ABOVE: Park Avenue — before the cars came

I’ve posted the extraordinary picture above of pre-1920s Park Avenue a couple times in the past, but I wanted to do so again in light of Michael Bloomberg’s recent proposal to turn Times Square and Herald Square into partial traffic-free plazas. His plan calls for “traffic lanes along Broadway from 42nd to 47th streets and from 32nd to 35th streets” to be “transformed into pedestrian lanes”, with the residual traffic flowing down a Seventh Avenue refitted for four lanes.

The notion of creating public space out of vehicular traffic areas in Manhattan flies in the face of what used to be called ‘progress’ — at least in the Fiorello Laguardia/Robert Moses definition of the word.

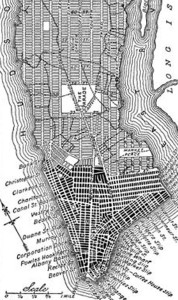

In a way, you can say this type of reversal for the benefit of pedestrians actually began in the 19th century, before the roads were paved. When the original commissioners plan of 1811 was initiated, the intention was to direct the city’s growth and organize a rational method of parcelling out the city to developers. In doing so, it sliced up Manhattan as though it were an ice tray, rows of uniform blocks in a cross-section of streets and avenues. However, there were few parks in that original plan (at right).

In a way, you can say this type of reversal for the benefit of pedestrians actually began in the 19th century, before the roads were paved. When the original commissioners plan of 1811 was initiated, the intention was to direct the city’s growth and organize a rational method of parcelling out the city to developers. In doing so, it sliced up Manhattan as though it were an ice tray, rows of uniform blocks in a cross-section of streets and avenues. However, there were few parks in that original plan (at right).

In practice, however, some virtual streets were transformed into public spaces once it seemed obvious that uninterrupted rows of development would cause for an unlivable city. Notably, Central Park was envisioned in the 1850s as a way to break up the grid. (The Parks Department actually has a nice short history on this 19th century struggle.)

Another major shift towards a pedestrian driven city occurred with the disappearance of the elevated trains and creation of the subway system, opening up darkened city streets and creating new public spaces. Additionally, as in the picture above, once Grand Central began hiding its train tracks underground, the newly created real estate above it became, you know, a park avenue.

Social activism at the turn of the century, led by Jacob Riis and others, made a play at eliminating decrepit slums in exchange for pedestrian areas. For instance, Most of Five Points was wiped from the map to become Columbus Park and various governmental buildings. Swaths of land in the Lower East Side were cleared of tenements to become open space, like the Sara Delano Roosevelt Park.

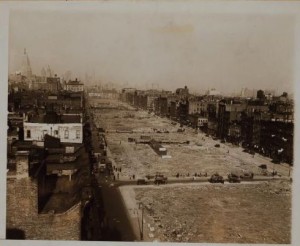

Below: In this picture from 1932, tenements between Chrystie and Forsyth have been eliminated to make way for the future Sara Delano Roosevelt Park.

Robert Moses liked his parks, but he also loved his expressways, and he created both at the expense of the neighborhoods they were supposedly to have served. But Manhattan was becoming a latticework of traffic congestion well before that; everywhere you looked, streets were widened to accomodate vehicles — first carriages and trolleys, later cars and buses.

Bloomberg’s ambitions stem from a more environmental motivation, with newly installed bike lanes, pedestrian spaces in the Meatpacking District and Madison Square, and last year’s temporary no-traffic days on Park Avenue. His midtown plans, to be installed this summer, may become permanent. Below: A rendering of his virtual Herald Square:

2 replies on “Bloomberg’s Time Square plan: a blast from the past?”

Inspect away Congestion! The city should toughen inspections for medical, psychiatric and vehicle reasons to cut down the number of congestion. This way, we will also get the voters against congestion pricing, who live in Bayside and Staten Island, to move away. Free health care means psychiatric care for all those angry talk radio white males!

I for one am a fan of Robert Moses and his vision as I love expressways, to me, they make New York what it is. Expressways, bridges and skyscrapers are still invigorating to me.