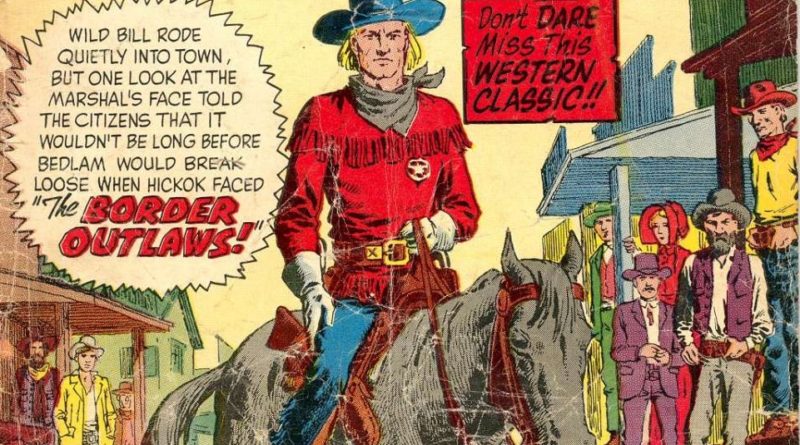

“Hickok was a celebrity. He was famous. He was feared. He was already a legend. It is estimated that over fifteen hundred dime novels were written just about Buffalo Bill Cody, beginning in 1869, when he was only twenty-three, into the 1930s, and during the early years. Wild Bill was in that category of iconic western hero. He had risen to the heights of both reputation and fabrication … and now the slow, inexorable descent began.” — Tom Clavin

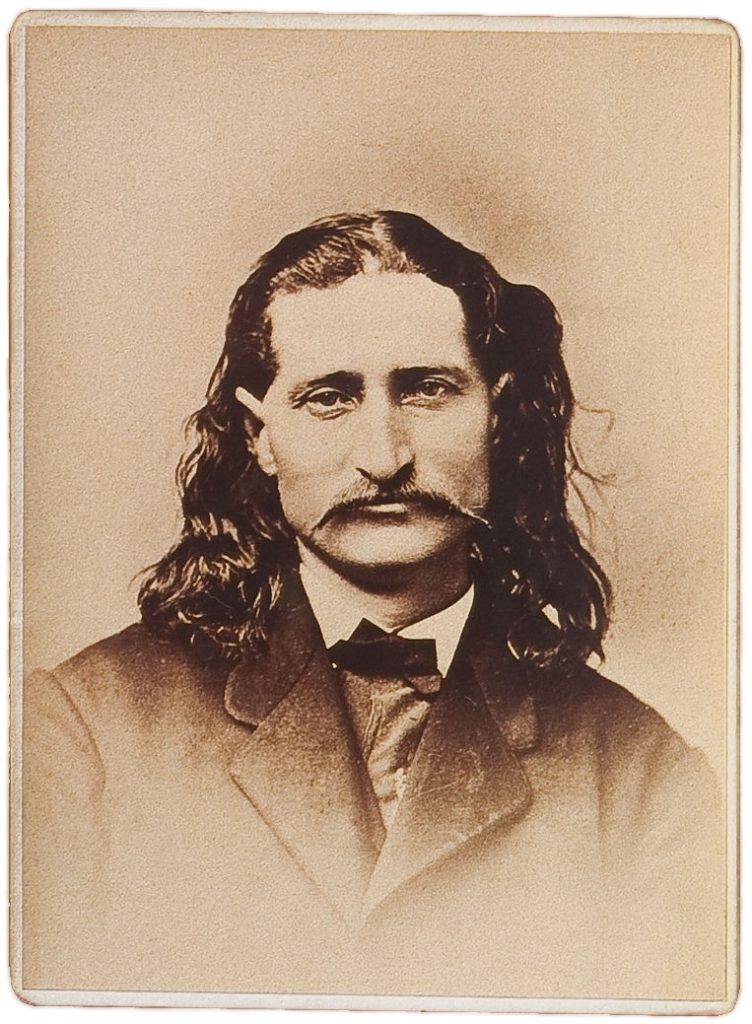

How do you write a book about a historical figure who seems more fiction than real? The Western folk hero Wild Bill Hickok lived a life that was thrilling, dangerous and brash, amplified by the fascinations of the American press into a virtual Western superhero.

by Tom Clavin

St. Martins Press/2019

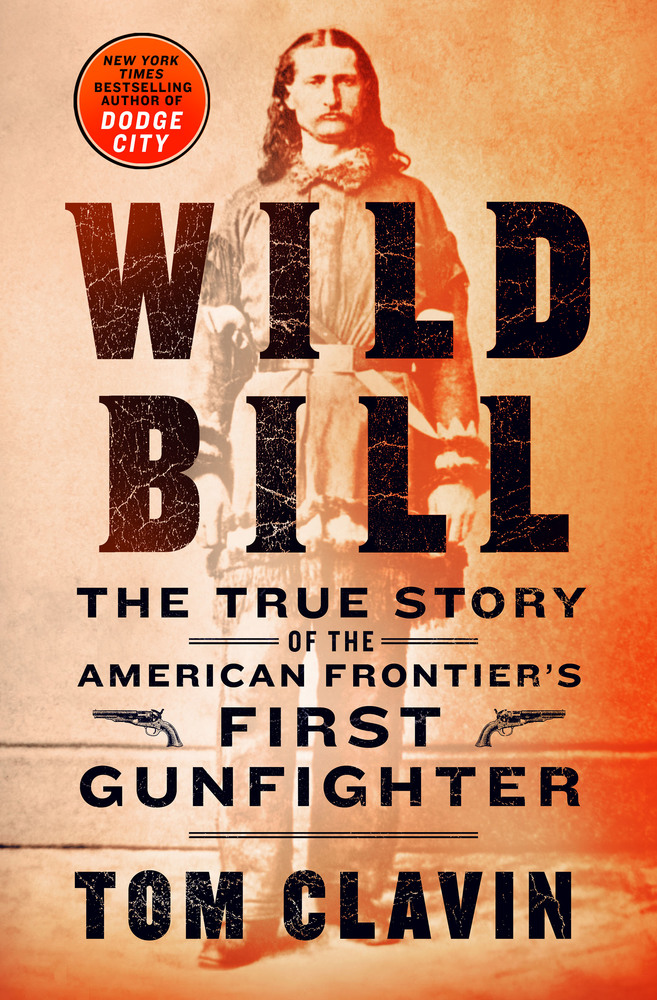

Tom Clavin’s Wild Bill: The True Story of the American Frontier’s First Gunfighter, a biography as frisky and unpretentious as its subject, attempts the noble task of walking back 150 years of mythology surrounding the Illinois man named James Butler Hickok, a drifter who wandered from job to job through Missouri, Arkansas and Kansas. During the Civil War, he worked as a wagon master and later a scout for the Union Army.

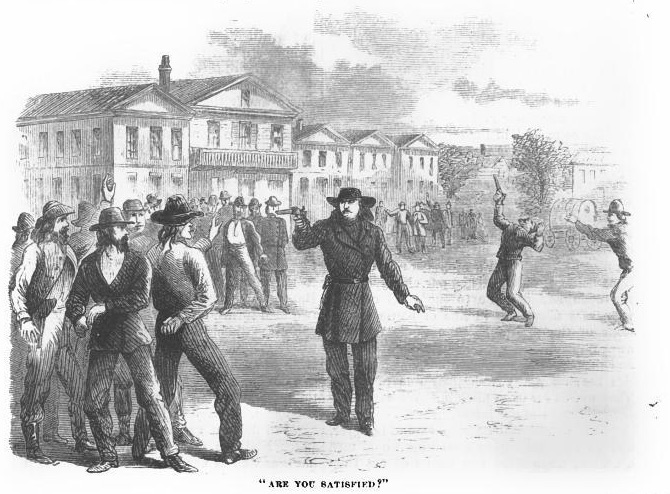

In 1865, he shot and killed the gambler Davis Tutt in the town square of Springfield, Missouri. This quick-draw duel — essentially over a pocket watch — took place in the early evening, not high noon. But whispers of this outrageously bloody event inspired a journalist named George Ward Nichols, working for New York’s Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, to profile Hickok.

It was in Nichols’ piece that Wild Bill Hickok — the fastest gun in the West — and indeed the genre of Wild West pulp fiction was born.

“[N]o single published piece catapulted a man on the American frontier more than Nichol’s article did for Hickok,” writes Clavin. With “the fertile imagination of a writer who could cash in on a sensational story and an outlet that offered that story to thousands of eager and mostly gullible readers, America had its first postwar frontier star.”

The attention only made Hickok more of a target with foolhardy men seeking him out in efforts to best the now-famous gunslinger. (It never ended very well for them.)

Clavin depicts an unruly but realistic western (or, more accurately, midwestern) landscape of chance encounters, brief romances and wide, arduous journeys. Yet even a hardened adventurer like Hickok would occasionally take a moment to bask in his fame.

In 1873 he joined his longtime friend ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody in the cast of a ham-fisted play Scouts of the Plains at New York’s Niblo’s Garden, becoming a major box office draw.

Today we might call him, um, difficult. “Hickok felt like he was risking his integrity and dying a bit with every performance because he became further convinced that acting was a foolish occupation. One night … he took one of his real pistols and shot out the spotlight that had been fixed on him. The audience applauded the dramatic reality of the production as well as Hickok’s famous marksmanship.”

On August 1, 1876, Hickok was murdered during a poker game in Deadwood, a frontier town in the Dakota Territory, cutting short any future stage performances but securing his position in the pantheon of Wild West mythology.

At top: An issue of the 1964 comic book Wild Bill Hickok #12, published by Super Comics

1 reply on “WILD BILL: The real man behind a Western legend — and a reluctant Broadway stage star”

What was a real shame is that I lived in Springfield Mo from 1963 to 1971 and never during that time in all of my grade school and high school history or any history classes was there any reference to Wild Bill Hickock and the shooting on the square. This was such a major event in springfields history and that it was never even mentioned. Now as an adult the city finally realizes the historical importance.