The first official patient of the Free Hospital and Dispensary for Animals at 350 Lafayette Street, under the care of veterinarian Bruce Blair.

The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) was formed in 1866 by philanthropist Henry Bergh. Eight years later, he helped co-found the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

Yes, animals came first. Animals were not only better understood than children, they were instrumental to the daily flow of the city. Almost every vehicle on the street was horse powered. The skills of animal husbandry and veterinary medicine were adequately developed in a country that was mostly rural, while the psyches of the human adolescent were only just being appreciated.

Yes, animals came first. Animals were not only better understood than children, they were instrumental to the daily flow of the city. Almost every vehicle on the street was horse powered. The skills of animal husbandry and veterinary medicine were adequately developed in a country that was mostly rural, while the psyches of the human adolescent were only just being appreciated.

At right: Mrs. N.H. Barnes and her dog Mousie, circa 1910-1915, courtesy Library of Congress

And don’t underestimate the power of the upper crust and their favorite luxury items — exotic pets. New Yorkers were perhaps empathizing with animals, if not exactly knowing how to treat them.

After all, the menagerie of the Central Park Zoo was created from the bad decisions made by wealthy people, regretting their decisions in bringing unusual animals into their homes. In 1907, New York even experienced a bit of a monkey craze, with dozens of small primates becoming adorably mischievous fashion accessories.

Animal rights became an interesting tangent of New York’s progressive movement, a focus on the well-being of four-legged creatures that culminated, one century ago this week, in the opening of the Free Hospital and Dispensary for Animals (at 350 Lafayette Street), the first institution of its type in the United States.

Like many progressive institutions of the day, the animal hospital was a life’s ambition for a wealthy socialite — in this case, Ellin Prince Speyer, the wife of railroad banker James Speyer (founder of the Provident Loan Society.)

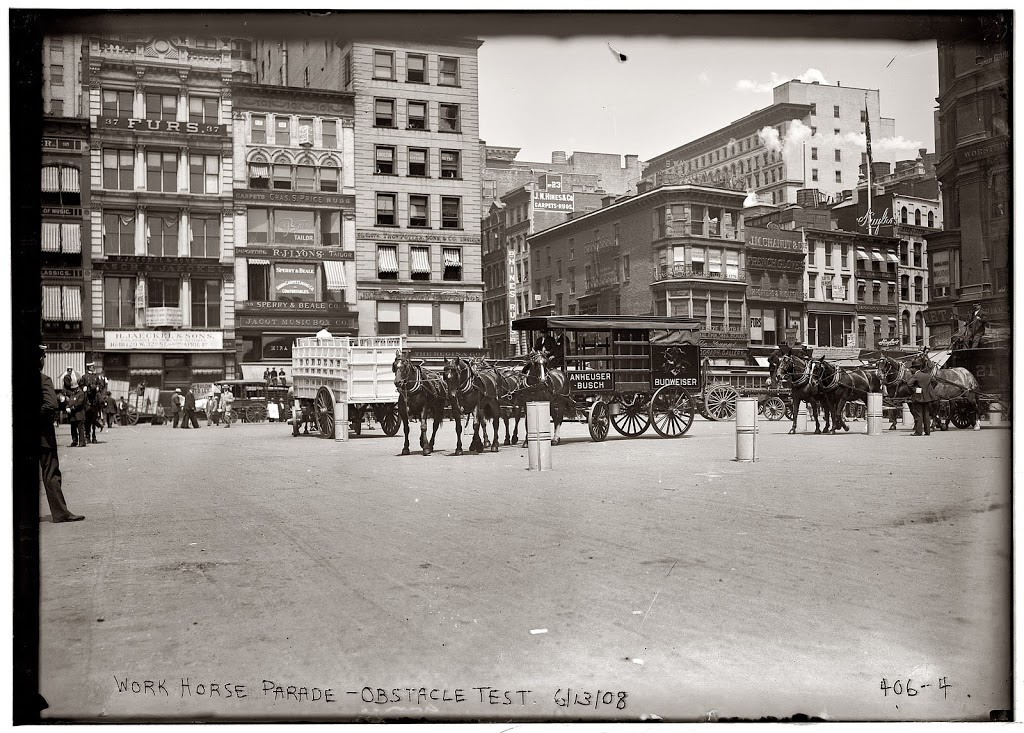

Above: Work horses compete in an obstacle course in Union Square, during the Work Horse Parade of 1908. Picture courtesy Shorpy

Speyer formed a Women’s League of the ASPCA in 1906 and quickly organized public displays that would bring attention to the plight of work animals. The following year, on Memorial Day, she organized the first annual Work Horse Parade with contests and exhibitions, all in an effort to bring attention to the condition of horses on city streets.

People were given prizes if their old horses were in good shape! “An effort has been made to induce the peddlers and hucksters of the city to enter,” said the New York Times.

The Women’s League provided watering station for horses during the summer and even free “horse vacations,” renting a farm in upstate New York for the care of older animals.

But the League was concerned with the health of all animals, not just horses. (Indeed, the New York Sun takes note of Mrs. Speyer’s favorite animal — “the life saving Japanese spaniel Trixie.”) Members visited area schools to lecture on the proper care and feeding of pets, speaking to the young owners of dogs, cats and birds.

They believed that beneficence to the animal kingdom was a signal to a healthy, moral household. “You don’t find wife-beaters who are fond of pets and lovers of animals,” said the League in an editorial in 1912.

This sophisticated devotion to animal care was considered truly unique. For instance, when an impressive animal clinic opened at Cornell University in 1911, the New York Times replied with the headline, “Where Sick Animals Are Cared For Like Humans.“

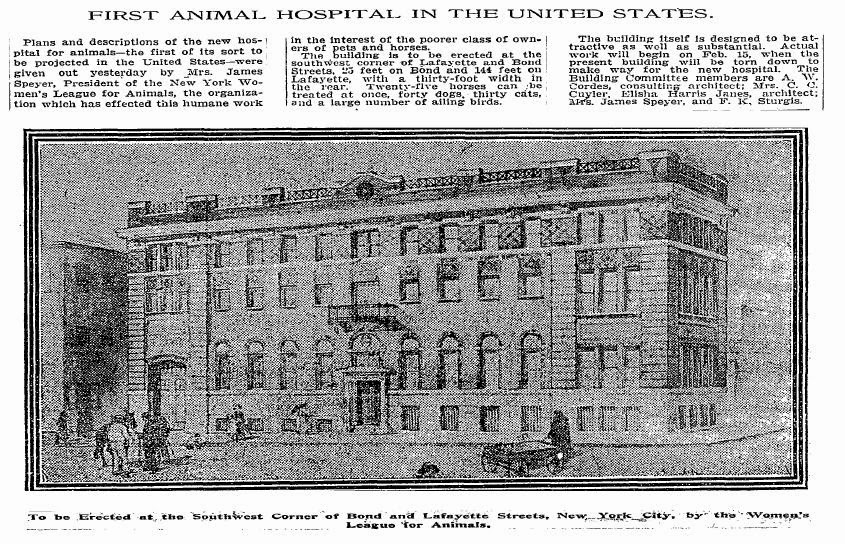

From the New York Times, February 1913

Speyer opened a small animal clinic in New York that same year, but it was woefully inadequate to the needs of New York’s animal population. So, with the help of lavish benefits and donations from other wealthy families (including many of her banking friends), the Women’s League raised $50,000 and opened up a proper animal hospital on March 14, 1914, the first animal hospital of its kind in the United States.

The five-story building is still there today. New York’s first free animal hospital could accommodate fifty horses and 150 cats and dogs. “There are also operating rooms where every modern appliance for animal surgery is at hand.” [source]

Horses were mostly kept and operated upon on the second floor. But a rooftop garden accommodated the most sickly horses in need of fresh air and sunshine, lifted there by a large, state-of-the-art elevator. I suppose it was also used for patients from the third floor — dogs, cats and birds. Autopsies were also conducted on the roof, and dead animals were disposed of in a basement incinerator. (The Times actually calls it ‘the death room.’)

Perhaps most curious of all — an entire floor was given over to a new apartment for the hospital’s lead veterinarian Dr. Bruce Blair (pictured at top) and his new bride.

On its opening on March 14, Speyer showed the waiting dignitaries a mysterious envelope which contained a $1,000 bill, anonymously donated for the purposes of buying the hospital’s first animal ambulance.

Perhaps the hospital’s most famous patient on opening day was not not a horse, but a green parrot named Abe, who was a bit of a minor film star in 1914. I believe this was the star of the 1914 Oliver Hardy film The Green Alarm.

Today, the Animal Medical Center traces its lineage to this first animal hospital and to Speyer’s organization. It moved to its current location on the Upper East Side in 1962. (You can read more about their history here.)

Here’s the building as it looks today:

1 reply on “America’s first free animal hospital, at 350 Lafayette Street, with a roof garden for sick horses”

That sounds like an animal hospital that was ahead of its time. Good proper treatment of animals is something people have been striving for. People love their pets a lot and want to take good care of them.

http://www.metroanimalhospital.ca/about_the_clinic.html