The Villard Houses, a Madison Avenue masterpiece by the firm McKim, Mead and White, was mostly the inspiration of their associate Joseph Wells, according to the author. [courtesy NYPL]

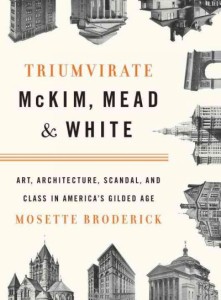

Triumvirate: McKim Mead & White

Art, Architecture, Scandal, and Class In America’s Gilded Age

by Mosette Broderick

Alfred A. Knopf, New York, Publisher

BOOK REVIEW I’ve been going back and forth for a couple weeks about whether to recommend Mosette Broderick’s ‘Triumvirate: McKim, Mead & White: Art, Architecture, Scandal, and Class in America’s Gilded Age’, the indulgent and labyrinthine story of the legendary New York architecture firm, in many ways a book that’s as cluttered, over scaled and ornate as any Beaux-Arts building. And, for that reason, at root a fine way to tackle the material.

McKim, Mead and White is largely responsible for the most romantic of New York’s great structures, the premier creators of landmarks, towers and townhouses in the late 19th century, distilling centuries of architectural technique and flourish for the purposes of turning America into an outsized version of Europe. But their tale has always been lopsidedly told, thanks in part to Stanford White’s flamboyant personality and his scandalous murder atop Madison Square Garden, a building he himself designed.

Broderick, a New York University professor of art history, doesn’t quite recalibrate their story to its logical center, but she comes close. ‘Triumvirate’ is an exhaustive tale of opulence and wealth in the Gilded Age, with a literal cast of hundreds, recounted with a modern reverence to high society.

Curiously, the three men whose names would become synonymous with great American architecture and decoration came neither from great wealth nor fine society. Charles McKim grew up in an ardent abolitionist household and married himself into money, only to become a widower early on and withdraw from social interaction. Stanford White achieved what his social-climbing father could not, fostering a circle of creative friends (and possibly lovers) and ascending into high fashion by strength of will.

Their proximity to society is crucial, one of Broderick’s central points. They built upon family connections, friendships at social clubs and a glowing reputation garnered from commissions in summer locales like Newport, RI. The book immerses you into the social architecture that would lift the firm’s reputation.

The third member of the ‘triumvirate’ William Rutherford Mead, more manager than architect, is a passive presence in this story. Instead Broderick focuses on some of the other men at the firm, most notably the talented Joseph Wells, depicted here almost as a romantic archetype, a creative inspiration for Stanford White and possibly more.

The third member of the ‘triumvirate’ William Rutherford Mead, more manager than architect, is a passive presence in this story. Instead Broderick focuses on some of the other men at the firm, most notably the talented Joseph Wells, depicted here almost as a romantic archetype, a creative inspiration for Stanford White and possibly more.

The firm’s early projects (both great and small), their forgotten masterpieces and their greatest enduring successes are all catalogued here with a glowing sense of detail, lines of influence of drawn between them. For instance, an extraordinary flourish from a tony New York townhouse might have first appeared on small Newport summer home commission a few years earlier. Broderick applauds their penchant for imitation and their creativity to combine architectural components.

The book is at its most effective when talking about icons — places like the Villiard Houses, the Washington Square arch, the Columbia University campus, and the especially Pennsylvania Station. (“The station’s destruction helped to spark the creation of the Landmark Preservation Commission, but one wishes that a less significant building had to be sacrified to this end.”)

I don’t have a deep background in architecture but I was riveted to many of her descriptions of various office buildings and mansions, places I had never heard of and were long demolished. And the discussion is not just of exteriors; Broderick goes out of her way to establish White as an expert interior designer and furniture hunter whose treasures populate local museums to this day.

Props to the team at Knopf for gathering some remarkable photographs, many nestled within the text itself.

The pictures are greatly needed at times. The story is layered (and layered and then layered again) with the minutiae of New York social affairs, with so many proverbial bold-faced names that had they really been bold faced, the printer would have ran out of ink. She sets the story into context only too well, so much context that it often obscures the point. There are a great many tangents of interest, most notably that of department store mogul A.T. Stewart and the fate of his estate, but most often overstay their welcome.

Broderick’s depiction of White’s alleged homosexual proclivities is interesting. She addresses it almost immediately, then says “the sexual orientation of White and the circle he favored is of no important to the work he did and is best left in simple form here.” But far from leaving it, the narrative peers at it and speculates at any given chance. White’s relationships with Wells, Augustus Saint-Gaudens and others can only be inferred. And Broderick, she infers, on this and on some of the salicious events in McKim’s first marriage. Okay, I’ll admit, it makes for a juicier read.

Combined with the book’s social-calendar aspect, ‘Triumvirate’ can feel like a gossipy novel woven into a serious dissertation on Gilded Age architecture, a combination that is so strange — expressing itself in elegantly structured prose one moment, and dry, old-fashioned text the next — that at the end of the day, I cautiously recommend this.

The book’s flaws only prop up the material, and once you settle into the unusual rhythms, you may find yourself planning a McKim, Mead and White house hunting trip in the near future. Broderick gives you tools, as long as you peel away the doilies.