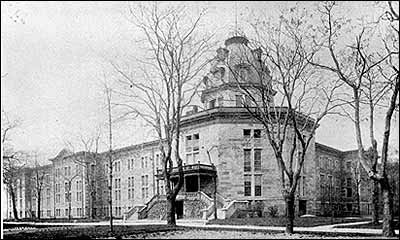

(ABOVE: Metropolitan Hospital, at the turn of the century, the former site of Blackwell Island’s asylum)

Is there anything more frightening than a insane asylum on fire? Nope.

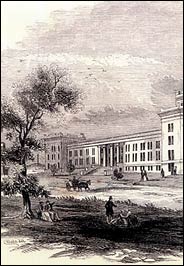

Welcome to America’s first municipal lunatic asylum, its home — you guessed it — on Roosevelt Island in the 19th century. The 1839 facility was designed by Alexander Jackson Davis, one of the most influential architects of his day and best known for decorating the northeast with austere, ornate homes. His best known New York building is Federal Hall (actually the Custom House when it was finished in 1942). The center tower of the asylum with its two L-shaped wings created an internal campus and had more in common structurally with a university or hotel.

The early 19th century was not the best time to be labelled a lunatic. The medical profession was not terribly prepared to treat mental patients; however at the time of the asylum’s construction, attitudes were shifting somewhat. As Blackwell Island, its isolation and relative calm were seen as conducive to the treatment of the mentally ill.

Good intentions were overtaken by reality, overcrowding and rather poor managerial decisions, such as the notion to leave part of the care of the asylum’s patients to the attentions of the inmates at the neighboring penitentiary. (I’ll focus more on the Roosevelt Island’s prison life next week.)

The asylum swiftly entered the public imagination. Charles Dickens, on his tour of America, visited the asylum and found “…everything had a lounging, listless, madhouse air, which was very painful. The moping idiot, cowering down with long disheveled hair; the gibbering maniac, with his hideous laugh and pointed finger; the vacant eye, the fierce wild face, the gloomy picking of the hands and lips, and munching of the nails: there they were all, without disguise, in naked ugliness and horror.”

The asylum swiftly entered the public imagination. Charles Dickens, on his tour of America, visited the asylum and found “…everything had a lounging, listless, madhouse air, which was very painful. The moping idiot, cowering down with long disheveled hair; the gibbering maniac, with his hideous laugh and pointed finger; the vacant eye, the fierce wild face, the gloomy picking of the hands and lips, and munching of the nails: there they were all, without disguise, in naked ugliness and horror.”

Part of the asylum was lost in an inferno in 1858. One can only imagine the pandemonium of evacuating mental patients without the modern medications and restraints of today. And the sounds of the blaze mixed with the shouts and howling of the patients.

It was swiftly rebuilt but the conditions were no better. Intrepid reporter Nellie Bly then steps into the story at this time, in a move that would inspire budding Geraldo Rivera’s well into the future. In 1887, already well known for evocative articles on social reform, Bly took an assignment for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World newspaper to enter the asylum disguised as a patient. (Why some actress like Charleze Theron has not played her in a film is quite beyond me.)

Bly’s reporting of conditions there are as shocking today as they are melodramatic. “From the moment I entered the insane ward on the Island, I made no attempt to keep up the assumed role of insanity. I talked and acted just as I do in ordinary life. Yet strange to say, the more sanely I talked and acted, the crazier I was thought to be by all….” Laughably misdiagnosed, Bly was tormented with rotted food, cruel nurses and cramped and diseased conditions for ten days before released with Pulitzer’s help.

Her reporting did more than shine a light on poor conditions for the mentally ill; it apparently also spelled the end of Blackwell Island’s asylum. By 1893, the patients were transferred further up the East River to Ward’s Island and the building given to more traditional medical services, becoming Metropolitan Hospital. It made the former asylum home for more than fifty years, leaving in 1955 and essentially abandoning Davis building to deteriorate.

For years the only remaining vestige of the asylum was the Octagon, with the entrance tower and once spectacular spiral staircase. Certainly it must has inspired Batman writers to create Arkham Asylum, Gotham City’s home for the mentally insane and frequent home of most of the caped crusader’s rogue gallery.

For years the only remaining vestige of the asylum was the Octagon, with the entrance tower and once spectacular spiral staircase. Certainly it must has inspired Batman writers to create Arkham Asylum, Gotham City’s home for the mentally insane and frequent home of most of the caped crusader’s rogue gallery.

Hmmm, ancient site of mental and physical horrors? I know, let’s build a condo! That’s exactly what the developers of The Octagon have done, completed last year. They have however preserved the octagonal tower and stairwell, leading me to suspect that at least they’re not hiding from the location’s wild, unsettling history, despite the promises of their website — “a Midtown venue with small-town values.” *shudders*

NEXT WEEK: More on Roosevelt Island’s peculiar and disquieting history