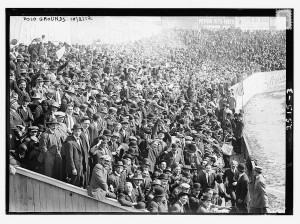

Above: the crowds at the Polo Ground for Game One. Many of these same people were certainly on hand for the fateful Game Four.

One hundred years ago today, in the frantic fall of 1912, even as the nation was in the midst of an intense three-way race to elect a new president, New Yorkers and Bostonians were overwhelmingly — perhaps even unnaturally — distracted. For the first time ever — since the introduction of the World Series baseball championship in 1903 — a New York club was finally battling for ultimate victory against a Boston team.

The two cities had been in perpetual competition for most of their history; organized sport merely provided a formalized outlet to rally regional pride. [For more information, check out my article on the roots of the Boston-New York rivalry.]

The two cities should have already met on the diamond for the 1904 World Series, as the New York Giants were victors of the National League, while the Boston Americans led the American League. Boston clutched that particular victory by defeating another team from New York, the upstart New York Highlanders (who later became the Yankees).

However, the Giants refused to play the Americans in the World Series, a tantrum thrown by managers aimed at the ‘inferior’ American League (originally the junior circuit). Rules were changed the following year to make championship play between the leagues compulsory.

Eight years later, in 1912, the New York Giants were matched against the same Boston team under their new name — the Boston Red Sox. No hesitation this time around. They were undeniably the two best terms in America, and both clubs were determined to win the title for their home cities.

For this Series, teams shuttled back and forth between Boston’s Fenway Park and New York’s premier baseball venue of the day, the Polo Grounds.

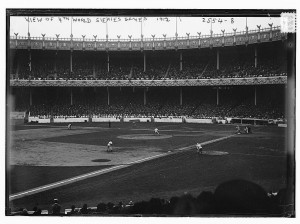

Above: A view of the Polo Grounds during Game Four, absolutely packed to the rafters

Game One, played at Polo Grounds, went to Boston. Game 2, at Fenway, lasted so long — eleven innings — that the game was declared a tie on account of darkness. (Night baseball wouldn’t be played at Fenway until 1947!) New York then won the second game at Fenway the following day, tying up the match.

For a fourth consecutive day of baseball, the teams were to return to the Polo Grounds (located at W. 157th Street and 8th Avenue). New Yorkers had the momentum, anxious to build upon their triumph in Game Three. Both teams, already exhausted, packed into trains and headed back down to New York, arriving that evening at Grand Central. The Giants headed to their respective homes in the city, the Red Sox to their accommodations at Bretton Hall on Broadway and 86th Street.

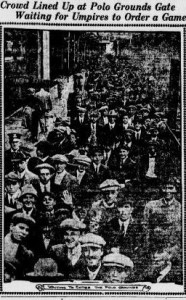

Fans were already so excited for Game Four the next day that some were already lined up at Polo Grounds before the players even arrived in New York.

Unfortunately, one curious obstacle threatened to ruin everybody’s good time: mud.

The Polo Grounds were an uncovered grass field and throughout most of that evening it was pelted with rain, turning this fairly new ballfield (re-built in 1911 after a fire) into what the Evening World called “a mysty mystery” of gray and yellow-brown fog. The infield was protected by a tarp, but the outfield was battered by the elements. Was it in any condition for a major baseball game?

Commissioners failed to decide that morning whether the game could commence, and baseball fans grew restless. Well, that’s an understatement. Giants fans were enraged. “[T]he lynching-hungry scream of an infuriated mob” filled the air around the stadium, as thousands more joined the brave few still in line from the night before should the field reopen.

An Evening World reporter followed a groundskeeper along the soggy field who lamented, “They can play on it, all right … Sure, they can play, but oh, me poor grass!”

Umpires were given a police escort into the Polo Grounds at 11 a.m. to inspect the condition of the field. By that time, the mob was practically foaming at the mouth, with “a blood-curdling shriek of 10,000 fans stretch[ing] from 157th Street to 140th Street, thousands and thousands of them.” [source]

At left: Photo from the Evening World, 10/11/12

Precisely at noon, the commission, located at the Waldorf-Astoria, telephoned to announce that the baseball game could be played, and the throng thundered into the stadium. The Evening World compared it to the Spanish running of the bulls. “[N]o man of this generation ever saw such racing and pounding along the sloping approaches of the Polo Grounds and began slamming down seats at one minute past twelve o’clock today.”

According to New York Post columnist Mike Vaccaro in his book on the 1912 World Series ‘The First Fall Classic’, the stadium filled to capacity with thousands more watching from various nooks and crannies, over 40,000 people, “officially…the third largest in this history of this stadium (and, thus, the history of the sport) but unofficially shattered that record to smithereens.” Many thousands more listened in to an announcer in Herald Square.

And so, here’s the punchline: after all that madness, the New York Giants lost the game, on the muddy and thoroughly distressed Polo Grounds, to the Boston Red Sox, 3-2! The New York Times intoned, “Nine Grim Innings To Red Sox Victory.”

In fact, they went on to lose the entire series to Red Sox.

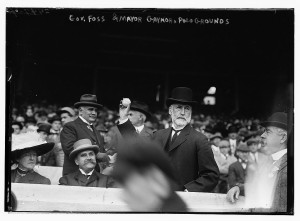

Below: For Game One, Mayor William Jay Gaynor threw out the first pitch, sitting alongside the mustachioed Massachusetts governor Eugene Foss. Less than a year later, Gaynor would succumb to injuries brought on by a bullet lodged in his throat, the unlucky souvenir of an 1910 assassination attempt. [Read more about Gaynor here.]