Our modest little series about some of the greatest, notorious, most important, even most useless, mayors of New York City. Other entrants in our mayoral survey can be found here.

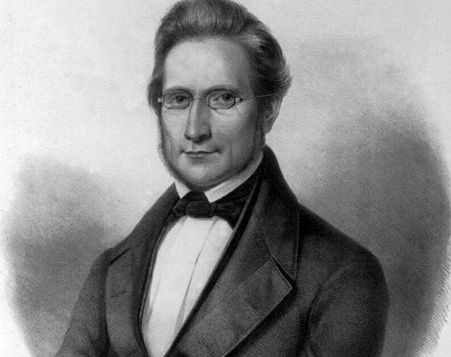

Former New York mayors are all around you. No, Ed Koch is not hiding in your closet — maybe not today — but you can find their names almost anywhere, including your local bookstore. Meet James Harper, the Harper of Harper-Collins, and mayor of New York in 1844.

I think I say this about every decade of New York history, but the 1840s was an especially tumultuous era, thanks to the aftermath of the Panic of 1837, and to the massive influx of Irish immigrants spilling into the city.

Nativism, the form of political xenophobia aimed during this period at the Irish, was rearing its head in state politics in 1841 when Governor William Seward proposed funds be set aside for a parochial private school system for Irish Catholics, who were alienated from regular schools due to the use of the King James Bible. (Separation of church and state? What’s that?)

Opponents formed the anti-immigrant American Republican party and within just a couple years had received substantial clout at the voting booth in New York. In 1844, the time was right for them to propose a mayoral candidate to serve their needs.

James Harper and his three brothers formed Harper and Brothers in 1833, from the print shop of James and his brother John. It wouldn’t be until mid-century that the small but prolific house started producing Harper’s Magazine and Harper’s Bazaar. By then Harper was a well-established and powerful publisher, printing some of New York’s best known authors, including Edgar Allen Poe, Herman Melville and Washington Irving and delivering the first American printings to such books as Charlotte Bronte’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ and Charles Dickens’ ‘Bleak House’.

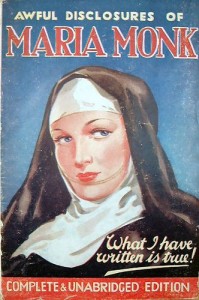

Harper was an ardent nativist, having made his publishing house’s reputation with a salacious (and apparently deranged) anti-Catholic tome by Maria Monk entitled Awful Disclosures. (At right: a 20th century reprinting of Monk’s famous ramble.)

Harper was an ardent nativist, having made his publishing house’s reputation with a salacious (and apparently deranged) anti-Catholic tome by Maria Monk entitled Awful Disclosures. (At right: a 20th century reprinting of Monk’s famous ramble.)

Nominated as a school commissioner in 1842, Harper lurched for the mayoralty two years alter, promising to reform local government of its Irish influence. He had the good fortune of running after an extremely ineffective mayor (Robert Morris) and against two conflicted and split parties (the Democrats and the Whigs). And so, in April 1844, the American Republicans had their first — and only — mayor.

An overly florid 1855 nativist creed — The Arch Bishop: or, Romanism in the United States — describes his victory:

“Mr. James Harper, the American Republican, had triumphed over his opponent who, with the whole foreign vote combined in his favor, stood rebuked and abashed before Liberty’s searching eye.”

The dream was a brief one for Harper. Irishmen on the city payroll were indeed removed, and Harper curtailed liquor sales in the city, including one very dry July 4, 1844. Under his regime, trash-eating pigs were prohibited from wandering the streets. Most notably, he went against the state legislature and formed his own municipal police force, which was abruptly abandoned the following year with the state’s reform — setting up a system of city police wards that would later to be corrupted by Tammany Hall and almost everybody else.

Harper’s whole reform ideology was undermined by an event completely out of his control. Anti-Irish sentiment had swelled in nearby Philadelphia and spilled over into violence, a three day riot resulting in several deaths, the torching of two Catholic churches and the transformation of some Protestant churches into armed fortresses. (Below: an illustration of the violence in Philadelphia.)

It appears the coalition of forces that got Harper elected crumbled under the fear of similar ramifications coming to New York. “I shan’t be caught voting a ‘Native’ ticket again in a hurry,” said George Templeton Strong in 1845, when Harper was swept aside for the newly elected William Havemeyer.

And with Harper’s power went the glue holding together the American Republican Party. Changing their name the next year to the Native American party, the anti-immigrant torch would be relit a few years later with the more successful Know-Nothing Party.

As for Harper, he returned to his publishing business, constructing an impressive empire that lives on today. (Harper merged with Collins in 1990.) Both Harper’s Magazine and Harper’s Bazaar have been in publication ever since.

Unlike many former mayors, who fade into a decidedly non-corporeal legacy, Harper still has an admirable home on Gramercy Park — 4 Gramercy Park West, to be exact — one of the most beautifully preserved buildings on the block. (See below.) He lived here a few years after stepping down as mayor until his death. And he’s buried at Greenwood Cemetery along with many other more influential mayoral luminaries.