Continuing with the theme of ‘1864’, here’s a revised and expanded version of an article I wrote back in 2009 on the man who was mayor of New York during that crazy year:

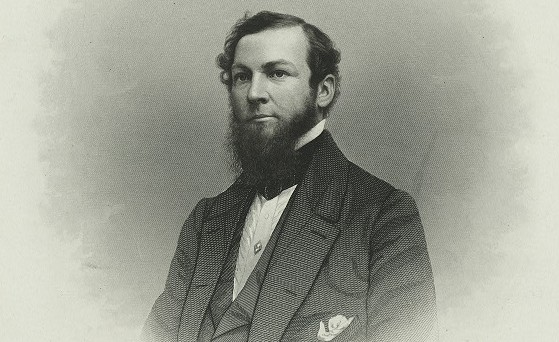

KNOW YOUR MAYORS Our modest little series about some of the greatest, notorious, most important, even most useless, mayors of New York City. Other entrants in our mayoral survey can be found here.Mayor C. Godfrey Gunther

In office: 1864-1865

His past glories were built on a mountain of fur pelts, and his future would wash up on the half-developed shores of Coney Island. But in 1961, it was Civil War that nearly derailed the political career of Charles Godfrey Gunther.

The groundwork was laid in 1857 by former mayor Fernando Wood, who rebelled against Tammany Hall, the Democratic machine he formerly led, to form his new political organization called Mozart Hall. This assemblage of working class reformers and Wood devotees returned him to City Hall in 1960, foisting from office the German paint mogul Daniel Tiemann who had first unseated Wood back in 1857.

Back in business, Wood heralded a feisty pro-South, anti-abolitionist stance, pitting himself against Albany and threatening to secede Manhattan from the state.

By the election of 1861 however, a swell of national support for the Union cause turned against Wood. The Democrats were in a precarious spot, splintered between rival Democratic groups. It’s here in our story where we introduce Charles Godfrey Gunther, Tammany’s official candidate for mayor in 1861.

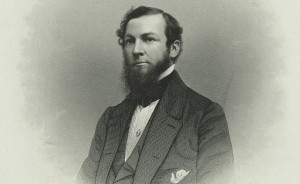

Gunther was born at Maiden Lane and Liberty Street, on Feb 7, 1822 — into a German family that had made its fortunes in the fur trade, rivals of the city’s true fur king, John Jacob Astor. Charles spent his youth in his father Christian’s tutelage, taking over the family mercantile business C.G. Gunther & Co. (pictured at left)

Charles was active in Democratic politics at an early age, sharpening his teeth during party squabbles. In 1855, he was elected an almshouse governor, overseeing the city’s prison and pauper populations. (The blog Correction History has a nice rundown of this unusual elected job function.)

His backroom political successes, paired with his wealth, attracted the attentions of Tammany Hall. The furrier’s son worked his way up through the political lodge, eventually becoming sachem (or district leader) in 1856.

He was Tammany’s candidate for mayor in 1861, against the rebellious Wood, and it would have made for a fine contest between them. Wood still had his Irish supporters, but Gunther’s inclusion lured German voters away from him. In fact, Gunther did beat Wood in that election, scoring 600 more votes than Wood.

But of course, there was another contestant, the Republican George Opdyke. With Wood and Gunther appealing to the same constituencies, they split the traditional Democratic vote, and Opdyke ascended to office.

Perhaps Charles should have been grateful. The years 1862 and 1863 were not gracious times to be mayor of a major city. Opdyke’s execution of military conscription angered poorer New Yorkers, and his fumbled handling of the ensuing draft riots permanently damaged his political reputation.

By the fall of 1863, New Yorkers craving a change in leadership were given a strange buffet of choices. The Republicans, shedding Opdyke and at a serious political disadvantage, brought forth alderman and gun-maker Orison Blunt, inventor of the ‘pepper box gun’. Tammany meanwhile offered up Francis I. A. Boole, a rather corrupt city official notable for heading the street cleaning department.

With these weak choices at such a pivotal period in history, rebels from both parties — and heavily peopled with disenfranchised former Wood supporters — split to form a temporary coalition of working class Irish and Germans.

With these weak choices at such a pivotal period in history, rebels from both parties — and heavily peopled with disenfranchised former Wood supporters — split to form a temporary coalition of working class Irish and Germans.

With the strong support of the city’s surging German newspapers, Gunther was chosen as their candidate. That November he swept past Blunt and Boole to become New York’s 77th mayor. Boole took it especially hard; he “became insane and died shortly afterwards.”

Was the Gunther an effective mayor in 1864? His reviews have always been mixed. An “honest, pleasant gentleman, with frank and cordial manners,” he’s praised for his penny pinching tactics, at one time even cancelling a celebration of George Washington’s birthday as it was thought to be too extravagant. In 1964, on the verge of a national election, he clamped down on any serious city celebrations of Union victory as being too ‘political’ in nature.

Many, however, saw a darker reason for Gunther’s actions. He was also pro-South and anti-war, but practically so and far less treasonous sounding than Wood. “He was probably a genuine pacifist,” according to author Ernest McKay. “His opposition was a matter of principle that appeared to be closely connected with his religious beliefs.” Let’s just say, I doubt either Fernando or Benjamin Wood considered Gunther much of a political ally.

Regardless, throughout his term, Gunther attempted to curtail renewed draft efforts in the city and tried to deter ‘brokers’ from hanging around Castle Garden and signing up green young men from off the immigrant boats. He made public strides to prevent a potential anniversary of the Draft Riots, although it is unclear whether such violence would have reoccurred in 1864, with the war clearly gaining steam for the Union.

The new mayor also strived to clear the streets during his tenure, with the removal of slaughterhouses and roaming herds of cattle all over the city.

Ultimately, Gunther was seen as a rather weak political figure, with little influence over other city offices. Perhaps this was because he was comparatively honest — living “by his principles” according to McKay — and the bureaucracies of city government dreadfully corrupted. Running for re-election in 1865, he was crushed in the polling, with three other candidates out voting him. The victor that year was true-blue Boss Tweed crony John Hoffman.

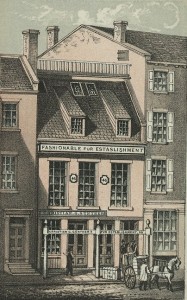

Above: the Coney Island terminal for the Brooklyn, Bath and Coney Island Railroad line

Gunther’s story doesn’t end here. He became a prominent leader in New York volunteer fire department and eventually even a partner in a very lucrative venture — the Brooklyn, Bath and Coney Island Railroad. It was this rail line that allowed thousands of New Yorkers to escape the city, eventually transforming Coney Island into a popular resort and amusement palace.

The train line, nicknamed Gunther’s Road, operated “six steam locomotives and 28 passenger cars” and “carried almost 400,000 passengers” in 1882 alone. Gunther would even own his own resort out on Coney Island, although it burned down a few years later.

And I end with a rather colorful anecdote from a 1906 article about Mr. Gunther and his railroad, from The Third Rail:

“There was one engineer who had served in the war of the rebellion, and who was particularly patriotic, who painted his engine red, white and blue.

Gunther saw it from a distance, on its first trip, tearing across the country, and he was frantic.

“For God’s sake, Drummond,” he said, when he overtook his engineer, “whatever possessed you to paint that engine red, white and blue?’

“You’re a true American, ain’t you?” said Drummond.

“Yes, but-but-“

“Well, so am I.”

“Yes, but that engine looks like a traveling barber shop.”

Gunther could not convince Drummond, however, and the latter quit his job rather than submit to any alterations.

The engine was afterwards painted according to Mr. Gunther’s ideas.

It was painted a flaring yellow.”

Mr. Gunther died on January 22, 1885 and is buried at Green-Wood Cemetery.

ADDED: One of our Facebook fans reminded me of an even more spectacular fact about Mr. Gunther — there was actually a short-lived Brooklyn neighborhood named after him. Guntherville was actually part of the pre-consolidation town of Gravesend and naturally featured many properties owned by C. Godfrey. The map below from 1873 illustrates its place along the Gravesend shore. Judging from comparing maps, it appears that part of Guntherville would later comprise the fleeting, beach side amusement venture Ulmer Park.

Pics courtesy of the New York Public Library