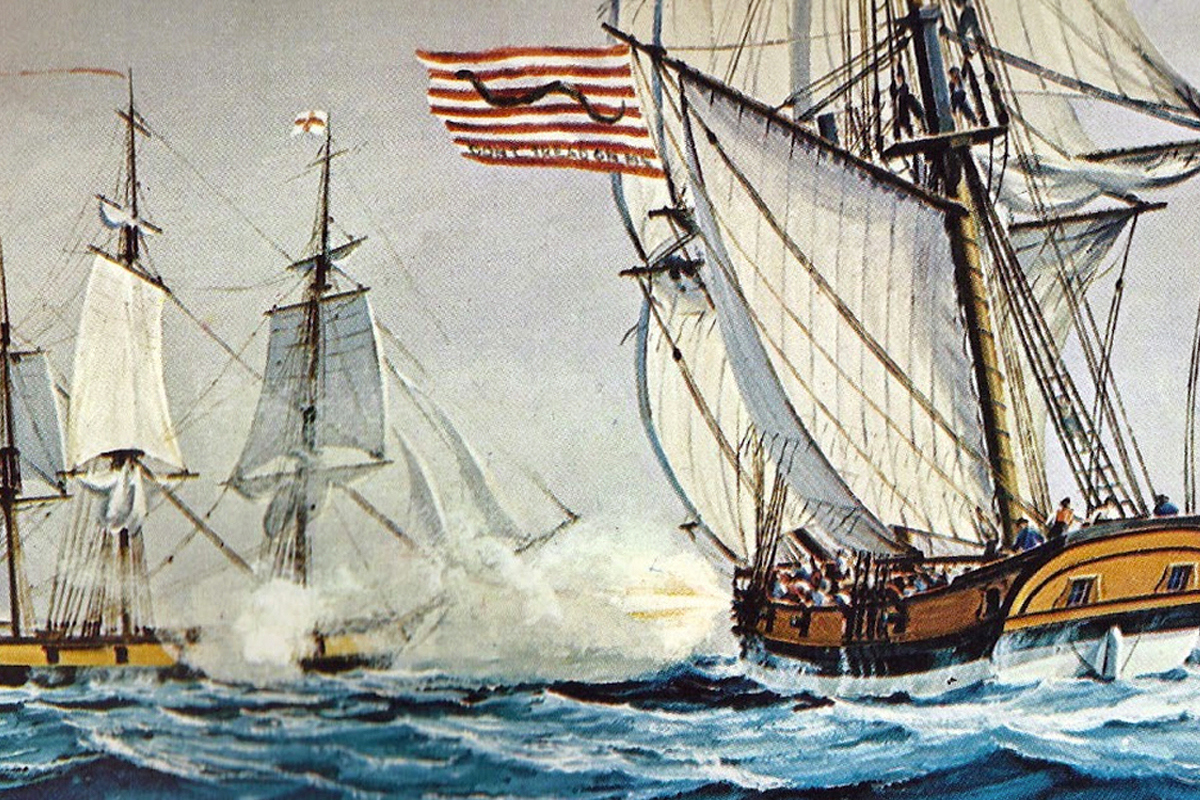

Privateers have been much maligned in history, so much so that perhaps you didn’t realize their important role in gaining America its independence from Great Britain.

If your first image of a privateer is a sinister, blood-thirsty madman with a knife in his teeth and a skull on his sails, you’re probably thinking of a culturally exaggerated version of a pirate.

But if your next image of a privateer is a tanned and tattooed sailor with a sword and a ship full of stolen treasure — well, now you’re getting closer to the reality of a privateer’s life.

REBELS AT SEA

Privateering in the American Revolution

Eric Jay Dolin

Liveright/WW Norton

There may be no better read for an American Revolution history lover this summer than Eric Jay Dolin‘s latest Rebel At Sea, a look at the forgotten role of the privateer during America’s battle for independence.

Because of their similarity with pirates — criminals who scoured the sea to pillage for personal and malevolent gain — privateers are often ignored in the annals of history, especially in events that have been heavily sanitized of uncomfortable truths like the American Revolution.

As Dolin reveals, privateers were a bit like a shadow navy; indeed they existed in the colonies before there was an actual American naval force.

What set them apart was an authorized letter of marque, a license from the government to capture vessels from enemy nations and take their possessions. The haul would then be sold and, generally speaking, split between the crew and the letter’s issuer.

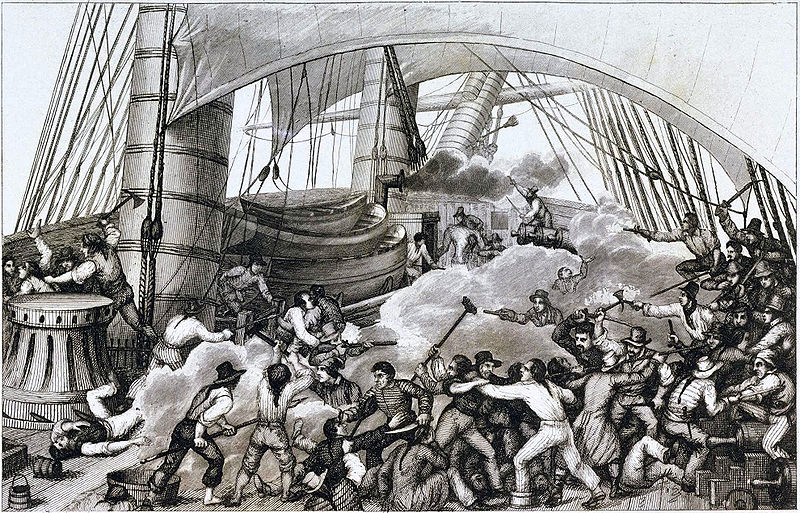

At first a tool for defense by individual colonies, the American Congress soon passed a resolution employing privateers — months before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. “Privateers were free to capture any British vessel,” Dolan writes, “not just those that were delivering supplies to British forces in America. (Later, neutral ships carrying good bound for British use were also deemed acceptable targets).”

Revolutionaries like John Adams were enthusiastic proponents of privateering. “Thousands of schemes for privateering are afloat in American imaginations,” he wrote his wife Abigail. “Out of these speculations many fruitless and some profitable projects will grow.”

Dolin describes the life of the average privateer as far less glamorous than that which we might normally prescribe a swashbuckler. Rebels at Sea does highlight some of the privateering triumphs of the Revolution — from John Greenwood, a young privateer who later became George Washington’s dentist, to the many privateering whaleboats.

In a dark local angle, British-occupied New York launched their own counter privateering vessels “with the most fervor and success” and thousands of captured American privateers were imprisoned in the loathesome holds of Wallabout Bay prison ships.

There are men whose sacrifices should also be remembered during Independence Day celebrations this year. And Dolan’s Rebels at Sea presents a great introduction to this hidden corner of American history