Mr. Seward, with the best seat in the park in 1934. He does seem awfully thin though, almost like a certain president. (At least, some people thought so.)

This month marks the 135th anniversary of an extraordinary gift endowed to Madison Square Park — the statue of William Seward. the former New York governor and Secretary of State under Abraham Lincoln. Indeed, he’s easily one of the most influential New York politicians ever upon the national stage. A master of backroom politics and a proponent of American expansion (best known for negotiationg the purchase of Alaska from the Russians in 1867), Seward died a revered figure, and monuments to his legacy sprouted up throughout the nation, from shore to shore.

In New York City, there are two key landmarks named after him, and they could not be more different.

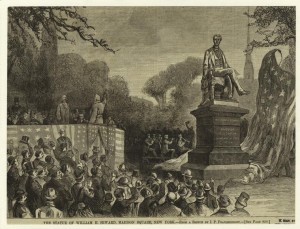

The aforementioned bronze statue at the southwest corner of Madison Square Park was presented with the maximum of pomp and circumstance in September of 1876. The work, by Randolph Rogers, depicts Seward in a seated, almost languid pose, with unusual proportions. As has been frequently speculated, Rogers might have adapted an earlier seated statue of his, depicting Abraham Lincoln, and simply slapped Seward’s head onto it. This is unproven, of course, but since Lincoln was Seward’s old boss, it makes for amusing symmetry.

But the gathering admirers on the afternoon of its unveiling scarcely seemed to notice. Present at its debut was future U.S. president Chester A. Arthur, who would be graced with his own statue in Madison Square Park 23 years later.

Further downtown, in the Lower East Side, at the convergence of Essex Street, Canal Street and East Broadway, lies Seward Park, also named for the venerated politician. In 1897, in a neighborhood desperate for breathing room, the city condemned a cluster of tenements lining the east side of Essex Street. The fenced-in park was pretty much developed by private groups until the city intervened in 1903, equipping the grounds with a sporting pavilion and leveling areas for a playground.

But the real jewel of this park came in 1909 when the Carnegie Foundation placed one of its most stunning libraries here. By the way, Jefferson Street used to separate the library from the park (as evidenced in the picture above). Today, the road has been closed off and the space has been become part of the park itself.

So the development of this park came well after Seward (or the head of Seward, on Lincoln) was placed uptown. And really, they weren’t going to place so a lavish memorial in the midst of so many tenements, were they?

However, Seward himself might have considered Seward Park the far greater honor. During his years as governor (1839-42) and many years following as a New York senator, he supported many pro-immigration policies that were considered extraordinarily progressive for the day. Naming the park after him was a tip-of-the-hat to these early risky political stances.

Pictures courtesy NYPL. (link to top photo here)