Just a barrel of laughs: Prohibition agents dump illegal containers of wine into the streets.

FRIDAY NIGHT FEVER To get you in the mood for the weekend, on occasional Fridays we’ll be featuring an historic New York nightlife haunt, from the dance halls of the old Bowery, to the massive warehouse clubs of the mid-1990s. Past entries can be found here.

LOCATION: The Bridge Whist Club

44th Street between Madison and Fifth avenues, Manhattan

In operation: 1925-1926

Prohibition in the United States didn’t extinguish the taste for liquor. The Eighteenth Amendment, ratified in 1919, outlawing the sale and transportation of alcohol, merely inspired those who sold it to become more creative.

In New York, prohibition even redefined midtown. Where once nightlife gathered around supper clubs and cabarets in major plazas like Times Square and Columbus Circle, speakeasies now slithered down the side streets and into previously unremarkable buildings. Some of the most famous of these illicit 1920s booze joints were housed in old tenements and small storefronts, down numbered streets off of Times Square and further downtown in Greenwich Village.

Outside the spotlight, a new regime of proprietors, building newfound nightlife empires with mob ties, quenched the thirsts of a populace thirsty for that which they weren’t legally allowed to partake. A great many vied for this business, with a reported “30,000 to 100,000 speakeasy clubs” formed by 1925.

That is an absurd number, reflecting the diversity in establishments — from the gentlemen’s clubs behind secret doors and the high-kicking lounges owned by Larry Fay and Texas Guinan to rundown tenements hastily fashioned with a bar and a few bottles. With no liquor sold there were no liquor licenses required. Everybody could get in the game.

How could the federal government even try and combat such widespread and diverse abuses of a virtually unenforceable law? One tactic manifested in 1925 when, in certainly one of the strangest undercover operation in the history of U.S. law enforcement, the feds got into the speakeasy business themselves. If you can’t beat ’em, drink up and join them.

In the fall of 1925, the United States Bureau of Prohibition sunk a few thousand dollars ($5,576.50, according to official documentation, almost $70,000 today)

to rent a building at 14 East 44th Street to construct its own speakeasy, called the Bridge Whist Club. The dive, called a “plush booze joint” by Herbert Asbury in his history of the Prohibition years, was named for a card game, and it is likely men gathered there to partake in this diversion.

But most were there for the liquor. The undercover agents, meanwhile, used the joint to gather “information concerning the activity of liquor smugglers.” Rubbing elbows with drinkers, agents could theoretically get names of other speakeasies and establish connections to leaders in New York’s underworld. Tables were even equipped with recording devices to pick up incriminating details.

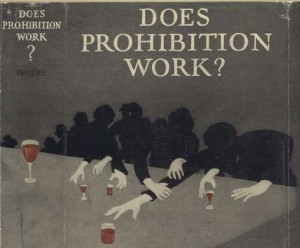

Below: From the jacket of a 1926 book by author Martha Bensley Bruere (courtesy NYPL)

In essence, they were feeding the small fish to draw out the larger ones. The Treasury Department, tasked with enforcing Prohibition by 1925, was well aware of the shifty nature of the enterprise. But an ethical distortion in the philosophy of the Bridge Whist actually put its patrons at risk.

As Wayne Wheeler, head of the Anti-Saloon League, put it, “The government is under no obligation to furnish people with alcohol that is drinkable when the Constitution prohibits it.” So the Bridge Whist served up a mixture containing wood alcohol, also known as Methanol, linked today with causing blindness.

This is not the first time that the U.S. government introduced dangerous substances into illegal drink. Realizing that many bootleggers stole industrial alcohol to make their product, enforcers directed that the industrial stuff be polluted with Methanol, hoping the foul taste and physical illnesses would deter consumption. (Slate Magazine ran an eye-opening article about this last year.)

Some of this toxic mix was sold at the Bridge Whist; other batches infiltrated through speakeasies throughout New York. According to author Deborah Blum, “In 1926, in New York City, 1,200 were sickened by poisonous alcohol; 400 died. The following year, deaths climbed to 700.”

Still, the Bureau claimed such tainted booze was “the most effective denaturant which the government could use, since it was the most difficult denaturant to remove” by bootleggers with their own chemists, tasked with cleaning up the toxic stew.

Having the government in the speakeasy business did not settle well with many in Congress. Anti-Prohibition members equated it to entrapment. Indeed, many arrested due to information gleaned from the Bridge Whist were later set free. Only one “mid-level bootlegger” was ever caught from information gleaned from the speakeasy operation.

New York congressmen Fiorello LaGuardia, ardently against Prohibition, petitioned against the use of ‘under-cover funds’ and extreme measures of enforcement. Ultimately, the Bridge Whist could not weather the scrutiny, and thanks to the efforts of the future mayor of New York, the experiment was officially shut down in May 1926.

1 reply on “Bridge Whist Club: The worst booze your taxes can buy!”

Was there also a club called Whist Club in New York? I have a bridge set with a card in it that is dated Nov 1 1932, which has an Auction Bridge Table of Points revised in 1926. It is a 2 sided card with some rules on it, that came with the set. It is printed by special permission of the Whist Club (New York) Edited by Milton C. Work. thanks,