de gaze’ lace sleeves.”

The early days of the Union Square Theater sound a lot more engaging. When it opened in 1871, it was advertised as a ‘modern temple of amusement’, showcasing everything from burlesque to ballet. Its brief foray into legitimate theater — the kind that could feature costumes of ‘quaintly-designed’ crepe — came only after a small fire gutted the balcony in 1888.

Peeling time back further, we find that the Union Square Theater was carved out of the remnants of vast dining room of an old hotel the Morgan House, which was itself the five-story modification of the original building on this spot — the Union Place Hotel, built in 1850.

A descriptive 1861 travel guide refers to the Union Place Hotel as an ‘elegant establishment’, and truly this was Union Square’s high-class heyday, of upper-crust homes surrounding an earlier version of the square inspired by lush English gardens.

A cheeky 1852 guide to the city called Glimpses of New York — written by “a South Carolinian (who had nothing else to do)” — describes it as ‘kept in equal style to the New York [Hotel, one of the superior hotels of the time] and the charges are a grade higher.’

Among many famous guests of the hotel were Mary Todd Lincoln in the years after the death of her husband.

Union Square eventually became the heart of New York’s theater district, and apparently the Union Square Hotel was a bit of a hangout for the out-of-work. Dwight’s Journal of Music proclaims “…at the Union Square Hotel, there is always a host of unemployed managers and actors.”

Luxury hotels and out-of-work actors — some things about New York haven’t changed a bit.

2 replies on “The REAL story behind those confusing numbers”

I’m looking at my Currier&Ives calendar for July 2022. It shows the Union Place Hotel in a glamorous setting with wonderful horse drawn carriages and people walking in the park with a beautiful water fountain within. The hotel is glamorous. I guess the South Carolinian did know what he was talking about.

I’m at a summer home on the Connecticut shore and the Travelers calendar shows the hotel… or had the same thoughts