Jimmy Walker, the man who would become the mayor of New York during one of its most prosperous periods, was famously cavalier about politics. [Listen to our podcast on Mr. Walker for more information.] But in the years before he became mayor, he actually spearheaded two laws that would change New York City and the state of New York forever.

The first brought one of America’s great pastimes back into vogue: boxing. The sport was technically illegal for much of the 19th century — which didn’t stop New York from becoming the boxing capital of the United States — until a 1911 law briefly brought back.

Reformers banned it again in 1917 only to be met head-on by a powerful and well-connected member of the New York state senate who also just happened to be a boxing enthusiast — Jimmy Walker. The 1920’s Walker Law would bring back the sport for good.

His second great legislative contribution would set the stage for civil rights laws across the country.

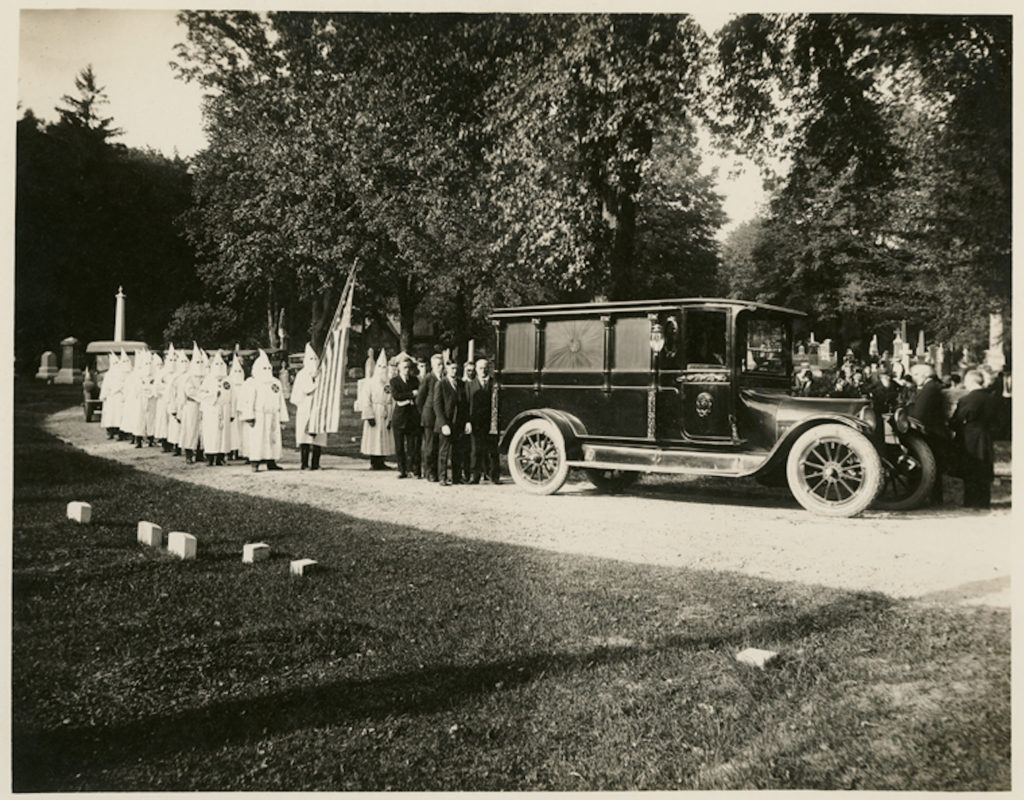

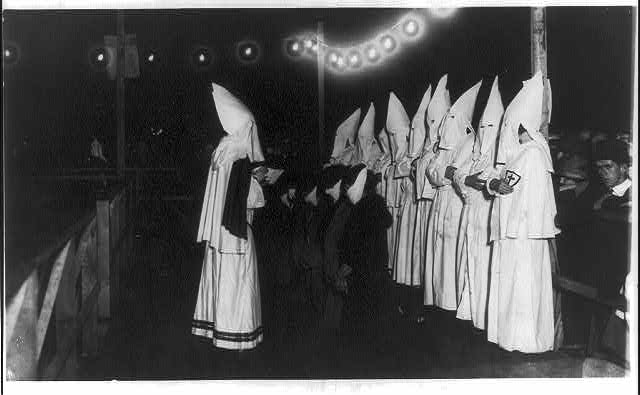

Below: Funeral procession for a Ku Klux Klan member, held in Cold Spring, Putnam County, New York, 1920s.

The Ku Klux Klan, a racist vigilante organization formed in the Reconstruction South, gained new prominence in the mid-1910s thanks to the popularity of the film The Birth of a Nation.

Feeding off anti-black, anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant fervor, the newly reinvigorated organization rose to power in the early 1920s in many big American cities. By 1922 there were 21 distinct klaverns in New York City alone.

But in a city full of powerful Catholics, immigrant groups of all types, and an empowered African-American population rising in Harlem, one might have expected a reactionary force like the KKK to be even bigger in New York City. That’s where Walker comes in.

Walker, born an Irish Catholic, was closely associated with Al Smith, the new governor of New York who was also Catholic. Both were Democrats and also aligned with the needs of the city’s Irish community. (Not to mention Tammany Hall, the political organization whose power had diminished since its Gilded Age glory days.)

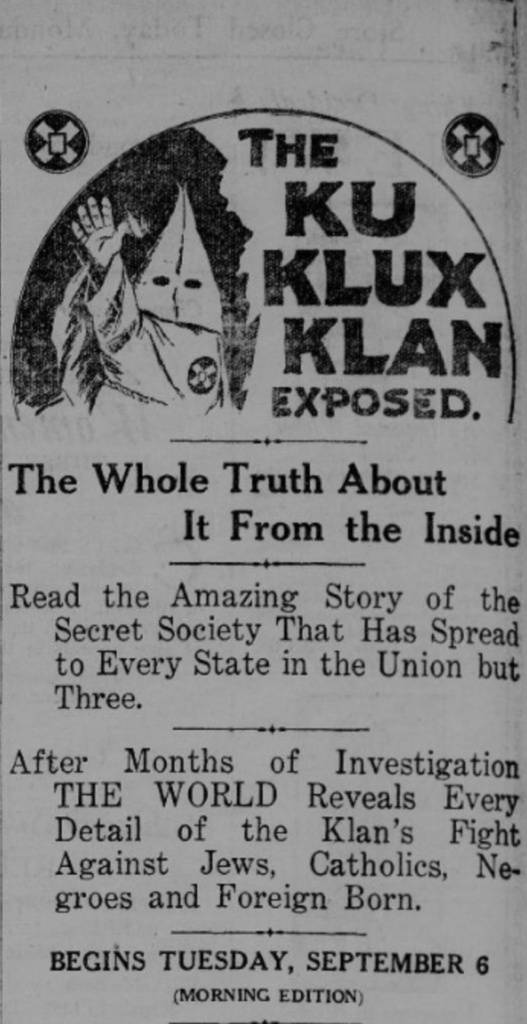

A rising swell of anti-KKK sentiment in New York City came in 1921 with the publication of a series of damning articles in the New York World, effectively neutralizing the klan’s influence in denser portions of the city. Mayor John Hylan “launched an all-out war” on the KKK, throwing them out of Manhattan wherever possible.

Below: Advertisements for the newspaper series ran in competing newspapers. From the September 5, 1921, New York Tribune:

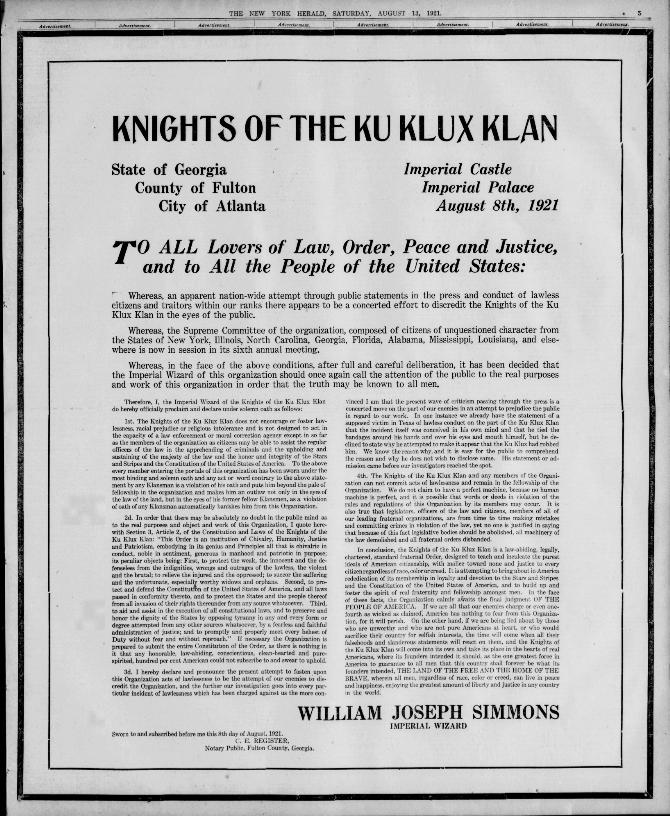

The Klan hit back with full page ads like the one below:

In no uncertain terms, Hylan declared, “Do not leave a stone unturned to ferret out these despicable, disloyal persons who are attempting to organize a society the aims and purposes of which are of such a character that were they to prevail, the foundation of our country would be destroyed.”

Below: A 1928 anti-Catholic cartoon published in the book Heroes of the Fiery Cross by the Pillar of Fire Church in Zarephath, New Jersey

But targeting the KKK was not merely a moral mission for Walker, the future mayor of New York City.

Nationally the KKK were a rising political power within the Democratic party of the 1920s. In fact the the 1924 Democratic National Convention, held at Madison Square Garden to select a presidential candidate, was almost derailed by their inclusion.

Smith, Walker’s ally, was planning on running for president in 1924. (He was overlooked that year but eventually became the party’s candidate in 1928). Limiting a hate group like the Ku Klux Klan — a hate group with rising power — within the state would certainly lessen their impact within the party.

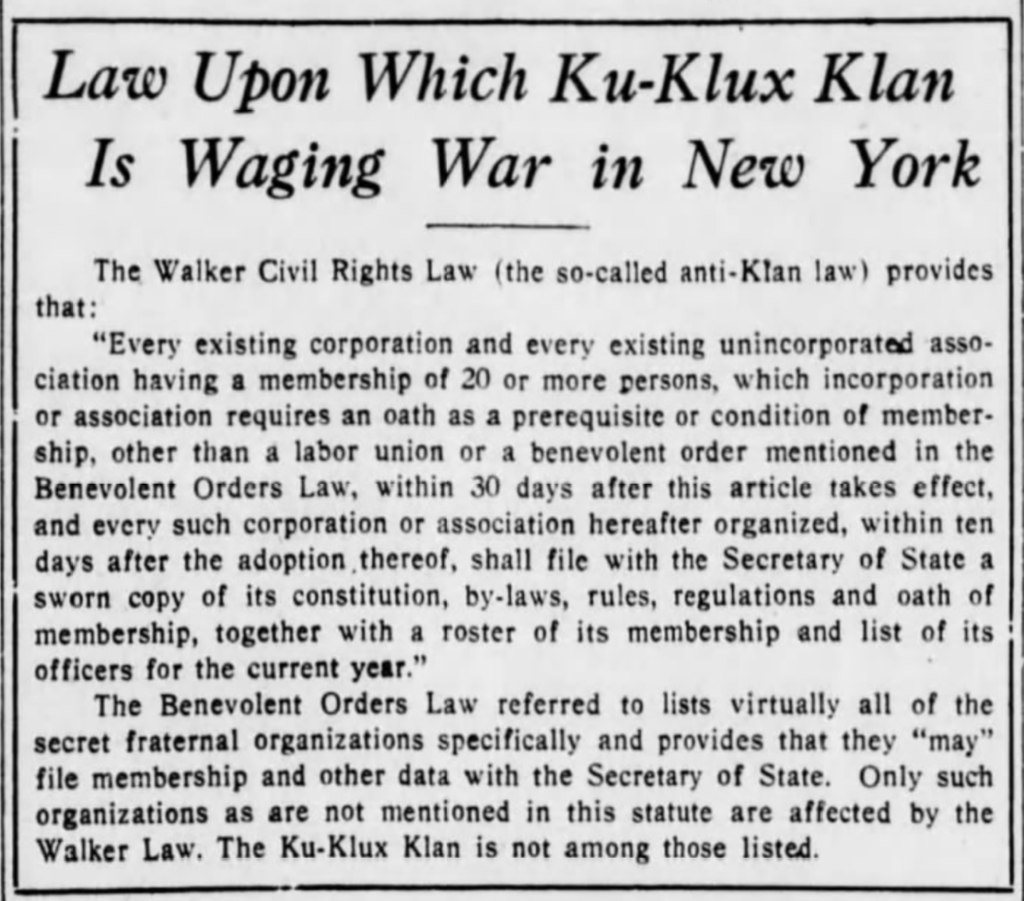

By early 1923, Walker was the state senate leader and introduced a bill into the chamber, placing limits on ‘oath-based associations’ that would require them to file a list of their membership with the state. The Klan were essentially being unmasked; the names of their members would become public record.

From the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

*The bill exempted labor unions and, “officially chartered benevolent orders” like the Elks Lodge.

The bill swept through the state senate, (barely) made it through the assembly, before landing on Governor Smith’s desk for a swift passage.

Even with the ‘anti-masking’ law in place, the klan found receptive crowds in the region.

Thousands of Klan members marched in protests immediately following the law’s implementation.

“The demonstrations by tens of thousands of Ku Kux Klansmen on Long Island, in New Jersey and in various parts of New York State yesterday and Saturday were staged as a spectacular defiance of the Klan’s enemies.” [Eagle, 5/28/1923]

- Below: A scene from Long Island, 1925. “Four women kneeling in front of strouded Klansman reading from a book; other Klansmen stand behind them on the platform; spectators watch initiation.”

The spirit of the law was more powerful than its specifics. The Ku Klux Klan was effectively turned into an illegal organization that day. Many states would use Walker’s tactics in crafting their own anti-Klan laws.

The Klan attempted to overturn Walker’s law, taking it all the way to the Supreme Court. On November 20, 1928, the court upheld the law, specifically marking the klan as a terrorist group, “its members disguised by hoods and gowns and doing things calculated to strike terror into the minds of the people.

Once the Great Depression arrived, the organized KKK was all but gone in the New York region, retreating to “a shadowy existence in the South.”

Listen to more on the story of Jimmy Walker here: