Four hundred years ago, on September 12, Henry Hudson sailed into New York harbor and casually discovered the island of Mannahatta, the future home of New Amsterdam, Wall Street, and the New York Yankees.

Two hundred years later, ferry mogul Robert Fulton patented the steamboat, an engineering marvel he perfected, but did not invent. Fulton, a Pennsylvanian who originally tested his ship in Paris, became associated with New York with the development of the successful Clermont North River steamboat service in 1807.

Reason to party, right?

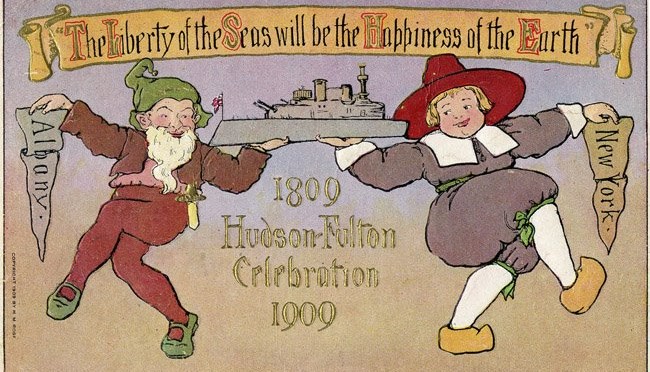

New Yorkers thought so 100 years ago, planning the official Hudson-Fulton Celebration in the fall of 1909, as a grand, showy pat on the back to America’s industrial might. A state-wide soiree, it was New York’s own unofficial world’s fair, a chance to trumpet its innovations and riches via a celebration of its history and the central role of the Hudson River.

Make no mistake: as much as this was a celebration of New York, it was also a celebration of New York’s wealthy. This was the height of the Gilded Age, after all. The original plan was forged by Theodore Roosevelt’s uncle Robert, and the planning committee included Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, former vice president Levi Morton, Macys co-owner Oscar Straus, and members of the Rockefeller and Van Rensselaer families. They were celebrating New York; by extension, they were celebrating themselves.

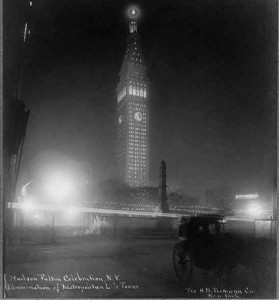

From September 25 to October 11, the river was clogged with shipping and military vessels festooned with electric lights, while overhead the skies were filled with nightly firework displays. Inaugeral nautical displays were capped with the ceremonial entry into the harbor of both Hudson’s ship the Half-Moone and Fulton’s Clermont, both re-created for the event. (The Half-Moone and Clermont unceremoniously collided into each other during the ceremony!)

Below: a postcard of the Half-Moone on its ‘revisit’ to New York harbor

On land. it was a veritable history geek’s dream, with festivals and parades devoted to New York City’s past. Each day featured a different ‘historical pageant’ in each borough, culminating in two far livelier ‘carnival pageants’, one in Manhattan on October 2, and in Brooklyn one week later.

The historical pageant would be a six-mile, papier-mache Beaux-Arts extravaganza, striding from Central Park to Washington Square Park, displaying the political correctness of the day. The parade was led by a series of floats referred to as ‘the Red Man Band’, with such dioramas as ‘the Legend of Hiawatha’ and ‘the War Dance’, escorted by members of Tammany Hall.

Dutch-themed floats depicted Jonas Bronck, Peter Minuit’s purchase of Manhattan island, and a friendly game of bowling at Bowling Green. British and Revolutionary War floats followed, featuring the death of Nathan Hale and the legend of Rip Van Winkle. Peter Stuyvesant, Alexander Hamilton, the Statue of Liberty, the Marquis de Lafayette — they were all represented.

Below: part of the Hudson-Fulton history parade, 1909

Of course, that was nothing compared to the absolutely bizarre Carnival Pageant. Rather than represent anything relating to the celebration at hand, organizers chose to, according to official history, “recall the poetry of myth, legend, allegory and in a few cases of historic fact, which, while foreign in local origin, is an heritage of universal possession and belongs to all nation.”

Bafflingly, this led to a highly flamboyant parade with such European folklore themed floats as the “Crowning of Beethoven,” “Lohengrin,” “Walkure”, “Frost King”, “Orpheus Before Pluto” and “Elves of the Spring” — almost 30 in all. A couple sample descriptions:

Frost King — “This float represented the mythical Frost King, who has control over the snows and other elements of the winter. Around him were grouped his fairies, who have charge of the winds, the snows, the frost and the thaw. The Frost King was represented in his own directing the elements.”

Elves of the Spring — “This float represented the opening of the flowers and the fairies issuing therefrom, suggesting the magical change which comes over the face of nature with the retreat of winter.”

Keep in mind that many of the myths depicted in the carnival may have been quite familiar to New York’s new populations of European immigrants. Had such a procession sprouted up on the streets today, it might be mistaken for the Halloween parade.

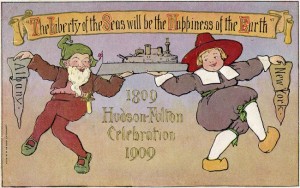

The Metropolitan Life Tower, the tallest building in New York, lights up the night sky during the 1909 Hudson-Fulton celebration

Meanwhile, mayor George McClellan Jr. and other city officials were busy elsewhere, as a flurry of monuments and plaques were dedicated that day. In fact, if you’re walking around the city and find any dedication related to the days of Dutch Manhattan, most likely it’s from the Celebration — from the marking of the old Dutch wall on Wall Street to the marker dedication to Dutch school teachers in Washington Square.

Strings of electric lights were hung from every available landmark and structure, in a sense creating the modern New York skyline that very day, as New Yorkers could now admire their city for the first time at night. Not just incidental illumination, but a decorative show that could be seen from miles away.

Thousands of lights were hung from the bridges and official buildings in all boroughs, paired with “elaborate private illuminations by the owners of large office buildings, stores and dwelling houses,” the lighted vessels in the harbor and the various pyrotechnics throughout the city to create “a veritable City of Light.”

Of course, the most well-known — and most historically significant — event from the Hudson-Fulton Celebration was Wilbur Wright’s flight from Governor’s Island circling the Statue of Liberty, the very first flight over New York waters. (Check out our podcast on LaGuardia Airport and the history of flight for more information.)

Below: Amazed New Yorkers stare as Wilbur takes a second trip through New York skies, up the Hudson River to Grant’s Tomb, then back to Governor’s Island

This year we should be celebrating Hudson, Fulton and Wright, I guess. There are celebrations planned throughout the state, and we’ll hear more about them starting in June and continuing through the fall. Manhattan has already received a new commemorative flag in honor of the event.

And naturally, we’ll be alerting you to some of these events on this blog. Maybe we’ll even have our own. Anybody got a elf costume?

By the way, the official history of the Hudson-Fulton Celebration is worth a look, especially for its descriptions of regular events.