Right before noon on March 6, 1970, an explosion tore open a lovely Greenwich Village townhouse at 18 West 11th Street and awoke New York City to a violent new threat.

The remains of three bodies were discovered in the smoking debris but they weren’t residents of this quiet neighborhood. They were members of The Weather Underground, a radical underground unit absorbing the counter-culture spirit of the 1960s and unleashing it — oftentimes randomly and irrationally —  onto a new decade.

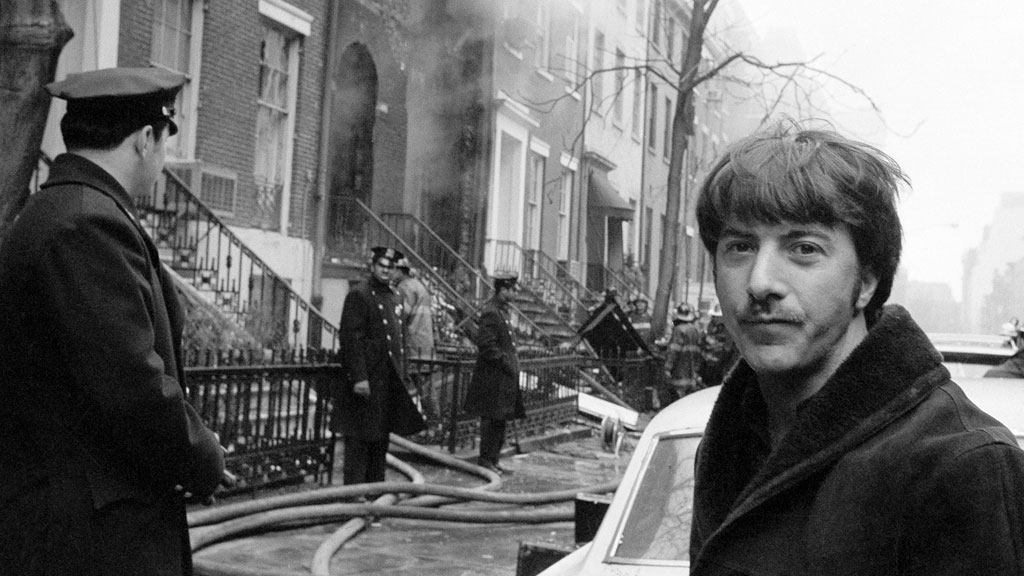

Below: Oddly enough, the townhouse explosion occurred next door to the home of Dustin Hoffman and his wife.

Less than two years later, two New York police officers were brutally assassinated in the East Village, among the most brutal and shocking crimes against the NYPD in its history.  This wasn’t a random crime but a hit placed upon the officers by members of the Black Liberation Army, wielding some of the philosophies of the Black Panthers to dangerous ends.

Almost three years later, a bomb exploded inside the historic Fraunces Tavern during in the middle of a busy weekday lunch. Four men were killed in the sudden attack, made by the Armed Forces of Puerto Rican National Liberation (or FALN).

Below: Aftermath of the explosion at Fraunces Tavern (courtesy New York Daily News)

In between these terrible disasters were several other bombings of other significant buildings, here in New York and in other cities through the United States.  All of them indicative of a violent (and ultimately failed) form of protest, as turbulently described by Bryan Burrough in his new book Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, The FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence.

This is probably one of the most frightening non-fiction books I’ve read in recent memory, a broad and exquisitely told tale that loosely links together a variety of American revolutionary action groups from the 1970s.

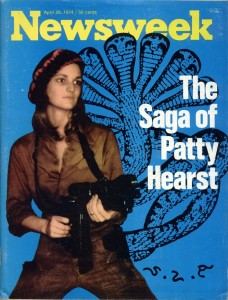

Some of the principal players of these groups are recognizable (Bill Ayers and Bernadine Dohrn,  Patty Hearst), but the breadths of their actions has been seldom studied. Through interviews with members who’ve never spoken, Burroughs patches together connections among these disparate groups — even if those connections are more philosophical than physical.

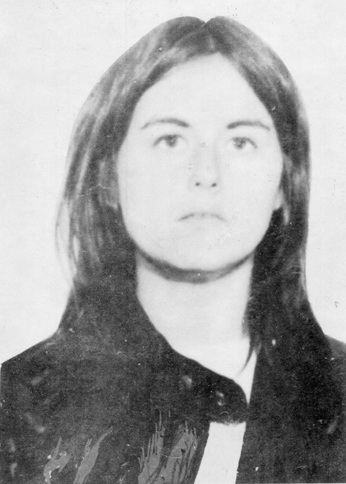

Below: The mugshot of Bernadine Dohrn, 1970

Most shared the belief that violence, disruption and chaos would lead America to a new revolutionary age. As Burrough points out, most were inspired by civil rights movement and the plight of black Americans, taking their anger and frustration into far more radical directions than the mainstream leaders who advocated non-violence and change through the law.

While the vulgar and gut-wrenching violence was often doused with machismo, many of these groups were led or operated by women.

The title comes from a series of demonstrations that occurred in Chicago in the fall of 1969, seen as a sort of kick off to this festering revolutionary movement. Â Much of the book details the ‘underground’ hideouts and escape routes of these organization, whether holed up in Manhattan’s Chinatown or San Francisco (as the Weathermen were, often dressed in silly disguises) or running from capture through rural Georgia.

Burrough does not flinch from the horror, graphically describing the aftermath of many of the more loathsome crimes. Â The 1972 deaths of two NYPD officers in the East Village is especially grim. (You can read news of the original account here.)

In particular, I found the tale of the Symbionese Liberation Army especially gripping, notable less for their violent actions (although there certainly was some) than for the somewhat random notion to kidnap the granddaughter of William Randolph Hearst.  Many of these stories will replay in your memory as a reel of black-and-white news footage or a set of iconic photographs (such as the one above of Hearst).  Days of Rage offers a vivid and refreshing new context.

Burrough — a Vanity Fair writer perhaps best known for Barbarians At The Gate — is a thorough story-teller, conjuring fully blown narratives from the sometimes untrustworthy recollections of the surviving participants.  He’s often too thorough, sometimes including superfluous details because they’ve “never before been told.”

Chaos was an organizing principal for these groups which is partially way they were ultimately unsuccessful. As shocking as some of these horrifying attacks seem today, it’s a wonder many of them were successful orchestrated at all, given the tentative organizational structure and often incompetent leadership of these groups.

Top photograph courtesy Marty Lederhandler/AP Images.

1 reply on “‘Days of Rage’ and Nights of Terror”

Terrible acts of what today would be called terrorism… yet somehow even though we didn’t enact a Patriot Act and didn’t authorize government to become Big Brother, we not only survived, but thrived and moved past the violence.

What a contrast to today – what a sad statement about society and governance in the modern world.