KNOW YOUR MAYORS A modest little series about some of the greatest, notorious, most important, even most useless, mayors of New York City. Other entrants in the Bowery Boys mayoral survey can be found here.

Mayor George Opdyke

In office: 1862-1863

The wealthy merchant and politician George Opdyke died on June 12, 1880, attended to by his family from their lavish home at Fifth Avenue and East 47th Street, just a few blocks from where the violent Draft Riots had ignited back in 1863.

In the 17 years since those terrible days, New York had grown mightier with vast wealth, in an explosion of prosperity that would inaugurate the Gilded Age. But while the scars of the Draft Riots had faded from the city streets, they never quite faded from Opdyke, who had been mayor of New York during the violent outbreak.

In the 17 years since those terrible days, New York had grown mightier with vast wealth, in an explosion of prosperity that would inaugurate the Gilded Age. But while the scars of the Draft Riots had faded from the city streets, they never quite faded from Opdyke, who had been mayor of New York during the violent outbreak.

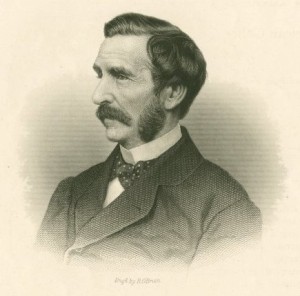

At right: George Opdyke, in a photo taken by Matthew Brady

Some of the violence that week in July had been directed towards Opdyke, one of the most prominent Republicans in a city of Democrats. His former home at 57 Fifth Avenue had been attacked twice by rioters. He was considered the face pro-Lincoln, pro-war, and, thus, pro-abolitionist forces in New York

Yet had it not been for the institution of slavery in the South, Opdyke might never have even made his fortune.

George Opdyke was born to a large New Jersey farming family in 1805, working his way from the fields to the classroom, becoming a young school teacher at an early age. Like so many teenagers in the early 19th century, job opportunities out West spoke to his sense of adventure. With $500 in their pockets, Opdyke and a friend settled in Cleveland, Ohio, opening a clothing store and tailor for workers of the newly constructed Erie Canal.

Opdyke soon found a more profitable application for his young business — the high mark-up manufacturing of cheap slave clothing. He moved to New Orleans and began an incredibly profitable plant there, making inexpensively produced clothing for the plantations of the deep South.

In fact, Opdyke became so successful that, in 1832, he moved to New York to open a larger clothing factory on Hudson Street. According to historian George Lankevich, Opdyke “built the city’s first important clothing factory, selling his goods largely to southern plantations and creating the basis of a new industry.” It was the first large-scale, ready-to-wear clothing establishment in New York, soon employing thousands; so, yes, this is how the New York fashion industry begins.

Below: Brooks Clothing Store in 1845, a rival of Opdyke’s clothing business. Opdyke would have some rather controversial connections for Brooks Brothers during the Civil War. (NYPL)

And a successful political career begins as well. By 1846, Opdyke, now a millionaire and a well-connected member of mid-19th century New York society, entered a life of politics.

Interestingly, he was originally associated with the Free Soil Party, an early anti-slavery effort, illustrating how businessmen often separated certain moral beliefs from their business practices. (Early on, he would become one of Abraham Lincoln’s most ardent supporters.) The Free Soilers were soon be incorporated into the burgeoning Republican Party, and Opdyke’s first appearance in New York state assembly, in 1859, was as a Republican.

That same year, Opdyke became the Republican’s best chance at winning the mayor’s seat in New York. However, he vied for the job with two other seasoned politicians — unscrutable Democrat Fernando Wood and former mayor and sugar king William Havemeyer. Thanks to machine politics and the uncertainty of war with the South, Wood prevailed that fall, becoming mayor of New York at the start of the Civil War. (I have an entire podcast on Wood’s roller-coaster career in politics.)

But tides would change in Opdyke’s favor. Pro-Union sentiment surged through the nation and in New York City by the start of the war. And by the time of the next mayoral election in 1861, situations were ideal for a Republican to take charge.

It helped that Democrats were divided — Tammany Hall went with C. Godfrey Gunther, while Wood formed his own alternative political machine Mozart Hall. But it was Opdyke that prevailed, although barely. He beat Gunther by a whopping 613 votes. (But he did beat Wood in Wood’s own ward. That must have felt good.)

Part of Opdyke’s appeal at that moment was his deep connections to the Lincoln administration. When the flags were waving in New York, Opdyke was an ideal representative, encouraging support for the war, hosting troops in the city, raising money for the effort. But when enthusiasm for the war withered, so did Opdyke’s reputation.

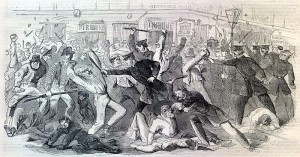

Below: The draft riots, which paralyzed New York in July 1863

Opdyke’s unwavering support for the draft backfired severely in the summer of 1863. When New Yorkers took the street on July 13, 1863, burning the draft offices and taking out their anger on black citizens and prominent Republicans, Opdyke topped the list of most despised New Yorkers. He had very little power to quell the violence; the police department was placed under state control, and state militia had been called away.

While his home was nearly destroyed, it was his political reputation that took the greatest hit. At first, he had vetoed a plan by the Common Council to pay for substitutes for any drafted New Yorkers. But a month later, working with Tammany Hall, he essentially endorsed a similar bill to avoid more violence.

This saved New York, but it did not save him. On election day, that December in 1863, he was replaced with the Democrat Gunther, whom he had narrowly beat just two yeas before.

His woes weren’t quite over. A political feud with newspaper editor Thurlow Weed revealed some unpleasant information about Opdyke in the press. “[H]e had made more money out of the war by secret partnerships and contracts for army clothing, than any fifty sharpers in New York,” claimed the irate newspaper editor.

At right: Opdyke in later life (NYPL)

Opdyke had profited handsomely from the war through his own clothing plant and in deals with rival clothing manufacturer Brooks Brothers. Opdyke took Weed to court for libel in December 1864, but the jury essentially exonerated Weed, delivering an indecisive verdict “as to whether Weed should pay nominal damages of six cents, or be acquitted.” [source]

In later life, Opdyke took up banking with his sons, representing the concerns of various railroad companies. He “retired a few months before his death with a large fortune.” [source]

After his death, the Opdykes would sell their house to railroad tycoon Jay Gould.