In the early days of July 1915, the United States was preparing for a subdued celebration of America’s 139th Independence Day.

It was hardly a festive time. War was still raging in Europe, and America was debating its entry on the side of Britain, Italy and France.

The deaths of 128 Americans aboard the RMS Lusitania on May 7 had forced the U.S.’s hand, some thought. President Woodrow Wilson pressed Germany for an apology while not yet calling for war. His Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan thought even that too harsh; he resigned in protest from Wilson’s cabinet in June.

The headlines were dire as it seemed the entire world would soon be caught in the maelstrom of the Great War.

And then, right before midnight, July 2, 1915, a bomb went off at the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, D.C.

It exploded in an empty reception area. “The explosion was a loud one and shook the entire building, breaking transoms and shattering plastering, ” said the Sun. Windows and mirrors were smashed, but the only bodily harm it caused was throwing a watchman from his chair.

The Sun: “Some persons in the crowd which had gathered around the Capitol were inclined to believe that the bomb had been placed by some war fanatic as an act of resentment against the United States government.”

Below: The Capitol reception room after the explosion

They were right. And Eric Muenter wasn’t done.

Before newspaper readers in New York City would find out about the bombing, its instigator would have already arrived in their city, with a roster of further crimes on his mind.

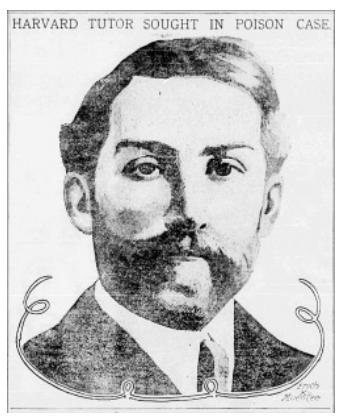

Muenter (pictured below), a former professor at Harvard University*, was a German sympathizer angered at American intervention in the war. He spread his vitriol wide, preparing to target private businessmen personally funding war efforts. In fact targeting one of America’s most wealthy financiers — JP Morgan Jr.

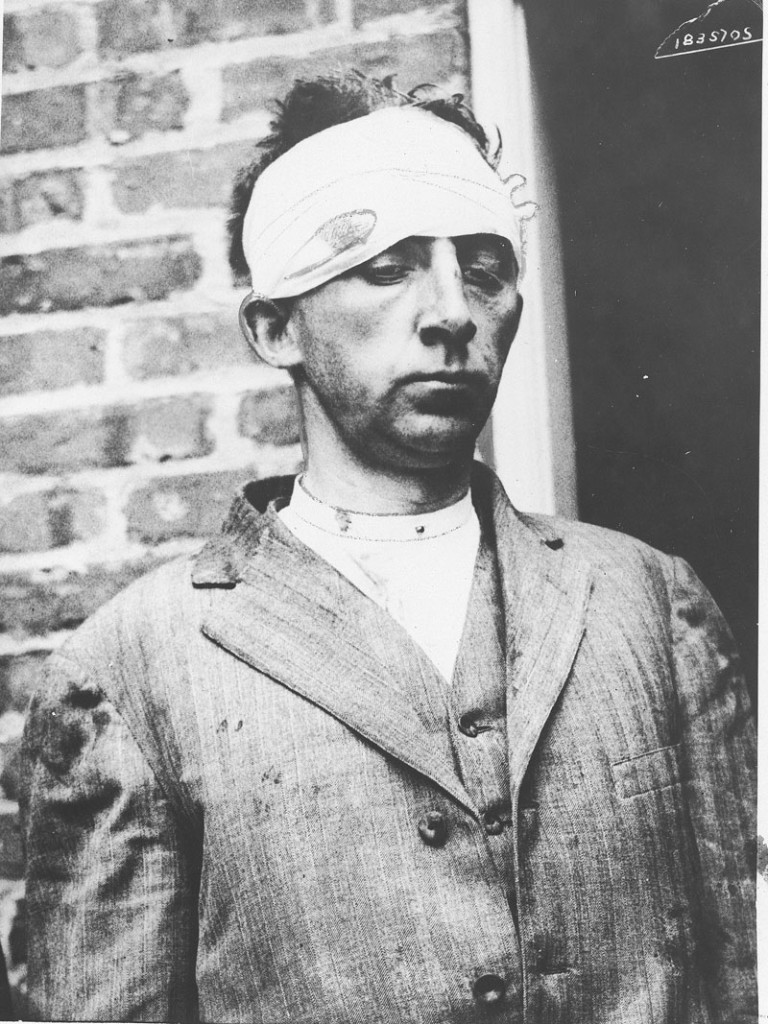

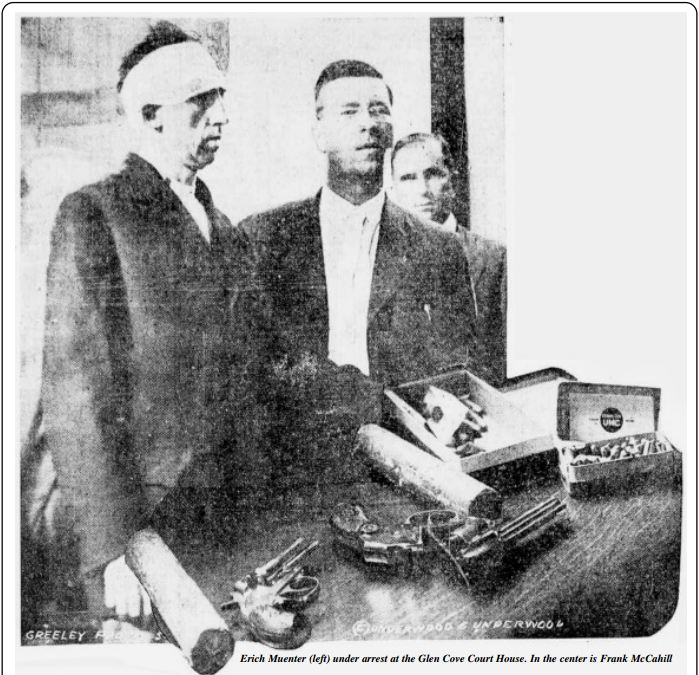

Below: Muenter after he was captured

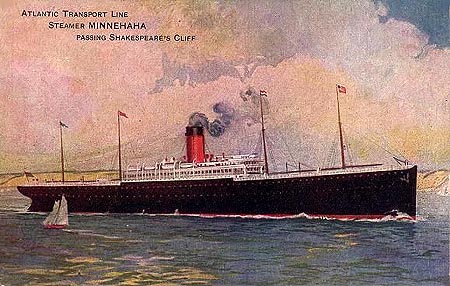

Following his sabotage at the Capitol, Muenter fled to New York on the morning of July 3 to wreak further chaos. He had a makeshift headquarters at the Mills Hotel (Seventh Avenue and 36th Street) where he had stored dozens of sticks of dynamite and fuses. At the port of New York, he managed to sneak aboard the SS Minnehana, an ocean liner filled with explosives destined for England, and install a time bomb to detonate once the ship was at sea.

It’s at this time that a similar time bomb was placed at New York Police Headquarters at 240 Centre Street. The device here was later believed to be from the same batch of dynamite as Muenter’s. If he was involved, you have to admit he was incredibly efficient with his time, for by 8 am, he had boarded a train, headed to Glen Cove, Long Island.

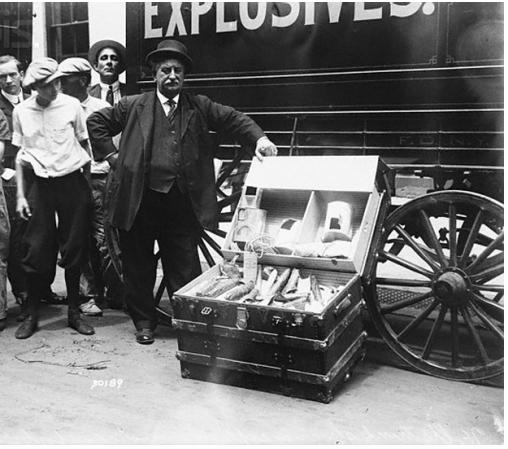

Below: New York’s Inspector of Combustibles with Muenter’s steamer trunk filled with dynamite. (Courtesy Glen Cove Heritage)

JP Morgan Jr. had been in control of his father’s banking empire since the elder’s death in 1913. The son embodied America’s involvement in the Great War in the years before the U.S.’s official entry. He facilitated an unprecedented loan of 500 million dollars to the Allied countries, backed by a consortium of over 2,000 American banks. The loans would soon grow to almost 3 billion dollars.

This made the financier both a symbol of American beneficence for some and a target of unwanted intervention for others. New York was a great stew of European diversity in the 1910s, and the far-away war often played out in the streets of New York, especially in German communities.

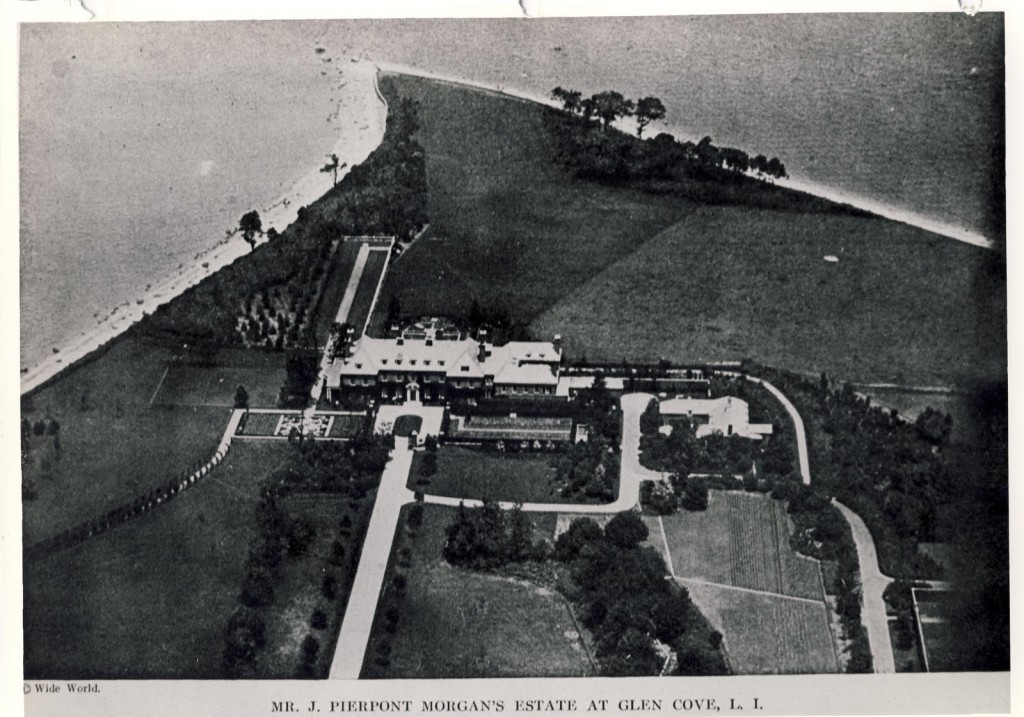

Morgan Jr had his recently-built summer home in Glen Cove, a palatial manor called Matinecock Point (pictured below). This was Muenter’s destination.

The assailant arrived, armed with two revolvers and a set of dynamite in his pocket, during an opportune breakfast meeting; the Morgans just happened to be entertaining the British ambassador Sir Cecil Spring-Rice.

At the door, Muenter pulled a gun on Morgan’s butler who, quickly thinking, directed the intruder down an opposite hall then shouted in the other direction for the Morgans to hide. The family scattered throughout the house.

Eventually, for the safety of their children, the Morgans did appear at the second floor landing and lured Muenter to them.

“Now Mr. Morgan I have got you.” he said reportedly.

His wife Jane attempted to leap in front of the gunman but was harshly shoved out of the way. Muenter then shot Morgan twice and prepared to fire again from the second pistol.

Fortunately Morgan had actually fallen into the gunman, pinning him to the floor. This allowed time for Mrs. Morgan and the children’s elderly nurse to finally apprehend the shooter. The fact that Spring-Rice, the British ambassador, also personally assisted in the capture of the shooter seems especially notable.

His plan thwarted, Muenter reportedly exclaimed, “Kill me! Kill me now! I don’t want to live any more. I have been in a perfect hell for the last six months on account of the European war.”

Originally giving his names as Frank Holt, it was soon discovered that the assailant was in fact Muenter, the former Harvard professor. In 1906, he was accused of poisoning his pregnant wife. Most likely, he did indeed kill her, for he disappeared from campus, changing his name to avoid arrest and had apparently spent years cultivating this new identity.

Once in custody on Long Island, Muenter spilled the beans. “I wanted to attract the attentions of the country to the outrages being committed by those who are sending the munitions of war to the Allies.” [source]

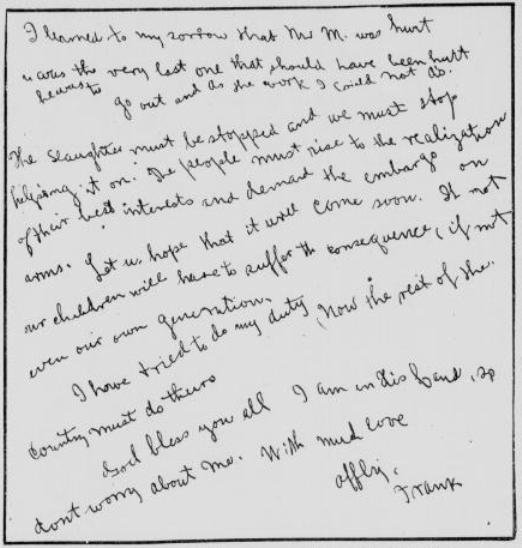

Below is a fragment of a letter Muenter wrote to his father-in-law while in custody. “I learned to my sorrow that Mrs. M[organ] was hurt,” it begins.

On July 5th the explosion at New York Police Headquarters went off, following another explosion at the home of Andrew Carnegie. Nobody was hurt in these blasts. These similar explosions were later declared unrelated to the Muenter incident itself, but it grimly reinforces the danger New Yorkers faced during wartime, even so far away from the battlefields.

Morgan quickly recovered from his injuries although the attack had a chilling effect among the residents of Long Island’s Gold Coast. Security was quickly beefed up at Matinecock Point and at the estates of other wealthy financiers associated with the Morgan bank loan.

Below: Muenter in custody

On the evening of July 6, Muenter leaped to his death from his cell at Nassau County jail in Mineola. While it was but a short drop, he had jumped head first, crushing his skull.

The death was so bizarre and sudden — it actually made a loud, deafening thud — that investigators initially believed that he had placed a blasting cap in his teeth to hasten his demise.

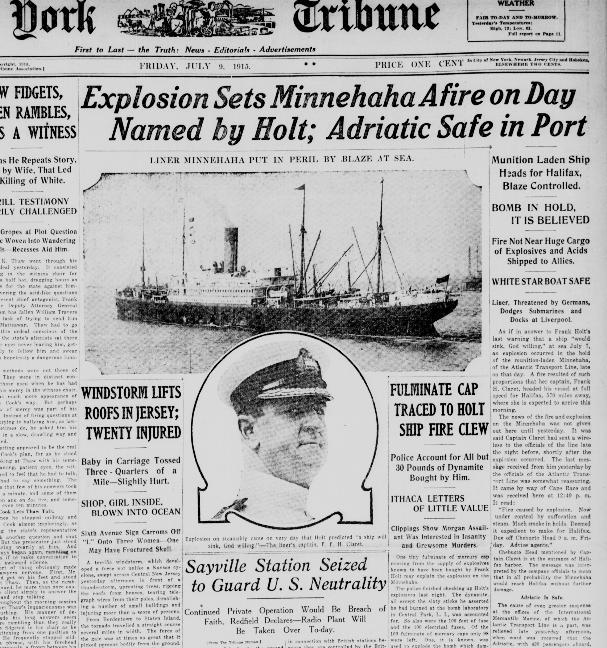

But the reign of terror wasn’t over. The time bomb that Muenter had placed aboard the SS Minnehaha did eventually explode while the ship was in the Atlantic. While it caught the ship ablaze, fortunately the ship was able to reroute to Halifax, and the fire was safely put out.

For more information on this spellbinding case, I highly recommend this excellent write-up by Daniel E. Russell for Glen Cove Heritage.

NOTE: Original version of this story featured the mugshot of another bomber Alexander Burkman. It’s been corrected to include the proper mugshot.

*Press reports initially thought he was from Cornell.

Originally published July 2 2015

3 replies on “Terror Spree: Harvard professor bombs U.S. Capitol, shoots JP Morgan”

[…] https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2015/07/terror-spree-harvard-professor-bombs-u-s-capitol-shoots-jp-… […]

The large LOC photo you have labeled as Muenter, is actually Alexander Berkman.

(fide Library of Congress source page http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3c03849/)

For Muenter, you have a couple of post-capture choices:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Eric_Muenter

Cheers!

Thank you Ellin. So weird, the other one was complete mis-labeled! I’ve put up a better one….