HISTORY BEHIND THE SCENE What’s the real story behind that historical scene from your favorite TV show or feature film? A semi-regular feature on the Bowery Boys blog, we will be reviving this series as we follow along with TNT’s limited series The Alienist. Look for other articles here about other historically themed television shows (Mad Men, The Knick, The Deuce, Boardwalk Empire and Copper). And follow along with the Bowery Boys on Twitter at @boweryboys for more historical context of your favorite shows.

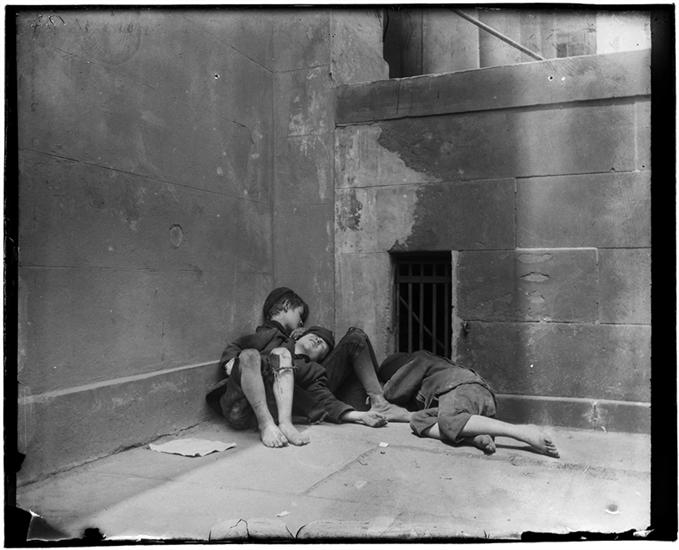

Look near the very end of the fourth episode of The Alienist, and you’ll see a surprising homage to an iconic, heartbreaking photograph.

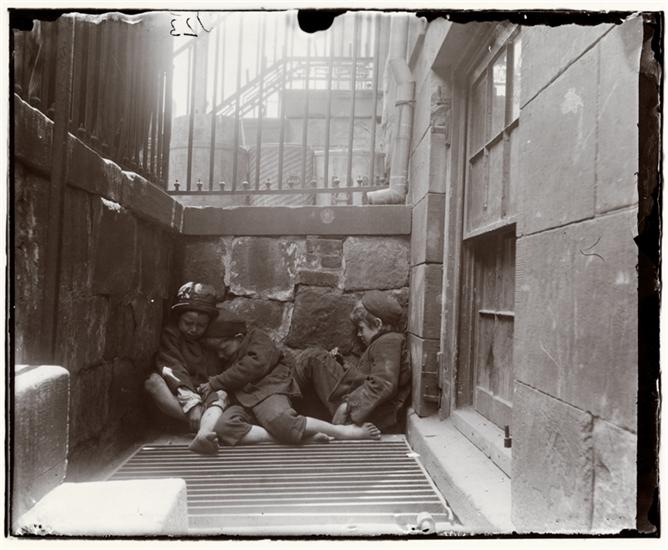

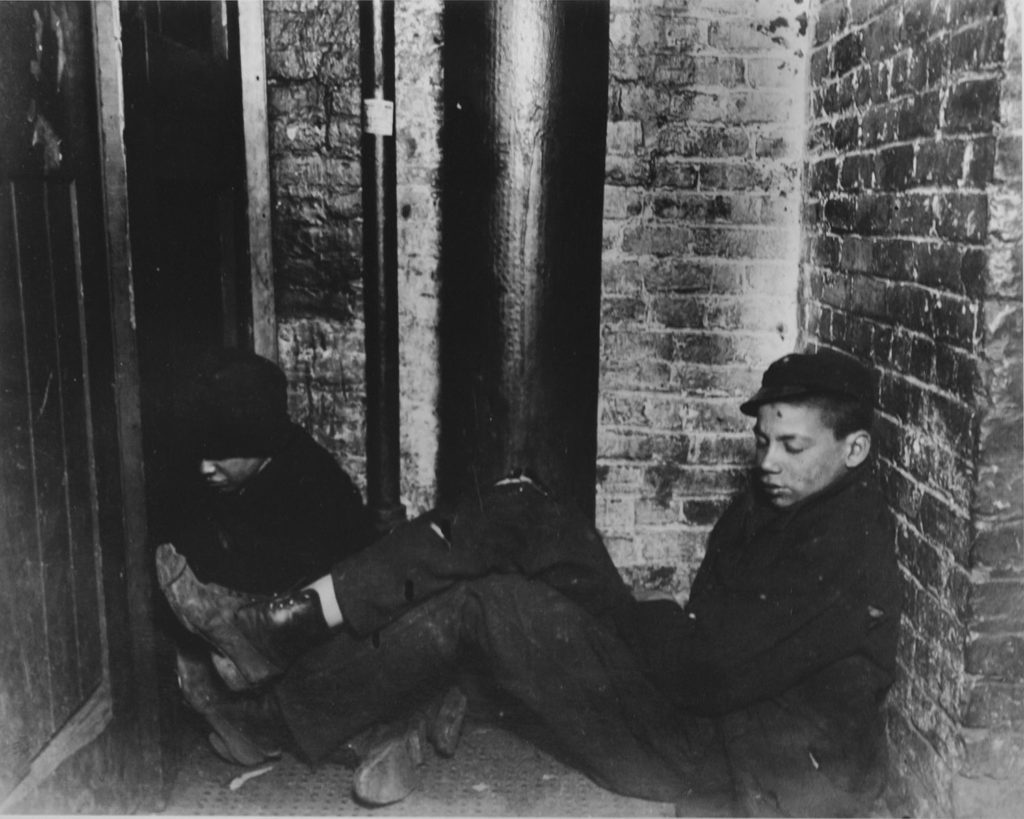

Called ‘Street Arabs in the Area of Mulberry Street‘, the image, taken in 1889, depicts three homeless boys sleeping over a heated vent on the bottom floor of a tenement (in the area of today’s Little Italy).

Their names are unknown. In the late 19th century, hundreds of children lived on the streets of New York, turned out of their homes or separated from their loved ones. Many actually did have loving families but living conditions in the tenements were so squalid that some chose to sleep on the street.

We have this image — and many, many similar ones — thanks to journalist and social reformer Jacob Riis.

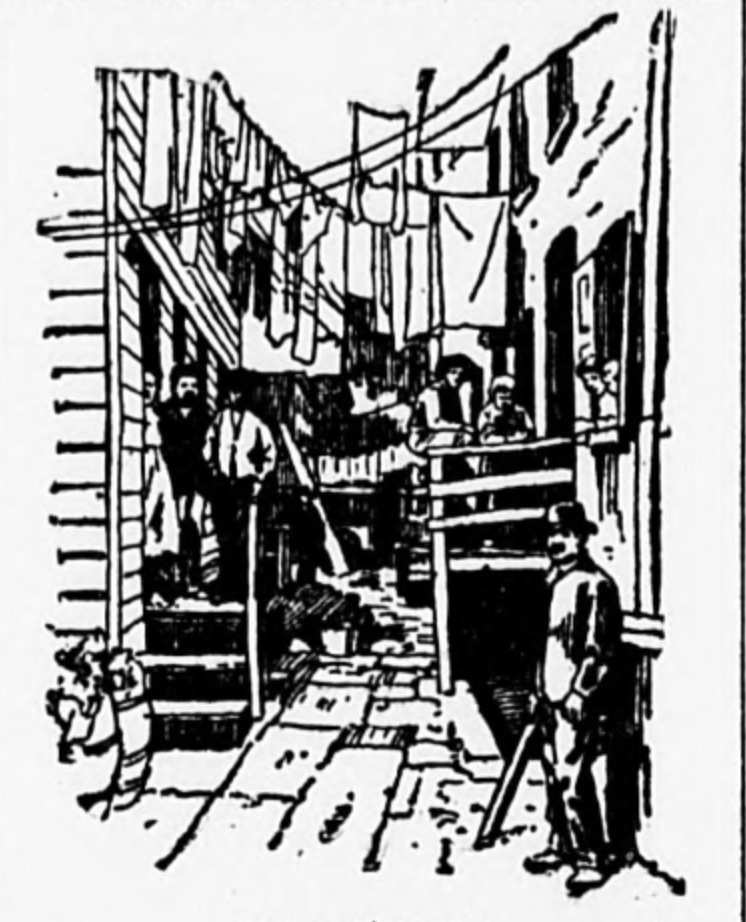

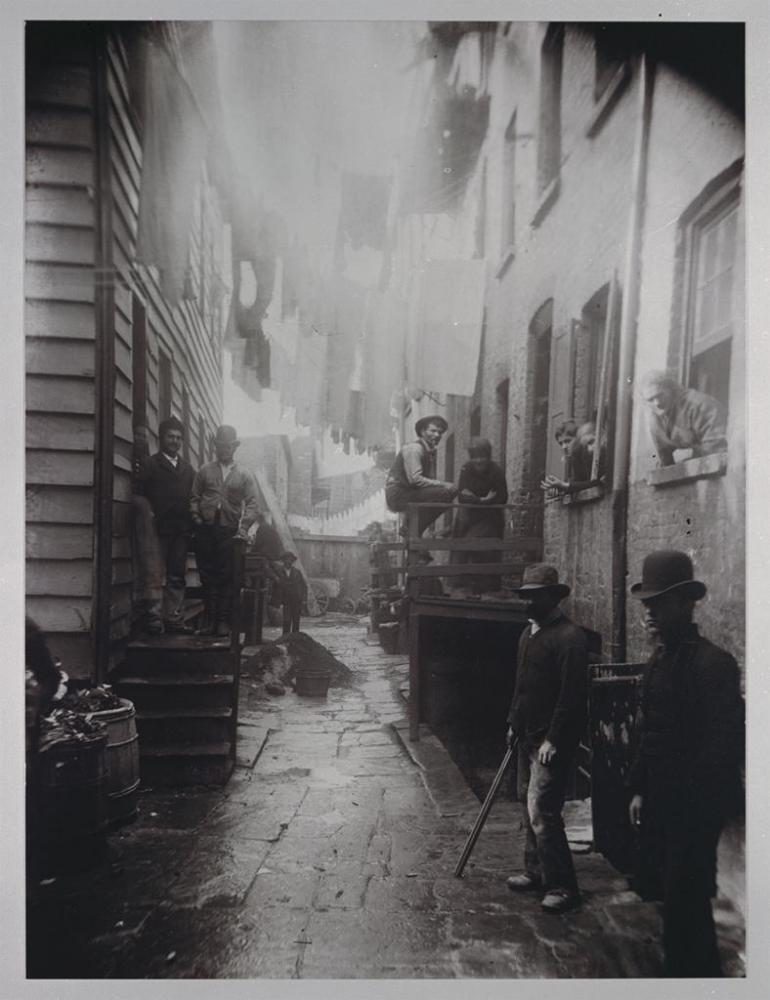

On February 12, 1888, Jacob Riis published his first investigation for the New York Sun, revealing the wretched conditions of New York’s worst slum neighborhoods by employing an experimental technology — flash photography. The startling pictures, by Riis and a team of other photographers, were at first rendered in line drawings, but the effect was nevertheless profound.

The entire article is available online but here’s the passage pertinent to the photograph above:

“Another outcropping of the benevolent purpose of Mr. Riis … is his showing of a touching picture of street Arabs in sleeping quarters which it must have taken a hunt to discover. These youngers have evidently spent their lodging money for gallery seats at the show and have found shelter on the back stoop of an old tenement house.”

Below: An illustration from the Feb. 12, 1888, newspaper, and the Riis photograph (of Bandit’s Roost) that it represents.

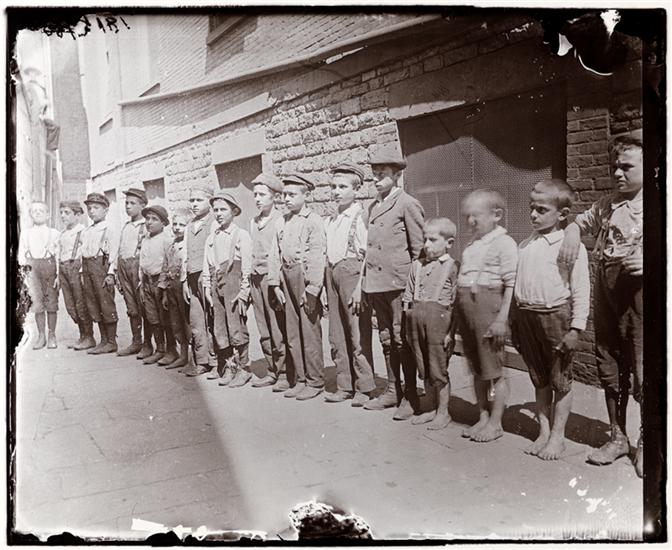

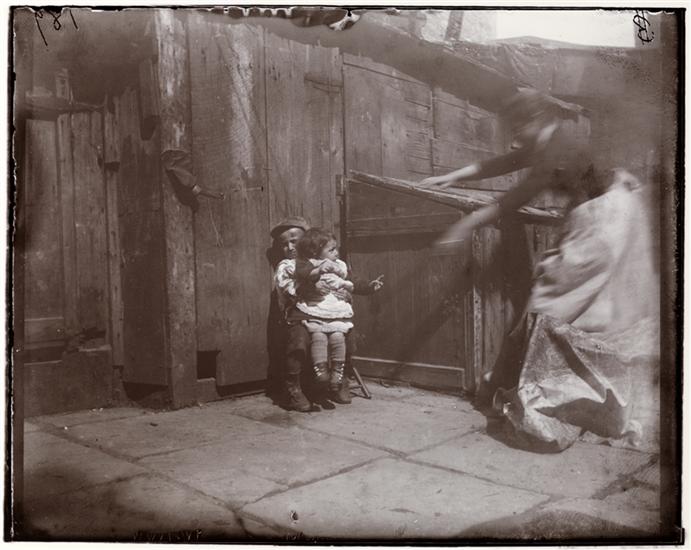

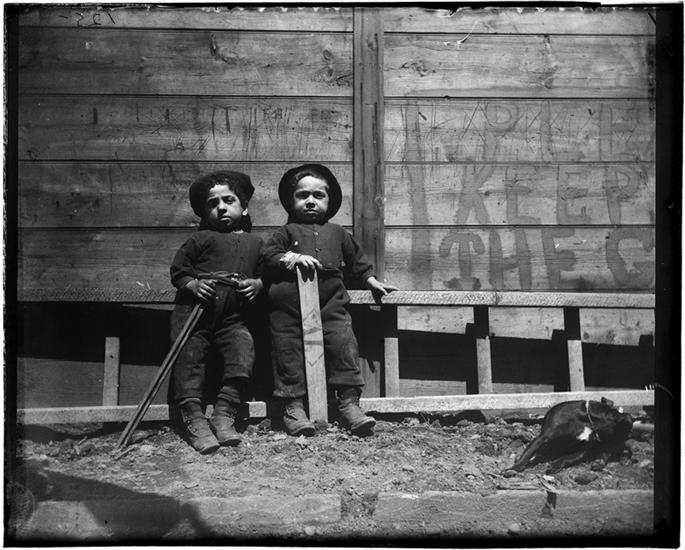

The pictures are more than social activism; they’re history themselves, the first flash photography ever to be used in this fashion. Riis was showing New Yorkers a vivid glimpse of poverty — orphans in the gutter, street gangs in the alleyway — using a technique that few were regularly exposed to apart from portraiture.

Riis never considered himself a professional photographer. Later in his career, he even farmed out the photographic work to others as he focused on writing and social activism. And yet modern photojournalism wouldn’t really be what it was today without his first forays into slums, opium dens and beer halls with his bulky and costly equipment. His early work influenced an entire field of social photographers seeking to prove the adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” (a phrase which debuted near the end of Riis’ lifetime).

His work would eventually be published as a book in 1890 — How The Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York — and Riis would spend the decade virtually proselytizing on behalf of the city’s needy.

In that book, he expounds upon the plight of the ‘street Arab’, aka street urchin.

“They are to be found all over the city, these Street Arabs, where the neighborhood offers a chance of picking up a living in the daytime and of “turning in” at night with a promise of security from surprise. In warm weather a truck in the street, a convenient out-house, or a dug-out in a hay-barge at the wharf make good bunks. Two were found making their nest once in the end of a big iron pipe up by the Harlem Bridge, and an old boiler at the East River served as an elegant flat for another couple.”

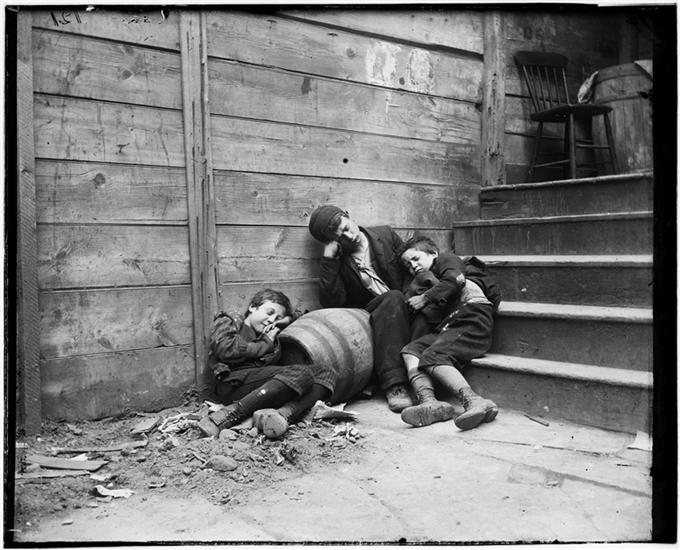

Below: Two boys asleep at 2 a.m. in the press room of the New York Sun newspaper.

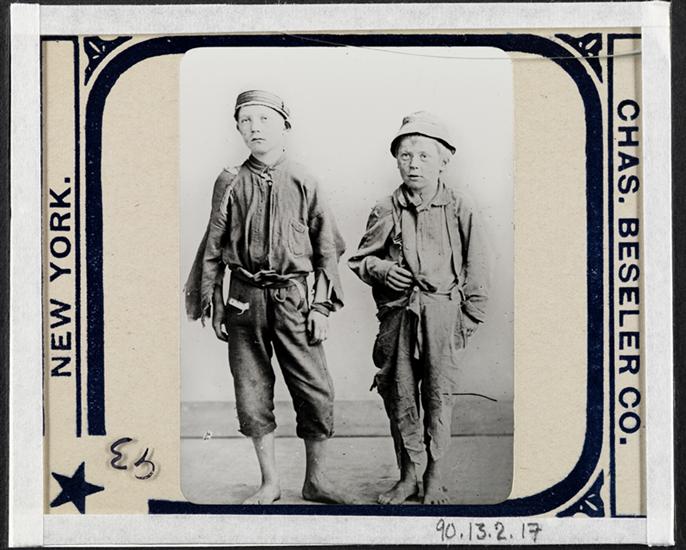

Most street kids are newspaper boys or bootblacks, fighting for scraps and a few pennies. In another section, Riis writes:

“We wuz six,” said an urchin of twelve or thirteen I came across in the Newsboys’ Lodging House, “and we ain’t got no father. Some on us had to go.” And so he went, to make a living by blacking boots. The going is easy enough. There is very little to hold the boy who has never known anything but a home in a tenement. Very soon the wild life in the streets holds him fast, and thenceforward by his own effort there is no escape. Left alone to himself, he soon enough finds a place in the police books, and there would be no other answer to the second question: “what becomes of the boy?” than that given by the criminal courts every day in the week.”

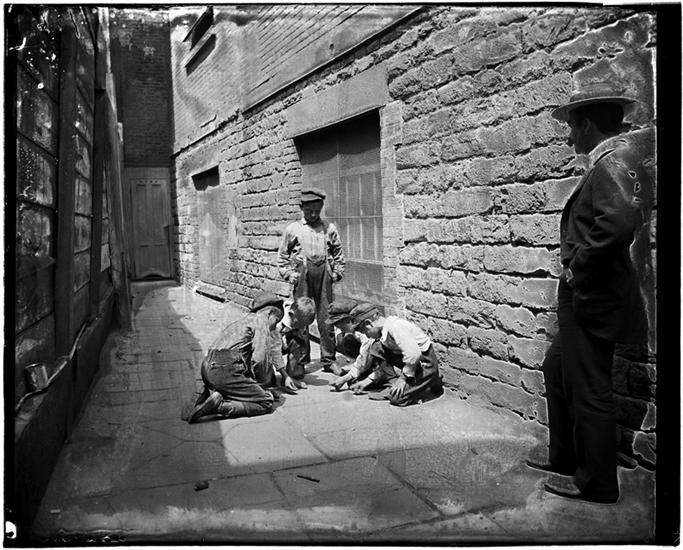

Below are more pictures of children on the streets of New York City in the late 1880s and early 1890s, taken by Riis and his associates, courtesy the Museum of the City of New York.

“Shooting Craps: The Game of the Street,” Bootblacks and Newsboys, 1894″ MCNY

This article excerpts a portion of our review of the Museum of the City of New York’s 2015 exhibition on Riis.

2 replies on “The harsh lives of New York City street kids, captured — in a flash — by Jacob Riis”

Would like information about the orphanage… does it still exist.

I am looking for records of my father’s stay in a home for boys circa 1937-1943. Dionisio J Amendola, don’t know name of home is the problem to get records. Can you help. His brothers, my uncles were also there. Sylvester and Vinny (or Vincent). Peter Amendola, pja204@yahoo.com