Trauma in Times Square: An electrical sign destroyed by the massive windstorm of February 22, 1912. One Times Square sits to the left, and the Hotel Astor is in the distance. [LOC] Shorpy has an another angle of this damaged storefront.

“The great gale that blew in with Washington’s birthday will not soon be forgotten. It was the biggest New York ever knew.” — New York Evening World, Feb. 23, 1912

On February 22, 1912, a catastrophic weather anomaly occurred in New York City, an event the New York Times referred to as ‘The Big Wind’.

This particular day has also been called “a significant day in the history of tall buildings,” although I doubt anybody today will be celebrating this rather vicious and sudden test of architectural endurance.

New Yorkers thought it might be worse. The storm system began the previous day as a blinding Midwestern blizzard, paralyzing the railroad and killing cattle. St. Louis received its greatest snowfall ever up to that time from this churning storm, and Chicago reported winds of up to 50 miles per hour.

If it held this pattern by the time it hit the East, New Yorkers feared another storm of the level of the Blizzard of 1888, which buried the city in snow, rendered transportation useless, and killed more than 200 people.

In one respect, the city was fortunate that snowfall was relegated to upstate New York. The grim meteorological trade off, unfortunately, was a day of powerful, otherworldly wind gusts, almost double the strength of those during the infamous 1888 storm.

The worst of it came after midnight, when a terrifying frozen bluster “swooped down on the city with all its length and breadth” at speeds of 96 miles per hour.

At one point, devices in Central Park registered an unthinkable 110 miles per hour. By morning it had settled to 70 miles per hour and held that speed steady for much of the day. [source]

Some called this “giant among gales” a day-long cyclone, and it certainly acted like one — uprooting trees, destroying rooftops and even depositing whole houses into the river. People were blown off their feet, carts went flying and pedestrians dodged falling telephone poles in terror.

Most leaving home wearing hats ran back inside without them. If any of those women from yesterday’s Astor Place post were trekking through the plaza with their home-work today, they most likely lost it to the wind.

Foremost on the minds of most New Yorkers was the fate of its skyline. In 1888, during the last harsh storm, there were no skyscrapers. In 1912, there were several over 30 floors, including the city’s tallest, the 50-floor Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower off Madison Square.

Although most buildings were designed to withstand significant wind trauma, none of them were prepared for winds above 70 miles per hour. And the building slated to become the next tallest in New York — the Woolworth Building — was still under construction, its metal skeleton now a potential arsenal of deadly debris.

Panes of glass shattered throughout the city, but it appears most of New York’s tallest structures survived without significant damage. In fact, it was the shorter, older structures that fared worst, many of them designed with little protection from powerful winds.

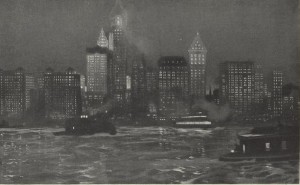

Below: the downtown Manhattan skyline in 1912. Most of these buildings survived the ‘Big Wind’ with only damage to their windows. [pic]

Not that modern invention came away unscathed that day. The electrical signs of Times Square, many no more than a few months old, were no match for the powerful gusts. Several were destroyed, including a one provocative sign at 47th Street, featuring “two scantily clad electric boys who box nightly in Summer underwear.” [source]

Next to the Hotel Knickerbocker, a 200-foot electric sign crumbled to the sidewalk below in front of Hepners Hair Emporium, a police officer racing into the establishment a minute before the sign crashed into the plate glass window of the railroad ticket office next door.

Across the street, at the Times Building, a drug store window exploded, and “many bottles of perfume and drugs” were hurled at passers-by.

Most boats all along the waterfront were either damaged or untethered. Predictably, beach houses on Rockaway Beach and other quieter locales fared the worst. The luckiest structures survived with nary a window remaining; those less fortunate were found floating offshore. In Astoria, Queens, the roof to the jail was taken off, to the fright of the occupants inside.

At right: Times Square in August 1912. The White Rock sign was probably not around for the February wind storm. The ‘electric boys’ sign described above sat at this intersection.

In Red Hook, Brooklyn, turbulent winds kept a raging fire alive at a brick manufacturing plant, distributing flaming pitch shrapnel to several buildings across the street, including a hay and horse feed dealership! (One of many reasons they don’t keep hay dealerships in crowded cities today.) The brick factory, which took several hours to control, was about three blocks from the location of today’s IKEA store.

February 22, 1912, happened to be the 180th anniversary of George Washington‘s birth, and hundreds of veterans tried marching from Jefferson Market to Union Square. Flags raised aloft in celebration were torn to ribbons. Nobody was injured, although the gusts caused major inconvenience, “Salvation Army object lessons and banner bearers bowled over by the wind.” [source]

Others were not as fortunate. The Times attributed at least one death to the storm and over a dozen concussions from flying debris, messenger boys and seamstresses blown into windows or railings or hit by signs or dislodged cornices.

One man, waiting for his wife at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, had his neck slashed by flying glass. Where physical harm was avoided, humiliation took its place. A society woman on Riverside Drive, wearing “superabundantly costly furs,” was picked up and thrown into a horse.

Meanwhile, down at the Battery, Frank Coffyn was preparing for another takeoff off the water on his pontoon-equipped airplane. The wind had other plans, ripping the wings off the plane and spoiling Coffyn’s flight. Later that day, Coffyn wired his old boss Wilbur Wright for replacement parts. (See my previous post for more information of Coffyn’s harbor flights..)

By the late evening, winds had died down to a mere 44 miles per hour. (For comparison, New York City’s average wind speed today is just 12.2 miles per hour.) In the morning, things were back to normal — except for huge mess of metal and glass left scattered on the streets.

1 reply on “The Big Wind of 1912: New York skyscrapers in peril, as monster gales hurl “men and women down city streets””

Love reading about the past and what was the original makings and now are different from when they were first built. Like the limelight building ? My old club the 80’s where the best!