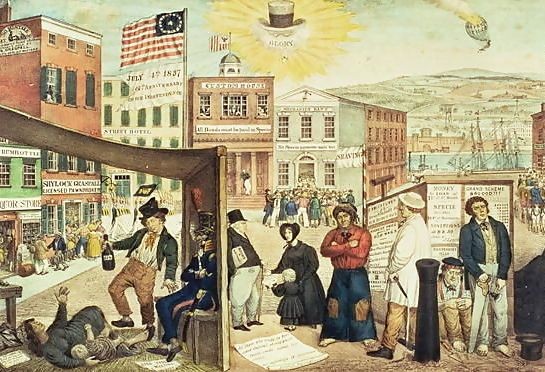

Above: New York by 1837 (in an painting by Edward Williams Clay) — a city surviving financial ups and downs, fires and water shortage, riots, cholera and the mayoralty of Cornelius W. Lawrence

KNOW YOUR MAYORS Our modest little series about some of the greatest, notorious, most important, even most useless, mayors of New York City. Other entrants in our mayoral survey can be found here.

In office: 1834-1837

We’re going back to the era of the great fire one more time to take a look at the man in charge of the city during that time — Cornelius W. Lawrence, the first elected mayor of New York.

I couldn’t find any portraits of Cornelius, but I found something better: the following description from a mid-19th century journal: “…old Cornelius had the ice cream and strawberries of everything in life — in commerce, in politics, in wives, in finances and in religion….He had a peculiar way of carrying his spectacles in his hand, behind his back while he looked at all the pretty girls he met.”

But getting to that ‘ice cream and strawberries’ required surviving one of the most tumultuous city elections — and the subsequent years of trauma — that a New York mayor has ever had to endure.

Lawrence was born in 1791 in bucolic Bay Side(in the future Queens), a farm boy with big city intentions at an early age. He became entranced with the lucrative merchant culture of New York, working his way into his own dry-goods auction house, the firm of Hicks, Lawrence & Co. with the wealthy Quaker financier Willet Hicks and Lawrence’s brother Richard. Their auction house was at Pearl and Fulton streets (just off Schermerhorn Row near the South Street Seaport today).

Lawrence, a high-profile merchant by 1832, was also a politically ambitious Democrat and served two years as a state congressmen before turning to local politics at a uniquely opportune moment.

Before 1834, the position of mayor had been appointed by the Common Council of the city, an unelected job that was shaped more by the political favoritism of governors and city alderman (who were elected) than by any particular leadership characteristic. This was finally amended by New York state in 1834, allowing for the mayor’s job to be popularly elected. And, not surprisingly, that first election was an absolute, chaotic mess.

The long-established Democrats and a surging Whig party wanted to get their hands on this now attainable position. As a result, that election day, spring 1834, came with voter intimidation, massive fraud, and angry riots which overtook the polls, particularly in the volitile Sixth Ward. The Democrats had put up Lawrence to challenge the wonderfully named Gulian Crommelin Verplanck, a colorful poet and former Democrat. When the dust settled, the Whigs were victorious in a majority of alderman posts, but the Democrat came out on top as mayor — by a mere 180 votes!

Below: New York in 1836, as per “Hooker’s new pocket plan of the city” (Click into it for a closer view)

Lawrence would be elected for three stressful one-year terms (spring 1834-spring 1837). At the very top of his to-do list was New York’s water supply. The new mayor had inherited a city quickly bursting with new residents and a paltry water supply so rancid and inadequete that one source blames it for the increase in public drunkenness. (Hey people have to drink something, right?)

Exacerbating the matter was the fear of disease. In 1832, his first year as congressman, New York was struck with a devastating cholera epidemic, killing hundreds; a lesser but no less dangerous sequel struck in 1834, just as Lawrence was getting comfortable at City Hall. And of course, the spectre of fire lurked, not just jeopardizing a highly flammable city, but Lawrence’s own fortunes: he controlled shares several fire insurance companies.

Plans for what would become the Croton aqueduct were well underwway when the Great Fire of 1835 devastated New York, destroyed the Merchant’s Exchange and potentially spelled doom for the city’s future. Lawrence himself lost thousands of dollars in shares, although his own auction house on Pearl Street had been spared.

The mayor and his entourage stormed down to Washington begging for aid for his beleagured city, to no avail. Fortunately, former mayor Philip Hone succeeded in persuading the state government to dole out millions in relief. Meanwhile, voters finally approved the construction of the aqueduct in 1836. Within the year New York experienced a burst of rapid reconstruction; the price of New York real estate post-fire soared to outlandish prices.

But fire and water weren’t Lawrence’s only distresses. Sometimes he had to fear his own constituents.

BELOW: Anti-abolitionist riots kept the city on edge during the 1830s

Pro-slavery sentiment among some New Yorkers culminated in a series of deadly riots in the 1830s, one during Lawrence’s first months as mayor, leading to the destruction of property owned by abolitionists and prominent businessmen Lewis and Arthur Tappan. Lawrence denounced the mob (after posing a threat to his wealthy friends) and ordered the National Guard to disperse them. Later, Tappen penned this mea culpa to the mayor, ensuring his good intentions, particularly the assurance that the abolitionists “will never, in any way, countenance the oppressed in vindicating their rights by resorting to physical force.”

Being a Democrat in the 1830s meant a marraige between the Jacksonian wealthy and a powerful Irish working-class, strange bed-fellows often culminating in disaster. At a New Years eve celebration at the mayor’s home in 1837, supporters stormed the doors, turning the home into a ‘Five Points tavern’ by one account. The police were summoned in an effort to clear away the mayor’s own supporters!

As if these catastrophic events hadn’t been enough, Lawrence was finally thrown out of the mayor’s seat due to the results of the greatest catastrophe of all — the Panic of 1837, a financial crisis that briefly shifted the city’s power from the Democrats to the Whigs. He was defeated by Aaron Clark, who would prove to be the only Whig mayor of the city.

Perhaps ready to move on anyway, Lawrence entered the world of banking in his later years, interuppted only by a four-year stint in a federal role under President James Polk as the Collector of Customs.

He lived his later years in the city in a home near Broadway and Worth Street, before finally retiring back to the family home in Flushing. He died in 1861 and you can conceivably still go visit him; he’s buried at the Lawrence family burying ground at 216th Street and 42nd Avenue in Bayside, Queens.

7 replies on “Mayor Cornelius Lawrence, son of Bayside”

Thanks for posting such an interesting portrait of my ancestor Cornelius buried in our family graveyard. We do have a portrait of him which will be in our upcoming Lawrence family history book. My Dad showed me photos of the revenue cutter CW Lawrence that was commissioned a few years later. It sailed around the tip of South America and patrolled the Golden Gate Harbor during the gold rush. It unfortunately ran aground in 1851 near the Cliff House. Eventually the 1984 Californian tall ship was built as an exact replica and resides in the San Diego harbor. Best regards, Robb Lawrence, author of The Les Paul Legacy.

I am a volunteer with the Bayside Historical Society. We are maintaining the Lawrence Graveyard in Bayside which is a NYC Landmark. We have an Eagle Scout working in the cemetery for his project. We need info from you. I hope you can contact me. Thanks Carol Marian

Fascinating portrait. As an amateur genealogist of the Long Island Lawrences, I found the description of my ancestor very compelling.

Robert & Stephen … if you come back to this article, please contact me at your earliest convenience: president@baysidehistorical.org. Or contact us as baysidehistorical.org. We at the Bayside Historical Society are the caretakers of the Lawrence Cemetery you speak of and would be interested in speaking with the ancestors of the Lawrence family interred there. Thank you, Paul

I have just acquired a document signed by your ancestor Cornelius W. Lawrence. It is the legal document appointing William Kehoe as “Sunday Officer” to enforce the observance of the Sabbath. It is dated Aug. 8, 1835 and is signed four times. Richard

Do you know if the anti-abolitionist image used here is a specific reference to the riots of 1834? I saw this somewhere else and was included in the draft riots of 1863. I am looking for an image of 1834 and would also like to know how to reference it. I know this was written quite a while ago but thought I would try contacting you anyway.

I dont believe that is an image depicting the riots of 1830s. Difficult to find many artistic renderings from that period. Good luck!