We really shouldn’t demonize Robert Moses as we do — he did give the city so many marvelous things — but you hear about one of his schemes that almost came to fruition and you just want to cry.

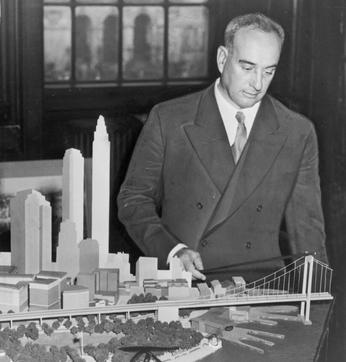

This time around, I’m referring to the Brooklyn-Battery Bridge, a potential catastrophic project Moses cooked up in the late 30s. As seen in the photograph above, of Moses standing over a model of the future bridge like that creature from Cloverfield, the bridge would have cut right along the heart of the financial district, obliterating Battery Park and much of Governor’s Island, and hoisting a crossing that would have stretched across New York Harbor to Red Hook.

How close were we to having this monstrosity? Moses wielded quite a bit of influence at this time. Having constructed the Triborough Bridge with money to spare ($30 million, in fact), Moses had the political power and wherewithal to get what he wanted even over the objections of both the mayor Fiorello Laguardia and the governor Herbert Lehman.

Laguardia has only envisioned a tunnel that would pass to Red Hook, under the harbor. But because the city was in desperate financial straits, plans for the tunnel were turned over to Moses, and voila, the underground, out-of-sight tunnel was turned into a dynamic, downtown-demolishing bridge.

Moses liked gigantic monuments, American statements as he would have referred to them. A six-lane bridge would have made money for the city via tolls and would have courted more traffic potential than a mere tunnel.

The Brooklyn-Battery would be designed by bridge master Othmar Ammann, designer of nearly half the bridges of New York City, with an anchorage plopped in the middle of Governor’s Island. The picture below, from the NY Roads website, displays a miniature of Ammann’s visionary bridge.

However, a thorn in his side Moses would grow quite accustomed to — community activism — prevented the bridge from happening.

By repositioning the purpose of an entire neighborhood — Wall Street would be feet from an off-ramp — the project was met with ire by downtown property owners. And by endangering Battery Park and its most treasured landmark, Castle Clinton, community leaders, in particular New Yorkers like Eleanor Roosevelt, got into the act.

Her participation is crucial, because it was her husband who essentially killed the project. On July 17, 1939, Roosevelt’s secretary of war Harry Woodring claimed the bridge would be susceptible to attack in event of a coming war (and war was definitely coming) and its expanse would hinder to and fro access to the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

So Moses had to settle for a ‘mere’ tunnel, and construction was started on October 1940, and then almost immediately halted do to war shortages. Ninety million dollars later, on May 25, 1950, the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, still the longest underwater vehicular tunnel in the world, was opened.