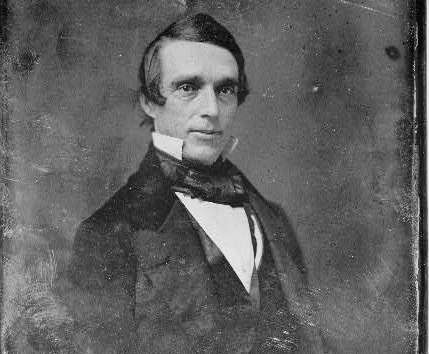

An early portrait of A. Oakey Hall as photographed by Matthew Brady

KNOW YOUR MAYORS Our modest little series about some of the greatest, notorious, most important, even most useless, mayors of New York City. Other entrants in our mayoral survey can be found here.

In office: 1869-1872

Few leaders of New York could match Abraham Oakey Hall in personal flair. For every nine colorless businessmen who ascend to the mayoralty, there is one truly debonair statesman, an enigma of charm who seems to govern with ease. In 1869 that was Hall, a jack of all trades, a raconteur and paragon of style. Unfortunately, as the most glamorous member of the notorious Tweed Ring, corruption may have been another trend that suited him.

Before the events, Hall was destined for great things. Most (even Tweed himself) assumed Hall would become New York’s governor, with the White House in sights. He was after all born in Albany, in 1826, back when New York’s capital was one of the most populous cities in the entire country. For those who believed in such things, Hall’s birth there might have been providence, because his parents were merchants in New York and were merely visiting Hall’s grandfather. “I was born transitu,” he proclaimed later. But he never made it back to Albany, at least not officially.

A slight, nimble figure, Hall expressed a variety of talents at an early age, latching on first to journalism, writing for many city newspapers while working his way through New York University, graduating in 1844. Next came a love for the law, attending both Harvard and Cambridge before heading to New Orleans to start a small practice. He then returned to Manhattan and swiftly maneuvered through the courts to become the assistant district attorney in 1850 and a short time later to even argue a case before the state Supreme Court — all before he was 25 years old.

He would win true acclaim and popularity, however, as the city’s district attorney proper, serving first from 1853-1859 and again from 1861-1869, one of New York’s most important legal voices during the Civil War. He allegedly prosecuted over 12,000 cases. He was also on hand during the Draft Riots, funneling many rioters through the court system and straight to jail. His accomplice was often judge John Hoffman, soon to be the mayor of New York who preceded Hall. Their crusades against rioters would boost both their popularity.

Hall would also be known for a rather alarming law briefly on the books in 1855. The state had outlawed the sale of alcohol in the entire state. Under advisement of mayor Fernando Wood (who wanted to please hard-drinking Irish voters), Hall constructed a law allowing for unencumbered liquor sales, seven days a week, in the two months before the prohibition was to take effect. May and June of 1855 were the booziest months in New York City history.

Above: City Hall in 1874 in an illustration by Currier and Ives

With his professorial good looks and humorous demeanor, A. Oakey was a natural for politics of course. Bespeckled and bearded, he spoke elegantly — Elegant Oakey was his nickname after all — and wrote passionately. He penned social polemics, theatrical plays, political tirades and at least one holiday novel — Old Whitey’s Christmas Trot.

More importantly though, he was an attractive politician to Tammany Hall and in particular its boss, William M. Tweed**.

We know the Tweed Ring as that most notorious of crooked entities that came from the Democratic machine. In fact, through, Hall was for many years a Republican — even claiming to have helped form the Republican Party! — and was even elected District Attorney as a member of that party. But he was lured into Tammany Hall shortly before the war ended and would facilitate their dominance over the affairs of City Hall.

‘Boss’ Tweed liked him because he was confident, likable, distracting. He often quoted Shakespeare and cracked jokes. The complicated layers of graft, bribery and outright theft that were installed in city government needed an attractive front. In one of the most manipulated elections in New York history, Tweed and Tammany Hall succeeded that fall of 1868 in getting their man Hoffman into the governors seat, with Elegant Hall becoming his elegant replacement at City Hall. (Hall would be re-elected three times in heavily tampered elections.)

The year 1869 was a watershed year in New York City corruption, with the Tweed’s hand-selected cohorts fully in place at City Hall, all oversight committees abolished the previous year, and civic projects sprouting up throughout the city, ripe for graft and embezzlement.

Tweed and the others directly associated with the ring (chamberlain Peter Sweeny, comptroller Richard Connelly) needed Hall’s charm to bedazzle the press and public, deflecting any charges of malfeasance.

The level of Hall’s involvement in the city corruption at the time is unclear. He was brought before a grand jury twice, once during the final days of his tenure as mayor. Two trials followed, the first ending in mistrial, the second in acquittal. Despite clear signatures on dozens of suspicious invoices, Hall claim was that he was much too busy running the city to have carefully inspected each and other claim.

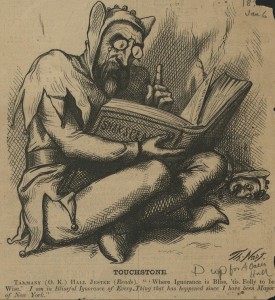

Below: Thomas Nast parodies Hall’s statements at being ‘blissfully ignorant’ of corruption

Perhaps so. During his first year in office came a devastating stock market crash, the Black Friday of September 24, 1869, facilitated by Tweed’s chums Jay Gould and Jim Fisk.

As immigrant numbers increased — as tenements like Five Points were swelling to overcrowded — racial and religious disunion threatened the city. Like Tammany, Hall was a friend of the Irish; on St. Patricks Day, he would wear an emerald flytail coat. When Hall suddenly banned the particularly violent protestant Orange parade that year, its participants feared his actions were controlled by Irish Catholics. Governor Hoffman ordered the parade to resume, but the result was an even more violent riot, with 62 people dead and over a hundred injured. Confidence in Hall’s leadership quickly evaporated.

As immigrant numbers increased — as tenements like Five Points were swelling to overcrowded — racial and religious disunion threatened the city. Like Tammany, Hall was a friend of the Irish; on St. Patricks Day, he would wear an emerald flytail coat. When Hall suddenly banned the particularly violent protestant Orange parade that year, its participants feared his actions were controlled by Irish Catholics. Governor Hoffman ordered the parade to resume, but the result was an even more violent riot, with 62 people dead and over a hundred injured. Confidence in Hall’s leadership quickly evaporated.

Despite the aura of corruption and mediocrity that hung over his tenure as mayor, Hall actually had a quite colorful life afterwords, working as both a newspaper editor (for the New York World), a London correspondent for the New York Herald and the manager of a theater. He even produced and starred in his own play. For some reason, few went to see it.

He returned to practicing law in his later years in London, famously returning to New York in a court case in 1893 representing Emma Goldman. Despite the convergence and press coverage of these two great New York figures, Goldman and Hall lost the case.

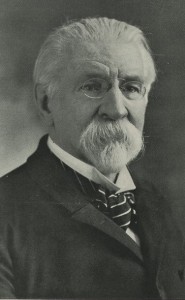

Hall died on October 7, 1898, at his home at 68 Washington Square South, just blocks from where he first went to college. The picture above was taken the year of his death (pic courtesy NYPL)

**Wanna know more about Boss Tweed and the Tweed Ring? Tune in on Friday!