Out in the cold: Llewyn Davis gets no respect. Pic courtesy CBS Films

NOTE: This article contains minor spoilers for the film Inside Llewyn Davis, so proceed with caution if you have not yet seen the movie!

The latest movie by Joel and Ethan Coen, Inside Llewyn Davis, meanders through a coolly tinted rendition of New York in 1961, depicted as a chilly and even mystical place and time. Davis (the brilliant Oscar Isaac), our scruffy hero, is introduced in a beautiful musical number down at a basement basket house in Greenwich Village. Certainly this singer is about to be discovered? Or perhaps he’s already a star? Quite the opposite, in fact.

Inside Llewyn Davis is a trademark Coen brothers movie, rarely straight-forward in narrative, with a bounty of great songs allowed to linger and finish. As in O Brother Where Art Thou, there’s a mythical road trip with kooky characters, but the movie eventually returns to New York. You’ll be happy to know that the second most important character in the film is probably a cat.

The movie doesn’t need to be so historically detailed — it feels mostly like a dream — but thankfully the production design takes its cues from places that actually existed. Here’s a few significant historical New York details that I noted from a first pass at the movie this weekend. I certainly might have missed something while scribbling notes in the movie theater, so please don’t hesitate to leave a comment if you have a correction!

Breakfast at Tiffany’s — The film, set in 1961, makes a clever nod to a movie that was actually released that year, Breakfast At Tiffany’s. In both movies, an unusually named orange cat retreats down a fire escape, leading to a frantic search through the streets of New York. In Breakfast, the apartment is in the Upper East Side; in Llewyn Davis, the Upper West.

The current film, however, seems to reflect the more melancholy ending of Capote’s original novella, not the bright-and-happy ending of the Breakfast film. I imagine that the Coen brothers’ screenplay might have been inspired by this line: “It took weeks of after-work roaming through those Spanish Harlem streets, and there were many false alarms — flashes of tiger-striped fur that, upon inspection, were not him. But one day, one cold sun-shiny Sunday winter afternoon, it was.”

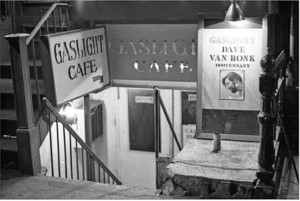

The Gaslight Cafe — One of New York’s greatest (and smallest) venues for folk music in the 1960s, the Gaslight was located at 116 MacDougal Street. Today its the low-key bar 116. (Hey, would you prefer it be a Chiplotle?) Along with Cafe Wha? and the Village Gate, the Gaslight provided stages for Greenwich Village’s burgeoning folk music scene.

A pivotal scene near the end did not actually take place at the Gaslight, but instead over at another seminal music venue, Gerde’s Folk City.

Dave Van Ronk — The character of Llewyn Davis is loosely based (depends on your definition of loosely, I guess) on this regular of the Village folk scene, one who never broke through in the same way as his peers. Like Davis, Van Ronk grew up in Queens, but in Richmond Hill, not Woodside, as the film depicts for Davis.

Kettle of Fish — Also seen along the streets next to the Gaslight is the tavern Kettle of Fish, back when it was on MacDougal Street. Today, Kettle of Fish is located on Christopher Street, on the site of the old Lion’s Head bar, a writer’s hangout and favorite of Norman Mailer‘s back in the day.

At right: The original Kettle of Fish in the 1950s. Photo courtesy Ephemeral New York

Both the Lion’s Head and Dave Van Ronk are featured players in a bit of Christopher Street history — namely, the Stonewall Riots. Van Ronk was celebrating his birthday at the Lion’s Head in the early morning of June 28, 1969, when the police came to shut down the mob-operated gay bar, located nearby. Van Ronk got involved in the riot himself, allegedly throwing coins at the police. The singer was then beaten by police and dragged into the Stonewall bar.

Caffe Reggio — This dark and weathered old cafe across the street from the Gaslight is a Village treasure, opening in 1927 during the days when its neighbors were speakeasies. It’s one of the few places depicted in Llewyn Davis that’s not only still open today, but pretty much in the same condition, at least judging from the last time I had a cappuccino here. According to Mitch Broder, “Reggio is the mythic Village hangout that’s not a myth: It would like like it did eighty years ago if it weren’t for the customers.”

And Calvin Trillin, in a New Yorker article in 1963, described Reggio as a place “whose ornate espresso machine and quiet interior seemed to belong to some other neighborhood.”

Rocco Ristorante — This grizzled old eatery, dating from 1922, was located at 181 Thompson Street, its fantastic old neon sign still a treasured mark of the Village. It closed in 2011, but recently reopened as a restaurant again as Carbone. (Picture of sign courtesy Jeremiah’s New York)

Washington Square Park — It wouldn’t be a folk movie without a scene here, the heart of the 1960s music scene. However, in 1961, it might have been a rather tense time in the park, and not welcoming to folk musicians at all. When the park association closed the park to “roving troubadours,” the musicians fought back. On April 9, 1961, thousands of artists and their supporters flooded the park, an outpouring that became derisively known as the Beatnik Riot. (You can hear more about the riot and the history of Washington Square Park in my walking tour on the subject.)

Columbia Records — The label which would later sign Bob Dylan is featured briefly in the film. In 1961, their big star would have been Andy Williams, a far cry from the sounds of coffee-shop culture. Columbia’s well-known offices in the CBS Building, designed by Eero Saarinen and nicknamed Black Rock, would not have been completed yet, so this scene would have been in Columbia’s old offices at 485 Madison Avenue.

George Washington Bridge — This is the location of a off-screen suicide and a subsequent off-color joke about the rarity of such suicides at this location. As we know from modern news events, however, the GWB is actually a frequent site for suicide attempts. Two years ago, a staggering 43 people reportedly tried killing themselves from this spot. And I can’t help but think of another great movie musical (Saturday Night Fever) which also features a tragedy off another large New York bridge.

New York Subway — For a film planted in the Village, there’s a lot of travelling around on the subway — to the Upper West Side, to downtown Varick Street, even Queens. According to the 1959 subway map, Davis rides the IRT’s Flushing line to Woodside/61st and the Broadway local line to Varick.

Fred Harvey — The most unusual scene in the movie takes place at the Fred Harvey roadside restaurant inside the Illinois Tollway oasis in northern Illinois. It’s here that I want to plug one of my favorite podcasts, the American history show Backstory, as just last week they featured a story on Fred Harvey and his ubiquitous chain of restaurants. You should check out their show ‘Three Squares’, on the history of mealtime in America, where they discuss Harvey’s innovations as perhaps America’s first chain-restaurant mogul.

2 replies on “Inside ‘Inside Llewyn Davis’, a gauzy, surreal homage to 1960s New York bohemian life”

”

”

I don’t agree, look at http://www.wired.com/2016/02/californium-philip-k-dick-homage/

Sincerely, Sha

Quite unnerving IMO, for the Coen Bro’s to paint such a grim view of Greenwich at this time. These artists and their friends were on fire with creativity, burning with a desire that seems so foreign today and they were alive and bursting with electricity to blaze their paths through this world. I’m sure life was tough at times but in every autobiography I’ve read from here ( Dave Van Ronk specifically) this slit your wrist mood is pure horse shit. It would have been unthinkable in his book……..he would have laughed at this film and definitely would have seen straight through the angular BS