In 1906, visitors to the Bronx Zoo observed a rather bizarre sight in the Monkey House — the exhibition of a man in African dress, often accompanied by a parrot or an orangutan.

An African pygmy, so read the sign, “Age, 23, Height, 4 feet 11 inches, Weight 103 pounds, Brought from the Kasai River, Congo Free State, South Central Africa.” Displayed in one of America’s foremost institutions devoted to the display and care of exotic animals. Elephants, tigers, polar bears, snow leopards, bison. And one young man named Ota Benga.

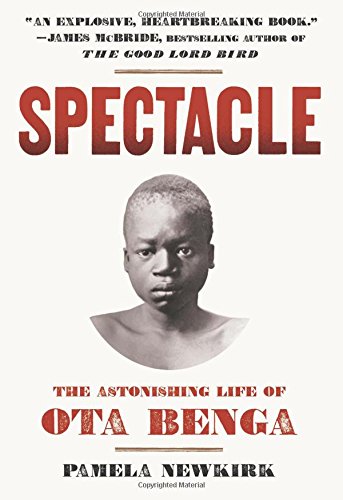

He is the subject of Pamela Newkirk’s engaging new book Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga, both a sincere ode to his tragic life and a contemporary accusation of the terrible forces that exploited him over a century ago.

But the story is really about the ghost of Ota Benga.

He spoke little English and there are no accounts from his perspective. Almost everything we know is from the perspective of a jaundiced press and the glare of condescending authority. He was the subject of great fabrications over the years; the truth is almost impossible to extricate from hyperbole.

While his story is front and center in Spectacle, but he barely raises his voice. He never had one.

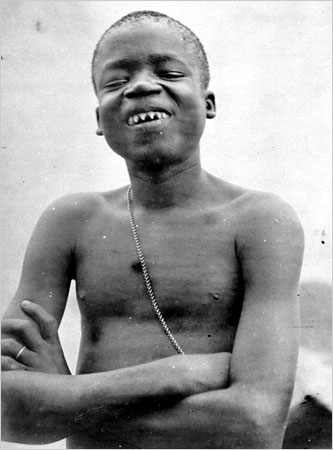

![1906 photograph of Ota Benga, described as being taken at Bronx Zoo. (Wikimedia) Title: Ota Bengi Creator(s): Bain News Service, publisher Date Created/Published: [no date recorded on caption card] Medium: 1 negative : glass ; 5 x 7 in. or smaller. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ggbain-22741 (digital file from original negative) Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. Call Number: LC-B2- 3971-2 [P&P] Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print Notes: Title from unverified data provided by the Bain News Service on the negatives or caption cards. Forms part of: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress). General information about the Bain Collection is available at http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.ggbain Format: Glass negatives. Collections: Bain Collection Bookmark This Record: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ggb2005022751/](https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/tumblr_mblqmjIlfr1rxtv35.jpg)

Creator(s): Bain News Service, publisherÂ

This is probably true although Verner is an unreliable source, often changing his own biography to burnish his reputation in the science community.  Verner was the product of his age, seeing Africans as inferior beings but seeing their continent as a source of revenue. Verner sought to profit handsomely from his ‘explorations’ both by currying favor with the Belgian King Leopold II (the ruthless leader who exploited the people of the Congo) and by snatching human specimens for display in America.

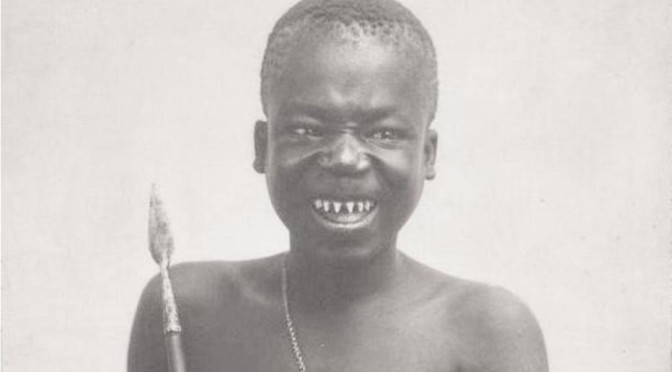

Ota Benga first arrived with a group of other men and boys for an exhibition at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. Â People delighted at his mischievous nature and unusual appearance. His teeth were filed into points, a decorative trait that exhibitors (including Verner) proclaimed were the product of a cannibalistic nature.

Below: Ota Benga at the St. Louis World’s Fair with other men taken from AfricaÂ

He went back with Verner to Africa only to arrive back in America by 1906 where he was placed in the care of the American Museum of Natural History. Ota Benga actually lived inside the museum, subject to more than a few indignities. “I have bought a duck suit for the Pigmy,” wrote Hermon Carey Bumpus, the director of the museum, to Verner. “He is around the museum, apparently perfectly happy and more or less a favorite of the men.”

Ota Benga’s removal to the Bronx Zoo and subsequent display in the Monkey House has certainly been a blight to that institution’s history. The decision reveals the outmoded and racist philosophies that pervaded scientific thinking of the day.

At best, Ota Benga was simply an object in an exotic diorama with audiences prodding him to do tricks. His humanity was barely considered. At worst, the exhibition lays bare the racism of the day in the most baldy sinister way possible, corroding even the most esteemed institutions of the day.

It’s a small relief to hear of the many criticisms the zoo received in the press back in 1906. Sanity soon prevailed and Ota Benga left the zoo to live in an orphanage in Weeksville, Brooklyn.

Newkirk gives the life of Ota Benga a proper eulogy. She crafts an intriguing tale around the many uncertainties of his biography, sometimes even stopping to analyze his state of mind.  I greatly credit the author for parsing through volumes of inaccurate news reports in search of even the smallest grains of truth.

Newkirk gives the life of Ota Benga a proper eulogy. She crafts an intriguing tale around the many uncertainties of his biography, sometimes even stopping to analyze his state of mind.  I greatly credit the author for parsing through volumes of inaccurate news reports in search of even the smallest grains of truth.

His story ends with an unsatisfying hollowness, outside New York and far from the Congo. Few in his life ever treated him as an equal. In fact, due to his size, he was frequently treated like a boy, although he mostly like ended his life in his early 30s.  He never found a place to fit in.

There’s only a single moment in the book where Newkirk lets us in on his marvelous potential, on a life that could have been under more fair and enlightened circumstances.

He becomes, for a moment, “a father figure and hero” to a group of small African-American boys in Lynchburg, Virginia. Â “In Benga they found an open and patient teacher, a beloved companion, and a remarkably agile athlete who sprinted and leaped over logs like a boy. And with his young companions Benga could uninhibitedly relive memories of a lost and longed-for life and retreat to woods that recalled home.”

Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga

Amistad, HarperCollinsPublishers

by Pamela Newkirk

Other recently reviewed books on the Bowery Boys Bookshelf:

2 replies on “‘Spectacle’: The Story of Ota Benga”

When the museum director mentions that Ota Benga had a ‘duck suit’, I think he meant a suit made of duck canvas material, not a suit that looked like a duck. It makes this story only a tiny bit less weird and disturbing.

His being in the monkey cage spearheaded, if you will, the birth of the NYCHA Project concept.

Nothing weird or disturbing at all.