(For of all, I apologize, I had tons of photographs from my trip to Woodlawn that are not uploading properly. For now, I’m just using file photographs and will try and correct the problem later.)

Woodlawn Cemetary is still considered an oasis of calm and tranquility, and the dead quite enjoy it. Although a trek for most people — last stop on the 4 train, 11 stops north of Yankee Stadium — it’s still technically part of New York City, adjacent to popular Van Cortlandt Park, and only a couple stops from Lehman College. It’s a short bike ride to the Bronx Zoo.

Outside of the city’s great parks, a New Yorker rarely gets to stumble lazily over hills and hear wind rushing through trees. But the ease swiftly ceases once you realize you’ve gotten lost.

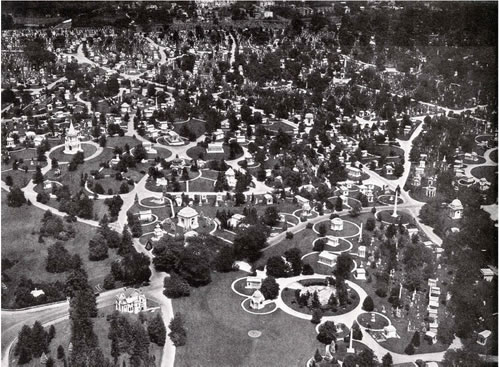

Designed in 1863 by J.C. Sidney in the same decade as Central Park, Woodlawn was created as a younger sibling to Greenwood Cemetary, a massive acreage draping Brooklyn in the ‘rural cemetary’ style, a movement advantageous with an age where New York was filled with far fewer people. Woodlawn employed some of Greenwood’s languid, relaxed nature but combined it with a far more structured landscaping, with tightly controlled plots hidden in sunken dales and around labyrinthine paths. Here’s an aerial of a last populated Woodlawn in 1921:

Woodlawn spans 400 acres of winding and confusing pathways. It is both eerie and fascinating to get lost there, which is a certainty if you go, as the map provided to you at the front gate is a fairly useless tool.

The rich and famous used Woodlawn as a way to promote their wealth after death. Some of these mausoleums, crypts and post-living mansions are bigger than Manhattan apartments and better furnished.

The resting place of Frank Woolworth, who died in 1919, celebrates the merchant as though he were a ruler of a Meditteranian empire.

William Bateman Leeds is not a name that escapes off the tongue now, but the millionaire made his money in tin, and when he died in 1909, no less than John Russell Pope (of the Jefferson Memorial in DC) designed his mausoleum. Leeds is no longer entombed there, and Woodlawn as adopted an ingenuous program for maintaining ‘abandoned’ property by selling them to new owners.

Jay Gould, industrialist robber baron extraordinaire, and his family are tucked in a Roman-style container tucked peacefully atop a hill and hidden behind a dramatic weeping beech tree.

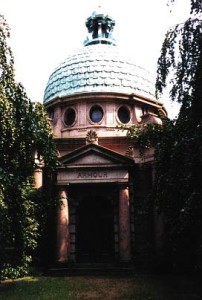

I found it curious how the bigger crypts could surround themselves with landscaping to appear ‘hidden away’, such as this one by the Herman Armour (of the meat packing mogal), designed by James Renwick, he of Roosevelt Island’s smallpox hospital and other now-creepy structures.

The landscape is strewn with examples of amazing mini-archectural examples by McKim, Mead & White (in 1885, for wall street speculator Charles Osborn), John LaFarge and Cass Gilbert while even many of the less astere have stained glass windows designed by Tiffany.

Tomorrow (if I can get my pictures to finally upload properly!) I’ll show you the resting places of legendary musicians, mayors, politicians and publishers.

1 reply on “A ghostly walk through Woodlawn (part 1)”

I ENJOY THE BEAUTY OF THE OLD MASTER ARCHITECTS AND APPRECIATE YOUR PHOTOS AND THEIR DESCRIPTIONS. I WILL BE VISITING WOODLAWN SOMETIME SOON IN THE NEAR FUTURE SINCE I LIVE IN NEW YORK,MAYBE SOME SUNDAY AFTERNOON.